|

Tamil Culture and Language in

South Africa

Mathavakrishnan Mudeliar

(Kajan)

(formerly of South Africa, an active member

of the Tamil community in Sydney. member of the

Australian Tamil Federation)

Courtesy

Tamil Federation of KwaZulu Natal

The indentured Indians arrived in South Africa in

1860 onwards from all parts of southern and eastern

India and various factors motivated them. For most

it was a case of escaping from conditions of

extreme poverty and its resultant misery and

disease, while others were spurred by ambition or a

sense of adventure. Coming as they did from all

parts of India different languages and cultures

were present among the immigrants. There were a few

Christians and a small number of Muslims, but the

majority were Hindus belonging to different caste

systems.

The indentured or immigrant Indians were followed

by other groups known as passenger Indians ( as

they paid their own passage ) mainly to live and

conduct their commercial activities. The majority

of passenger Indians were Muslims and spoke

Gujerati and Urdu, while the indentured Indians

spoke Tamil, Telegu and Hindi. Some of the

Gujerati- speaking passenger Indians was of the

Hindu faith.

The descendants of indentured workers in the

sugarcane fields of Natal and of the passenger

Indians are now part of South Africa's

heterogeneous population. Until the beginning of

the twentieth century it was still necessary, for

obvious reasons, to differentiate between passenger

and indentured Indians. But the remarkable progress

of the community as a whole in economic and

educational spheres has made this differentiation

unnecessary and in 1963 the Government was able to

introduce legislation that placed all Indians in

South Africa on an equal footing.

The Indian immigrants brought with them to South

Africa the heritage of an ancient caste system.

Each caste was a distinct, exclusive social entity

that bound a member from birth to death. The caste

system was characterised by a strict hierarchy and

contact between the different castes brought

unforgivable disgrace. That those on the lower

rungs of the hierarchy emigrated as indentured

labourers is understandable; that any one of

elevated position should choose to do so, despite

this involving social contact with those of low

caste, even sharing amenities, is remarkable and

indicates how compelling the economic and other

factors were. It also reflects a degree of

adaptability, particularly when seen in the

traditional Indian context.

The adaptability, the capacity to accept the

realities of life, is characteristic of South

African Indians. They found that the caste system

did not work in south Africa and from the beginning

adapted themselves to the differing circumstances.

A few isolated attempts were made to institute a

village caste system, but these were soon abandoned

when the young people left for urban areas to seek

employment and were influenced by Western cultural

and economic concepts. Now-a-days the caste system

is virtually non-existent with the exception of a

few Hindu communities that continue to practise

endogamy.

It is reasonable to assume that the Indians,

because they rejected the caste system in favour of

a Western way of life, would also tend to reject

their faith. But this is not so. The Hindu religion

has more than 75% of the Indians as adherents,

while the remainder, more than 20% are of the

Islamic faith and the rest Christians and other

faiths, the Indian community has thus retained its

essentially Oriental character in many vital

respects, despite western cultural influences.

Many Indians speak English as it enables them to

overcome language barriers in their business

dealings with those who speak other Indian

languages and with members of the other national

groups. English has in fact also become the

language of social communication within the Indian

community and many young Indians hardly speak their

mother tongue at all. English also dominates the

field of education, so that were not for the

efforts of certain cultural groups, the survival of

the Indian languages would be jeapardised. However,

the Indians in South Africa have always been able

to retain vital contact with the age-old traditions

and customs of their own culture.The Indians are a

compassionate people and they are always ready to

make financial sacrifices. This is part of their

cultural and religious background. With sanguine

enthusiasm and robust faith the early Indians taxed

their own scanty means to promote and nurture the

Tamil culture and language not only for their

children but also for the generations to follow.

The majority of the Indian immigrants of the

nineteenth century arrived in South Africa with

little else but the clothes they wore. Today,

because of the economic opportunities open to them,

their position is in no way comparable with that of

their forebears or of their compatriots in other

countries. Well -paid respectable positions have

been open to all and many have their own commercial

enterprises, while several have become

millionaires. In addition to the continued general

support given by the Indian community the Indian

commercial community has been generous and

donations from Indian trading enterprises assist

the cultural, religious and educational progress of

the community. Individual traders and commercial

enterprises also make contributions towards

erecting and maintaining mosques, temples and

schools.

