|

It is now generally accepted that the conduct of modern warfare

is not only about troops, weapons, generals and battlefields - it is

also about perceptions. The manner in which a war is perceived by

states and their populations today can have a strategic impact on

its conduct. Real time images of a battlefield, flashed round the

world can shape strategic decisions about the war and the mindset

of one's strategic allies.

For many years, the role of media as an indispensable component of

modern war making has been conceptualized and discussed in military

journals and symposia as the "CNN effect".

Analyses in LTTE journals and the tenor and content of discussions

that Pirapaharan has had with some foreign media consultants in

recent years clearly indicate that the Tigers have been making an

extensive study of the "CNN effect".

The result is the

National Television of Thamil Eelam (NTT). It is

not my intention here to relate in spine tingling detail the

succulent secrets of how the Tigers set up the satellite channel in

the Vanni.

All I want to do here is to describe briefly the kind of thinking

that appears to have gone into the making of the NTT. The result is the

National Television of Thamil Eelam (NTT). It is

not my intention here to relate in spine tingling detail the

succulent secrets of how the Tigers set up the satellite channel in

the Vanni.

All I want to do here is to describe briefly the kind of thinking

that appears to have gone into the making of the NTT.

The LTTE's satellite TV has introduced a new strategic dimension to

Sri Lanka's ethnic divide. The Tigers never had the ability in the

past to give their side of the story in real time. Press releases

from London and news broadcasts painstakingly monitored and

translated from the Voice of Tigers in Vavuniya were always late or

missed the issue at hand.

Now the LTTE has the ability to transmit moving images, which are

the most effective way to get their message across. The NTT would be

the new strategic dimension in another Eelam War.

Therefore an overview of "

CNN effect" as a "strategic enabler in

modern military discourse" would set the stage for understanding what

the LTTE has got in store for our generals who got used to thinking

of war only in terms of more weapons, more troops and more foreign

assistance.

The following excerpt from an article in the US War College Journal

Parameters about the CNN Effect gives an idea of the issues it has

raised among military thinkers.

"The process by which war-fighters assemble information, analyze it,

make decisions, and direct their units has challenged commanders

since the beginning of warfare. Starting with the Vietnam War,they

faced a new challenge-commanding their units before a television

camera. Today, commanders at all levels can count on operating

"24/7" (twenty four hours a day and seven days a week) on a global

stage before a live camera that never blinks. This changed

environment has a profound effect on how strategic leaders make

their decisions and how war-fighters direct their commands".

"The impact of this kind of media coverage has been dubbed ‘the CNN

effect,’ referring to the widely available round-the-clock

broadcasts of the Cable News Network. The term was born in

controversy. In 1992 President Bush's decision to place troops in

Somalia after viewing media coverage of starving refugees was

sharply questioned. Were American interests really at stake? Was CNN

deciding where the military goes next?

"Less than a year later, President Clinton's decision to withdraw US

troops after scenes were televised of a dead American serviceman

being dragged through the streets of Mogadishu seemed to confirm the

power of CNN. Today, with the proliferation of 24/7 news networks,

the impact of CNN alone may have diminished,but the collective

presence of round-the-clock news coverage has continued to grow. In

this article, the term ‘the CNN effect’ represents the collective

impact of all real-time news coverage-indeed, that is what the term

has come to mean generally. The advent of real-time news coverage

has led to immediate public awareness and scrutiny of strategic

decisions and military operations as they unfold. Is this a net gain

or loss for strategic leaders and war-fighters?" (The CNN Effect:

Strategic Enabler or Operational Risk? -by Margret H. Belknap,

Parameters, Autumn 2002)

Former US Defence Secretary James Schlesinger has argued that in the

post-Cold War era the United States has come to make foreign policy

in response to "impulse and image."

"In this age image means television, and policies seem increasingly

subject, especially in democracies, to the images flickering across

the television screen", he said.

