|

Velupillai Pirabaharan - Rebel in the Family

Vinothini Rajendran sister of LTTE leader speaks

to Stewart Bell

Canadian National Post, 16 December 2008

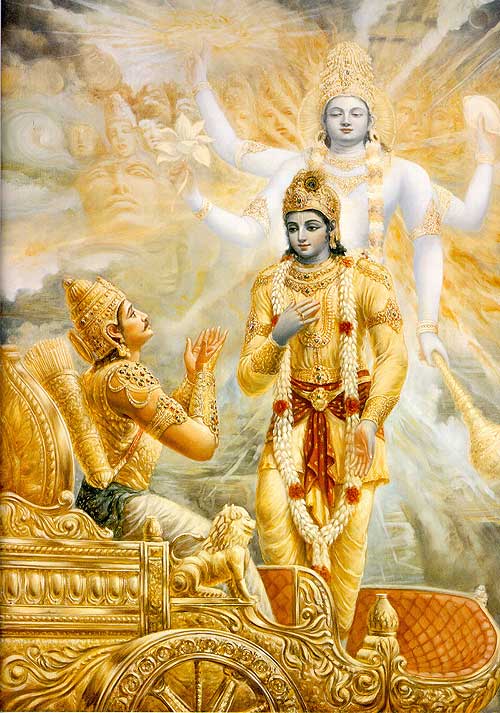

"... Ms. Rajendran says her brother is in no

danger. 'They won't be able to catch him' she says... A poster

of the Hindu hero Arjuna hangs on the wall. The Tamil script

below tells a story from the Bhagavad Gita about a conversation

between Lord Krishna and Arjuna, who is reluctant to go to war.

'Arjuna says, how can I fight my relatives?' ... Then Krishna

says, it is your duty. 'I am the God and I am telling you, you

do it'. Then he (Arujna) decides to fight. It was one of

Prabhakaran's favourite childhood stories... 'Once he accepts

something, he always finishes it... Father was like that' says

Ms.Rajendran. "

Excerpts of Interview...

Vinothini Rajendran says she has had no contact with her younger

brother, rebel leader Velupillai Prabhakaran, since moving to

Toronto in 1997. Vinothini Rajendran's 11th-floor apartment is

decorated with plastic flowers, a poster of Lord Krishna and framed

photos of the little brother she left behind in Sri Lanka.

It has been years since she saw him. He never writes or calls, but

she accepts that is just the way it is when your brother is

Velupillai Prabhakaran....

"It must be God's wish that he should become such a man," says Ms.

Rajendran, who immigrated to Canada more than a decade ago and lives

with her husband, Bala, in a modest apartment in east Toronto.

Despite being the sister of the Supreme Commander of the Liberation

Tigers of Tamil Eelam, Mrs. Rajendran has lived incognito in Toronto

since 1997, but she agreed to tell her story to the National Post.

For 25 years, her brother has led the LTTE, or Tamil Tigers, in a

civil war in Sri Lanka. His objective: independence for the ethnic

Tamil minority.

A folk hero to Tamil nationalists, Prabhakaran is wanted by Interpol

and has been condemned internationally for his tactics, which have

included hundreds of suicide bombings and the assassination of

senior politicians, including India's Rajiv Gandhi....

Sri Lanka has vowed to kill Prabhakaran and wipe out the Tamil

Tigers over the next few months. Last week, the military said it was

within "kissing distance" of the rebel stronghold, Killinochchi, but

Ms. Rajendran says her brother is in no danger. "They won't be able

to catch him," she says....

Ms. Rajendran describes her father as "very kind and soft

talking." He was highly disciplined. He never took bribes and

abstained from all vices, alcohol and cigarettes included. He worked

as a district land officer and volunteered as a trustee at the local

temple. "He was a religious-minded man, a Hindu," she says. The

family lived in Valvettithurai, a coastal village on Sri Lanka's

northern Jaffna peninsula, in a small house with a veranda and a

banana tree, enclosed within a fenced compound.

Vinothini was the third-born child. She was two years old when

Prabhakaran was born at Jaffna Hospital on Nov. 26, 1954. "As a

child, I was the pet and the darling of the family," Prabhakaran

told the

magazine Velicham in 1994. "My childhood was spent in the small

circle of a lonely, quiet house."

Vinothini would play with her baby brother, and fight with him. "He

was as normal as any boy," she says. "Normal, only he was reading a

lot." The house was full of books. Their mother was "a voracious

reader," Ms. Rajendran says. They would borrow books from friends or

the library.

Like his mother, Prabhakaran devoured history books, particularly

stories about the

Indian fighters who fought the British for independence. "It was

the reading of such books that laid the foundation for my life as a

revolutionary," he once said.