In order to propagate the language they started

Tamil schools in their homes by gathering a few

children together in the evening. The only reader

in use in the early days was the " Aritchuvadi "

which was used from the beginning to the end, and

whoever completed the whole reader with success was

regarded as reasonably learned in Tamil. With the

establishment of various organisations in different

parts of the country , Tamil schools were

established on modern lines. New readers graded

from 1 to 6 were imported from India.

It must be noted that nearly all the Tamils of the

early period spoke only Tamil and hardly knew

English. As a source of communication and t give

news about the country adopted, as well as India

the first Tamil newspaper - VIVEKA BANU - was

introduced. The Tamils read this with avid

interest. This came to an end when the principal

editor went back to India. The 1930's saw the

appearance of another Tamil newspaper - SENTHAMIL

SELVAN - that satisfied the desire of the Tamils

for news in their own language. Several other

publications followed but they were short-lived for

want of material support. The Tamil immigrants

pursued, in a modest form, aspects, of their

culture, at the same time exposing their children

to them. They spoke their mother tongue within the

confines of the barracks compound and outside and

worshipped their chosen Deity at their simple make

- shift temples. Some of the children were

fortunate enough to receive the rudiments of Tamil

from educated elders who may be counted among the

many unsung personalities of early Tamil education.

In spite of steady progress being maintained, Tamil

leaders began to express concern about the future

of Tamil education, because they feared that, as a

strong priority was given to English education and

there was motivation for it, the promotion of Tamil

education would be neglected. More Tamil leaders

emerged to promote Tamil culture vigorously.

To sustain interest and to keep the language alive,

organisations like the Natal Tamil Vedic Society

have established Eisteddfod committees which

organise elocution, drama and music on a

competitive basis for the pupils attending Tamil

schools, especially in the small towns and

suburbs.

Whilst the spoken language has suffered from

environmental changes, other features of Tamil

culture have remained intact up to the present day.

A number of factors helped in this direction. In

recent years religious organisations and cultural

bodies, upon providing a well-motivated request,

may receive government funding for the promotion of

culture. Cultural bodies with meaningful names

created for the training and promotion of music and

the arts are to be found throughout South Africa

where Tamils live in appreciable numbers. Special

functions are organised for the presentation of

modern music or Katcheri (classical music and song

recitals). A number of dance schools have been

opened at which training is given by tutors who

made a special study of the art in India.

An important aspect of the Tamils social life in

South Africa revolves around the observance of

cultural traditions, which include weddings,

funeral rites, amongst others the various

festivals, and poojays such as the Adi and

Puratassi months. Tamil weddings are well organised

and conducted timeously amidst music appropriate to

the occasion. At any of these weddings, one would

see a colourful spectacle of South Indian women

gracefully attired in saris, approved by their

culture.

Hindu women in South Africa, like their

counterparts in South India, represent a resilient

aspect of Tamil life, as it is she who makes up the

home. In every Tamil home religion is a dominant

idiom as it is with the other sections of the Hindu

community. A room or part of it is set aside for

daily worship before a sacred lamp and she is in

complete charge of it.

South Africa is presently undergoing a new order

where the different races are coming in close

contact with one another, learning together and

working together and all this would be expected to

change the lifestyle of every South African

citizen. In spite of the acculturation that is

taking place, important features of ethnic cultures

would continue to be promoted. Indian culture in

general and that of the Tamils in particular, which

is of great antiquity, possesses a lasting richness

in human values and the spirit - elevating features

of culture brought to South Africa by the Indian

immigrants continue to be pursued, promoted and

nurtured.

Wherever Indians settled, their approach was one of

selecting, synthesizing and harmonising with the

best in all fields of thinking and endeavour. This

involved the synthesizing and harmonising of old

ways and new: orthodox and unorthodox; sacred and

secular; religion, science and mysticism; and most

importantly, the synthesizing of western, eastern

and indigenous cultures and traditions. Yet in all

these cross-cultural exchanges, their roots

remained and weathered many storms and continue to

do so.