A commonly-cited example is the Clinton administration's response to

the mortar attack on a Sarajevo market in February 1994 that killed

sixty-eight people.

However, there are people who say that the CNN effect is no longer

an issue. James Hoge, Jr., editor of Foreign Affairs, for example,

argues that while a CNN effect of some sort may have once existed

immediately following the end of the Cold War, it no longer does,or

at least not to the same extent.

One of the potential effects of global, real-time media is the

shortening of response time for decision making. Decisions are made

in haste, sometimes dangerously so. Policymakers "decry the absence

of quiet time to deliberate choices, reach private agreements, and

mold the public's understanding."

"Instantaneous reporting of events," remarks State Department

Spokesperson Nicholas Burns, "often demands instant analysis by

governments . . . In our day, as events unfold half a world away, it

is not unusual for CNN State Department correspondent Steve Hurst to

ask me for a reaction before we've had a chance to receive a more

detailed report from our embassy and consider carefully our

options."

It has been argued quite plausibly that the CNN effect has been used

selectively by the US to create favourable diplomatic conditions for

intervening in countries in which it has strategic interests.

For example in 1993, when approximately 50,000 people were killed in

political fighting between Hutus and Tutsis in Burundi, American

broadcast television networks ignored the story. When regional

leaders met in Dar es Salam in April 1994 in an attempt to reach a

regional peace accord, only CNN mentioned the meeting. Afghanistan

and the Sudan have more people at risk than Bosnia, but together

they received only 12 percent of the total media coverage devoted to

Bosnia alone.

Tajikistan, with one million people at risk, has a little over one

percent of the media coverage devoted to Bosnia alone. Put another

way, of all news stories between January 1995 and May 1996

concerning the thirteen worst humanitarian crises in the

world-affecting nearly 30 million people, nearly half were devoted to

the plight of the 3.7 million people of Bosnia.

Basically the CNN effect created the politically favourable

international climate for the US to set up its largest military base

in Eastern Europe. But ofcourse very few have seen images of vast

Camp Bondsteel in Kosovo that sits a stride several vital pipeline

routes.

The CNN effect is also useful in achieving strategic and tactical

deterrence. "Global media are often important and valuable assets to

the US military, particularly when time is short and conditions are

critical. Admiral Kendell Pease, Chief of Information for the United

States Navy, has called global media in such circumstances a "force

multiplier." After showing a CNN video clip of carrier-based U.S.

fighter-bombers taking off on a practice bombing run against an

implied Iraqi target during Desert Shield, Pease explained that the

Navy had arranged for a CNN crew to be aboard the carrier to film

the "hardware in use" and to "send a message to Saddam Hussein."

The US expected that the images would deter the Iraqis, dent their

morale.

The US Navy realized and counted on the fact that the Iraqis

monitored CNN.

"The same thing is going on now," said Admiral Pease in Taiwan.

Prior to Taiwan's March 1996 elections, which China opposed and

threatened to stop with military force if necessary, the Clinton

administration sent two aircraft carrier groups to the seas off

Taiwan. Television crews accompanying the US Navy ships sent pictures

of the American defenders to the Chinese and the rest of the world.

By using media as a "force multiplier" in conjunction with deterrent

force, U.S. policy makers are, in effect, attempting to create a "CNN

effect" in the policymaking of a potential or actual

adversary. "Global, real-time media should not be regarded solely as

an impediment or obstacle to policy makers. It may just as well be

an asset", says a perceptive study of the subject (Clarifying the

CNN Effect: An Examination of Media Effects According to Type of

Military Intervention by Steven Livingston - Harvard University

Public Policy Papers 1997)

I hope this provides a brief theoretical background for

understanding the future of the 'NTT Effect' in Sri Lanka's evolving

strategic equation.