The Tamil-dominated northern region of Sri Lanka is a dry zone; much

of the soil is ill suited to farming. "So the people depended on

education and government jobs," Mr. Rajendran explained.

But following independence from Britain in 1948, the island's

ethnic

Sinhalese majority tried to limit Tamil access to universities and

civil service jobs. Tamil youths grew disillusioned with the

government and

turned to militancy.

Around the same time Prabhakaran took up arms, his father spoke to a

friend and they agreed that Vinothini and Bala would marry. The

family erected a temporary building in their compound to accommodate

wedding guests and shelter them from the sun and rain. The ladies

prepared vegetarian dishes in the kitchen. No invitations were

required; everyone knew they were welcome.

Prabhakaran was the best man. As is customary, he came by the

groom's house the day before the wedding to pay his respects. "He

was a very quiet man," Mr. Rajendran says. "He was smiling and his

eyes were piercing. He was lean."

A few months later, Prabhakaran formed the Tamil New Tigers, or TNT,

to wage an armed struggle against the Sri Lankan state security

forces. The group would later evolve into the Tamil Tigers.

"At that time, we knew he was doing something, but we didn't know it

was so serious," Mr. Rajendran says. They thought he was only

putting up political posters. They only learned of his paramilitary

activities when police came calling at the family home in 1972.

Prabhakaran slipped out the back and disappeared.

"After that he stopped coming to the house," Ms. Rajendran says.

Prabhakaran told the Indian journalist Anita Pratap that, "As

soon as the Tiger movement was formed, I went underground and lost

contact with my family ... They are reconciled to my existence as a

guerrilla fighter."

The Rajendrans were living in the capital, Colombo, when Prabhakaran

ignited the civil war with an ambush attack against Sri Lankan

soldiers. Mr. Rajendran promptly lost his job at an import-export

firm; his employer found out about the family connection and didn't

want any trouble. "I was asked to leave," he says.

They spent a week at a refugee camp and

then sailed back to Jaffna. Six months later, Mr. Rajendran went

to Jeddah to work as a deckhand on a ship on the Red Sea. Mrs.

Rajendran stayed in Jaffna, but the police gave her a hard time

about her notorious brother so the family decided to leave for

India.

Thousands of Sri Lankan Tamils had sought refuge around Madras.

The Rajendrans registered with the police and rented a house. Mr.

Rajendran taught English and ran a consultancy service that helped

Tamils submit applications to immigrate to Canada and Australia.

Prabhakaran was also exiled in India at the time, running his

guerrilla war from a Madras safe house. The Rajendrans saw him there

at a family function, a cousin's wedding. "He came in a jeep with

four or five boys," Mr. Rajendran says. They saw him again just

before he returned to Sri Lanka. "He talked to us and said he is

going."

Tired of refugee life in southern India, the Rajendrans travelled to

Canada, arriving on Oct. 27, 1997. They have returned to Sri Lanka

only once, in 2003, to help Ms. Rajendran's parents move back to Sri

Lanka from India. It was the first time she had seen her homeland in

almost two decades. The north was a desolate landscape of ruined

buildings, destroyed by incessant shelling. The lush gardens of her

youth had gone to weeds.

A red-and-yellow Tamil Tigers flag hangs in her living room in

Toronto, but Ms. Rajendran says she is not politically active.

Neither she nor her husband attends Tamil community events in

Toronto, with the exception of

Heroes Day, the annual commemoration of fallen rebels.

Ms.

Rajendran does not work; her English is awkward. Her husband works

part-time at a furniture store. His hands shake like he is nervous,

but he explains he has Parkinson's Disease. Ms.

Rajendran does not work; her English is awkward. Her husband works

part-time at a furniture store. His hands shake like he is nervous,

but he explains he has Parkinson's Disease.

A poster of the Hindu hero Arjuna hangs on the wall. The Tamil

script below tells a story from the

Bhagavad Gita about a conversation between Lord Krishna and

Arjuna, who is reluctant to go to war. "Arjuna says, how can I fight

my relatives?" Mr. Rajendran explains. "Then Krishna says, it is

your duty. I am the God and I am telling you, you do it. Then he

decides to fight." It was one of Prabhakaran's favourite childhood

stories.

Every so often, Ms. Rajendran gets a letter from her parents in

Killinochchi, but she has had no contact with her younger brother

since coming to Canada. She only hears stories about him.

She believes he will not give up his fight for Tamil independence.

Because he started it, he feels obliged to see it through, she says.

"Once he accepts something, he always finishes it," she says.

"Father was like that."

|