References:

1. Fiat Lux, Durban vol 2 1988

2.Kuppusami C,Tamil culture in South Africa.

3.Natal Tamil Vedic Society- Souvenir Brochure

4.The Department of Information, Pretoria: The

Indian South African.

5.The South African Tamil Federation - 25th

Anniversary Brochure

|

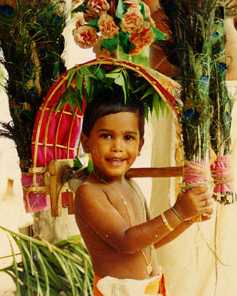

Kavadi in the South African Cult

of Murukan - Dr. Sarres Padayachee (abstract

of paper presented at the Third Murukan Conference, Kuala

Lumpur 2-5 November 2003) Kavadi in the South African Cult

of Murukan - Dr. Sarres Padayachee (abstract

of paper presented at the Third Murukan Conference, Kuala

Lumpur 2-5 November 2003)

The

indentured Indians who left India, the cradle of

Hindu culture and mother of Hindu tradition,

arrived in South Africa during the second half of

the 19th Century. They brought with them a

historic culture which was distinct from the

dominant Western and indigenous black cultures in

modes of worship and philosophy. Thus were the

seeds of Hindu religio-cultural expression, which

embraced a plethora of oral traditions, rituals

and festivals, transplanted into a fecund African

and colonial environment. The

indentured Indians who left India, the cradle of

Hindu culture and mother of Hindu tradition,

arrived in South Africa during the second half of

the 19th Century. They brought with them a

historic culture which was distinct from the

dominant Western and indigenous black cultures in

modes of worship and philosophy. Thus were the

seeds of Hindu religio-cultural expression, which

embraced a plethora of oral traditions, rituals

and festivals, transplanted into a fecund African

and colonial environment.

Despite their lack of literacy and schooling, the

influences of Western and other cultures, the

strictures and obstructions of the colonial and

apartheid eras, and a profusion of

socio-political and economic difficulties, these

custodians of Hindu culture have retained their

identity. These pioneers could not have imagined

how their simple wood and iron temples would

mushroom into major religious monuments

symbolizing ultimate enlightenment.

Their committed perseverance gave rise to the

birth of many Murugan temples which today stand

as beacons of Hindu culture catering for the

religious needs of the Murugan worshippers in the

Kwa Zulu-Natal, Gauteng and Cape Provinces of

South Africa. Amongst the many Murugan Temples in

South Africa, the Sri Siva Soobramaniar Temple in

Brake Village, Tongaat, and the Shree Siva

Subramaniar Temple in Melrose truly enjoy the

status of "pilgrim centres" where devotees

assemble to pay homage to Lord Muruga.

Today, 142 years later, the unbroken continuity

of the Murugan cult in South Africa has become an

important component of popular Hinduism. This is

evidenced when a vast assembly of Murugan

worshippers from all walks of life gather to pay

obeisance to Lord Muruga and fulfill their vows

during the Tai Pucam, Sithiraa Paruvam and

Punkuni Uttiram Kavadi festivals. The growing

popularity of the Kavadi festivals also attracts

observers from other ethnic milieus in a

multi-cultural South Africa, including devotees

from the black community. Devotees ascribe the

growth of kavadi to the benefits that the kavadi

bearer experiences in the form of better health,

which many call a "new life", spiritual

attainment and material prosperity.

This paper will investigate the Murugan cult in

South Africa with special emphasis on the kavadi

ritual as practiced at two historic temples viz.

The Panguni Uththiram Kavady Festival as

practised at the Sri Siva Soobramaniar Temple in

Brake Village, Tongaat, KwaZulu-Natal and the Tai

Pucam Kavady Festival as practised at the Shree

Siva Subramaniar Temple in Melrose, Gauteng. In

this context the pre-Kavady rituals, the main

kavadi festival and the post-kavadi rituals will

be dealt with. The paper will also include a

brief synopsis of Skanda Sasthi as well as other

Murugan cult practices not undertaken at the

above-mentioned temples. The presentation will

include visual information on the important

Murugan shrines found in South Africa. A

documentary video-recording of the kavadi

festival and its component rituals as practiced

at Brake Village will form part of the

presentation.

|