|

|

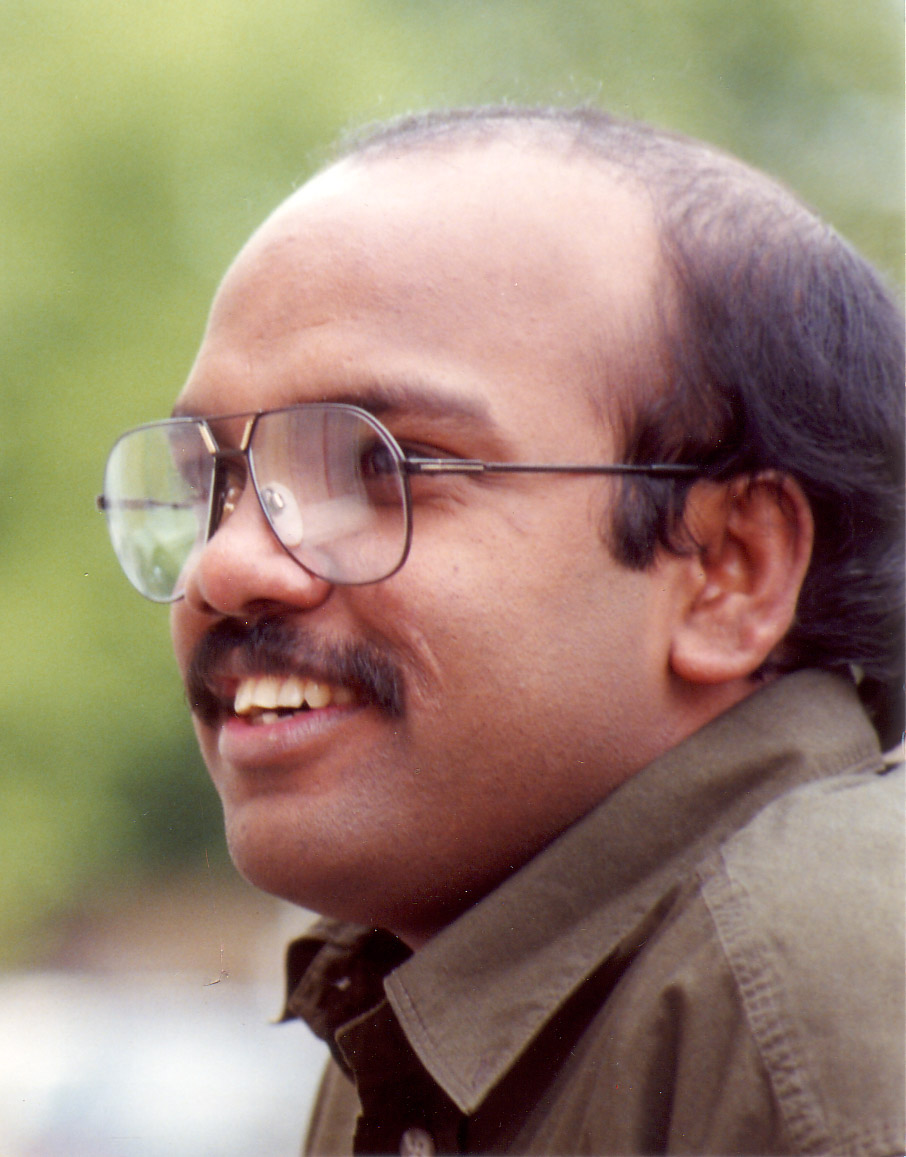

Gajaani: The Tiger's Fighter Journalist -

"My dream is Tamil Eelam"

Courtesy

Tehelka, 14 October 2006

Gajaani: The Tiger's Fighter Journalist -

"My dream is Tamil Eelam"

Courtesy

Tehelka, 14 October 2006

[see also Comments

by

K.Puvana Chandran from United Kingdom

together with response by

tamilnation.org]

A mesmerising story of innocence and brutality. Gajaani became an

LTTE member at 19, and has spent the last 13 years as one of its

official war photographers. Scorching in its simplicity, her highly

unusual account tracks the making of a soldier

I grew up in the 1970s in Kilinochchi, Sri Lanka, where I was born.

Kilinochchi was a remote area then, a place with a small population and very

poor infrastructure. My parents talk of it as a peaceful time, but the problems

in my country were already beginning.

During the riots in 1983, we

had relatives in Colombo who were taken in by Sinhalese friends. But a mob

stormed the house where they were hiding — six of my family members were killed

that day.

We in Kilinochchi were sheltered from such atrocities then. Kilinochchi was one

hundred percent Tamil; there were some military camps around, but there were no

riots. We would all listen to the radio and the elders would talk about the

stories coming through. I remember my family crying and being very upset through

these times. The stories were horrific, but I couldn’t understand or relate to

what was going on. I was just a child.

At that time, the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

(LTTE) were still very young. I remember their fighters coming to my house. Like

many families in Kilinochchi, we would help them as best we could, my Amma would

dress their wounds, we would look after them like they were our own family. They

seemed like such big people, they would tell me and my siblings about the

fighting, what it was about, what the problems were with the country and why the

Sinhalese were treating us Tamils like this. I remember hearing stories from the

riots when babies were put in boiling tar and women had their breasts cut off

and the symbol of ‘Sri’ branded in the wound where their breasts had been. Those

awful days made us mad with fear and confusion. We were sheltered in Kilinochchi,

but we were very aware of events in Sri Lanka and the grief they were creating.

In 1984, the military started an operation to wipe out the LTTE. The military

had many weapons and the LTTE had small arms, nothing sophisticated, but they

were quick and clever and knew the jungle well. Within a few days there were

dead military bodies all over Kilinochchi — they tried to kill the LTTE, but the

LTTE finished them. From this moment, we knew that we could take them on, that

they were weak and we were strong, clever and strong.

Through 1984 to ’85, Tamil people were being displaced from Jaffna, Mannar,

Trincomalee and other places, and were coming to Kilinochchi. We made space for

them in our schools, and I used to talk with them a lot and help distribute food

and blankets. I met many children my own age in these camps and they would be

really scared and upset; they had seen many horrific things and they told me

their stories. In the camps there were many LTTE fighters too. They would talk

about Prabhakaran.

I didn’t really understand why he was such a hero but, like many of my friends,

I was completely enamoured of him. I used to ask the fighters if they had ever

seen him and most would reply that they had not but they fully believed in what

he was doing and the way he led them. He was 16 when he started fighting, just

16. I was nearly that age, and I wondered what made him so special and so brave.

So I too tried to join the LTTE at age 16 — why not, I thought. But the fighters

kept telling me I was too young.

After a while, the LTTE came into Kilinochchi. They had only been in the jungle

before this, but now they began to set up bases in the town. My friends and I

were very excited; we made plans for joining a base, and finally managed to

enter one. It was a hard day; from morning to evening, LTTE cadres talked to us,

mocking us, telling us we were too small, too weak, testing our resolve. I

remember telling them that if they could do it, I could too and that I wasn’t

scared by them or their discipline.

By evening, our families were very worried and came in search of us. We

all hid and begged the cadres not to tell our families we were there. We

could see our parents talking to the cadres; their eyes were full of tears,

and we too were crying; our hearts felt we had lost something. But, at the

same time, we felt we were about to achieve something better. At one point,

our parents came near the room we were hiding in; if they had looked through

the window, they would have seen us. We crouched low and stayed very still,

we were completely silent. In that moment, I realised that my life had

completely changed. We have a saying in Tamil: பெத்தமனம்

பித்து ; பிள்ளை மனம் கல்லு - peththamanam piththu, pillaimanam kallu.

It means: the parents’ hearts are soft, but the children’s hearts are like

stone. I thought of this saying as our families finally went away.

The next night, we heard the sounds of shelling and shooting very close to

us. My friends and I were rounded up by the cadres; they were frantic, running

about, preparing everything very quickly. Someone told us the second Eelam war

had started. Two vehicles arrived at the base; my friends and I got in one and

the cadres got in the other. One cadre told us that they were off to attack the

Kilinochchi military camp and that we were being taken to a base for our

training. I can still recall her face, she was ready for battle, she was hard

and focused. It was the first time I had seen that face, but I have seen it and

worn it many times since.

We arrived that night at a base in the jungle. I had never stayed in the jungle

before; I kept waking up through the night with the strange sounds around me. As

dawn broke, I looked about. I saw the cadres sleeping nearby. I also saw many

tomb stones and realised we were in an LTTE martyrs’ graveyard. I froze. I had

gone to sleep a civilian and had woken up in the LTTE graveyard a cadre. It was

like a rebirth. I was 19.

The base became a second school to me. There were many new friends to meet,

people from all over the country, so many different faces and stories, people

with the different accents of my Tamil language. Our leaders became like our

parents. They treated us very well, and helped and encouraged us to succeed. The

training itself was very hard. I was not used to so much exercise, and we had to

learn to become strong and prepare ourselves for battle. It was hard and heavy

work. I remember crying with pain and exhaustion, but our leaders would say that

the boys could do it, so we girls had to as well — and then our determination

would make us succeed. The base became a second school to me. There were many new friends to meet,

people from all over the country, so many different faces and stories, people

with the different accents of my Tamil language. Our leaders became like our

parents. They treated us very well, and helped and encouraged us to succeed. The

training itself was very hard. I was not used to so much exercise, and we had to

learn to become strong and prepare ourselves for battle. It was hard and heavy

work. I remember crying with pain and exhaustion, but our leaders would say that

the boys could do it, so we girls had to as well — and then our determination

would make us succeed.

We would also do drama and painting workshops and, as we were the juniors, we

had to cook too. I had never cooked in my life, but here we sometimes had to

cook for 700 people. I remember one night the leaders came to the kitchen with a

goat and asked us to prepare a mutton curry. We had never handled dead animals

before; we did not even know how to skin it. So we hung the goat from the

ceiling and one at a time jumped and hung onto its cut parts to rip the skin

off. It was difficult but we had great fun.

After our training, we were divided into groups. I was the leader for one of

them. My first posting was the Palaly Front Defence Line in Jaffna. We were to

block the military from moving forward.

The first battle was very difficult. I was used to the sound of guns and bombs

and I had no fear for myself, but when a fellow cadre is killed, it is a

terrible moment. These were girls that I had known and been through so much

with, and then suddenly they were gone and I was left alone on the battlefield.

I cannot really describe the feeling very well — we have a Tamil word, urayinthu.

It means to freeze with emotion. At these moments, I had to recover very quickly

as I still had a job to do and needed to get focused. Afterwards, I would always

fight much harder, I just wanted to fight and fight and fight.

I participated in many battles in my first couple of years with the LTTE. All

through this time, I still had such a desire to meet Prabhakaran. In the middle

of a battle, I would sometimes think, ‘How can I die before meeting our national

leader,’ for this is why I was fighting, for him and our people.

I

remember in earlier times, before I joined the LTTE, I would ask the fighters I

met how they could be in the LTTE without meeting Prabhakaran. I had now been in

battles for one-and-a-half years, and I still hadn’t met him. Then came 1991; I

was being trained for Aniyiravu (the Battle of Elephant Pass), and

Prabhakaran came to the base. As soon as I

met him, I felt ready to go to battle and die for my people. I was so happy that

no matter what happened from then on, I had met Prabhakaran. My aspiration in

life had been fulfilled. I

remember in earlier times, before I joined the LTTE, I would ask the fighters I

met how they could be in the LTTE without meeting Prabhakaran. I had now been in

battles for one-and-a-half years, and I still hadn’t met him. Then came 1991; I

was being trained for Aniyiravu (the Battle of Elephant Pass), and

Prabhakaran came to the base. As soon as I

met him, I felt ready to go to battle and die for my people. I was so happy that

no matter what happened from then on, I had met Prabhakaran. My aspiration in

life had been fulfilled.

He was there on the morning of the battle, sending us off into war. We fought so

hard that day because of this. It was the most unforgettable day of my life. I

was 20 years old and the battle was called Akaya Kadal Veli Samar (the

Sky-Sea-Ground Battle). Elephant Pass is a very difficult place to fight, and

the Sri Lankan Army had planes, boats and ground troops; we just had ground

troops and had to defend and attack against all types of weaponry.

I was injured in the Elephant Pass Battle and was taken to the LTTE medical wing

for treatment. I was there for three months. During this time, the LTTE began to

develop its Media Wing and Prabhakaran asked leaders to find cadres to join it.

The leaders of my team put my name on the list, but I was not interested in

photography then — I was just focused on being a fighter. However, I finally

agreed. I arrived for my first lesson just as the class was taking their first

practice with a camera. I was handed the one camera we had at that time, and was

told about the focus. I took the camera and twisted the focus from left to

right, unaware that it is a very delicate and sensitive manoeuvre. It was the

first time I had handled a camera, I didn’t know what I was doing but I enjoyed

it.

I was asked to take a picture. I felt shy as I didn’t know what to do. Behind

me, there were many other cadres waiting their turn. Then I gently applied the

shutter button, and the camera took the picture. When the photos were printed,

mine were not so good — the exposures were all right but everything was out of

focus! But, after a few weeks, when we had an examination, I got the highest

mark in the group. I even got a prize — a camera of my own.

After this, I could not stop taking pictures. The year was 1993. I remember the

most important picture I took. I went to visit an Internally Displaced Persons’

(IDP) camp; outside a hut, a small child was eating raw fish and there were

flies and blood all over his face and body. I think this was the first time I

had been exposed to extreme poverty. Kilinochchi is not an affluent place but

these IDPs were so poor, they didn’t have anything. The sight really upset me. I

began to think about poverty, what it was about, how this situation happened to

people and, most importantly, what I could do to change it.

I took a photograph of this child and sent the image to Prabhakaran. I asked for

his opinion of what I was seeing and photographing. He was very pleased and said

that Tamil people and the world needed to see such things.

The

two greatest influences in my life have been Prabhakaran and

Col Kittu, a photographer and artist based

in London. He would send us photographic assignments and give me so much

encouragement that it was a joy taking pictures of things he asked for. Due to

the security situation, it was very difficult for me to send the pictures to

him, so I would send them to Prabhakaran. He would choose the good ones and

would send back advice and comments. The

two greatest influences in my life have been Prabhakaran and

Col Kittu, a photographer and artist based

in London. He would send us photographic assignments and give me so much

encouragement that it was a joy taking pictures of things he asked for. Due to

the security situation, it was very difficult for me to send the pictures to

him, so I would send them to Prabhakaran. He would choose the good ones and

would send back advice and comments.

My first photography field experience was on

Thavalai Pachchal (Operation

Frog Jumping) in 1993 in Poonakary. I already had much battle experience and

knew my place on the battleground, so I was comfortable being there. However,

being a photographer on the battleground is very different. I only had my

camera, I had no rifle. It felt very strange at first to be there with no gun. I

was excited and ready to take good photographs, but it rained all day and I

couldn’t get any pictures.

Since then, I have taken photographs of many battles and it is a very dangerous

job. The real danger is where I have to stand to take pictures. When you are a

fighter, you get to stay in camouflage, undercover and in the bunkers. When you

are a photographer, you have to be outside getting the pictures of the fighters.

I don’t think about death when I’m on the battlefield, I just try and get the

best pictures of my cadres — that is my mission and I don’t feel any fear.

I remember one time the LTTE started attacking Jaffna, they were moving forward

and the Sri Lankan Army was in retreat. I reached a beach I thought had already

been captured by the LTTE. I was walking without any fear; it was difficult to

walk because I was tired from the battle, but it helped me gather my thoughts

after the past days and hours of war. I saw some coconut trees, they were very

beautiful, they were bending as they grew. I wanted to take a picture of them,

after so many photographs of the fighting. I began to move closer to them.

Suddenly, I noticed a bunker under the trees and, at almost that moment, bullets

came towards me. I froze, realising it was a military bunker. I dived behind a

nearby tree and took cover, my heart pounding. There were only 10 metres between

the military and me. I had no choice but to run, and I did so as fast as I

could. A rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) passed over me and exploded in front of

me. As I ran, I laughed to myself — they had used an RPG shell for one girl!

About 50 metres from the military bunker, I reached the cadre bunker. I was

breathing heavily and then I heard the sound of a different gun, a sniper. I

looked at a female cadre who was beside me. She smiled at me. I understood at

that moment that someone in the bunker had taken the bullet. I checked myself to

see if I was injured. I was not bleeding, I was okay. The girl beside me was

slumped against the side of the bunker, still smiling at me. The other fighters

were frozen still. I shook her. There was no reaction from her; I couldn’t bear

it. Those rounds had been aimed at me but they had hit her. I cannot describe

what I felt at that moment.

I can never get over the feeling when a cadre is killed. We share meals,

laughter and adventure together, and then they are gone. I never get over that

loss. I too can die in the next second when I think of the people who died, and

when I see them die, I grow strong and fierce — like a Tiger. I touched her

gently, she rolled onto her back. There was no bleeding. I released the holster

around her chest and suddenly the blood shot out. Everyone understood what had

happened. Immediately they began first aid. We stopped the bleeding, and sent

her with the other cadres towards the medic. The military kept shooting at them

as they ran. I took up the girl’s rifle and started to fire to give them cover.

Other cadres also began to shoot and then the military stopped firing. My camera

was hanging around my neck, I didn’t even think to take it up. In this situation

I failed to take good pictures. It is very difficult to be in battle as a

fighting photographer and a journalist.

I’ve met many difficulties when I try to take pictures of fighters when they are

under cover, under trees and in the bunkers. I have to use my brain well. I have

to observe the enemy, where they are, what they are doing, what weapons they are

using, what formation they have formed. When the time comes, within a split

second, I have to take good pictures and get back to safety. My eyes and ears

are completely focused on the objective.

There is a high respect for photography in the LTTE and among the Tamil people.

I show my pictures to my whole team and to Prabhakaran and the other commanders.

They all encourage me, and say that I should do more. Some of my photographs

have appeared in newspapers in Sri Lanka, but they don’t always take the full

picture, they edit and cut the image. I remember how I once sent pictures of the

Point Pedro killings, there was so much bombing and shelling at that time. They

put the photographs in the newspaper, but censored them; they only showed the

faces of people, not the wounds or the amputations — it upset me because it did

not represent the truth.

My dream is Tamil Eelam. I have heard my people,

men and women, crying and screaming, I have

seen them dying, I have experienced

the tragedy of my people and my society. I have experienced far too much

violence and so many people suffering — from all this, my dream is to see these

people smile, living in a free homeland,

living a happy and good life.

Within the LTTE, I have gained many experiences, I have studied about the world,

about other struggles and wars, I have got to know many things. One thing that

we learn in the LTTE is that when you are given a job, you should do it one

hundred percent perfectly. There is little room for mistakes in the LTTE.

I am very proud that people are taking my photographs seriously now and that

they are going to other countries. I am very pleased that people are taking an

interest in my war-torn homeland. I am very thankful and happy that this is

happening, and I hope that people will understand them without discrimination.

|