It is said that in the area of religion that which

is the truth defies description and that which is

described is never the truth: or as the saying goes in

Tamil - Kandavan Vindilan, Vindavan Kandilan.

There is a story that is related of Bodhirama that

he had once gathered his disciples about him to test

their perception. One of the pupils said, 'In my

opinion truth is beyond affirmation or negation.'.

Bodhirama replied 'You have my skin'. Another disciple

said, 'In my view it is like Ananda's sight of the

Buddha - seen once and forever', and Bodhirama said,

'You have my flesh'. And, then as the story goes, the

third disciple came before Bodhirama and was silent,

and Bodhirama said, 'You have my marrow.'

Discussion and dialogue in the area of religion are

but parts of skin and flesh - not the marrow - a marrow

which is never found in words.

The inquisitive and inquiring mind of man has

through the centuries sought to understand that which

is beyond words. The mind itself represents a stage and

by no means the final stage, in an evolutionary process

which has witnessed a continuing change from inanimate

to animate, from stone to plant to animal to man, and

each stage has

brought with it a greater degree of

consciousness.

It is an

evolutionary process which has resulted in the

formation of the seemingly intricate fore brain of man

today and it is this self conscious mind of man which

seeks to know, which seeks to understand.

How is this understanding brought about? In what way

does an ordinary mind comprehend?

One says ordinary mind because one can neither

reject nor ignore the experience of those extraordinary

beings who have arisen on this earth from time to time

and who appear to have comprehended the total reality

and who were one with it; enlightened beings to whom

time and space dissolved in an eternity which was

boundless.

In some way they appear to have transcended the

limitations of the self conscious mind and their lives

have afforded a living testimony, for those who wish to

see, of what is perhaps an innate capacity in each one

of us to perceive the whole and become holy. Because,

it seems to me that is what holiness is about - the

capacity to perceive the whole, the capacity to

understand the total reality in its entirety, unbounded

by space and unbounded by time.

The ordinary mind does not however comprehend the

whole. It seems to deal effectively only with parts of

the total reality. It directs its attention to discrete

and separate parts of the whole. In order that it may

understand, the mind separates and conceptualises. It

separates that which is connected and the very process

of separation distorts an understanding of the

whole.

The mind thinks in sequence in time. The present is

a fleeting moment and is then gone forever. Thoughts

are so much grist to its mill. Words and concepts are

the instruments of its trade. The mind seeks to clarify

one concept by having recourse to another. It defines

one word with another. There is no end to this process

nor is there a starting point.

The mind

deals in opposites. There is no idealism without

materialism; there are no means without ends; there is

no detachment without attachment; there is no free will

without determinism; there is no good without bad. If

everything was good what would it mean? Presumably, we

would stop using the word. The mind speaks of theses,

antithesis and synthesis and describes this as the

dialectical process. And every synthesis is another

thesis and gives rise to another antithesis and yet

another synthesis - and the process is endless. The

mind then speaks of dialectical idealism and

dialectical materialism.

The need to use opposites is the need of the mind

that lives in the duality of I and not I, and the mind

extends this duality, extends these seeming opposites,

to everything that it deals with. And more often than

not, it

does not stop to ask: who am 'I'? Are there two

'I's - the one who asks the question and the other,

about whom the question is asked?

The inquiring and inquisitive mind - the restless

mind, the monkey mind of man - allows one thought to

play with another and ends up with what it then

triumphantly describes as a rationalisation. The mind

discovers seemingly broader and broader concepts and

seemingly more and more general laws. But what is the

result?

From the vantage point of each new law, the mind

then perceives an increasing area of the unknown and

greater and greater areas of the unknown come within

the vision of man. The search for fundamental laws, the

search for fundamental particles, the search for

absolute truths, inside the trap of duality is in the

nature of an adventure to possess an ever receding

mirage.

"...reason cannot arrive at any final truth

because it can neither get to the root of things nor

embrace their totality. It deals with the finite, the

separate and has no measure for the all and the

infinite." - The Future Evolution of Man - Sri

Aurobindo

But that is not to say that the mind does not have

an important role to fulfil.

" .... reason has a legitimate function to fulfil,

for which it is perfectly adapted; and this is to

justify and illumine for man his various experiences

and to give him faith and conviction in holding on to

the enlarging of his consciousness." -

The Future Evolution of

Man - Sri Aurobindo

In India, which to many of us is the cradle of

civilisation, there were humans who thousands of years

ago used the mind but who were not entrapped in it; who

did not turn away from the mind but who pushed the

frontiers of the mind and transcended it in their quest

to understand - a quest which ended in the realisation

that there was no quest after all. Swami

Chinmayananda is a living descendent of that great

Indian tradition. That which he has said and written

has enabled many to find a new understanding of

themselves - and nobody understands anything if he has

not understood himself.

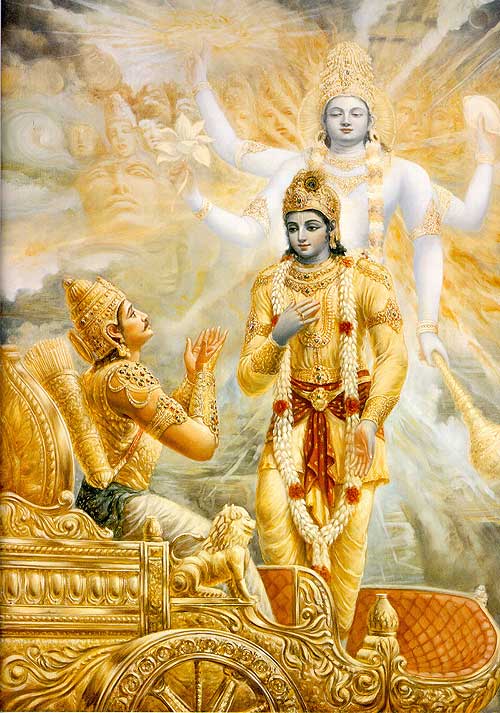

Those who have heard Swami Chinmayananda on the

Bhavad Gita

have come away with a fresh awareness and some insights

- insights which in the end they themselves will need

to integrate in their being. That which they hear must

relate to that which is within their experience.

Otherwise words only make noise.

That which was said by Lord Krishna to Arujna in the

battlefield was both simple and fundamental - simple to

declare but fundamental in content. It was a call for

action in the battlefield and where else is there a

greater need for action. And Lord Krishna urging Arjuna

to do battle against those whom Arjuna regarded as his

friends, his teachers and his relations, tells Arujna,

"To action you have a

right, but not to the fruits thereof."

This oft repeated statement of the Gita is of very

direct relevance to all of us who are engaged in

activity or action of one kind or another. The

detachment which the Gita speaks about is not the

opposite of attachment. It is not a dead detachment. It

is not a negative detachment. Understanding the Gita is

not a mere intellectual exercise in the trap of

opposites.

There is in each one of us an urge to live without

conflict, without opposites, to understand the

whole and become holy. There is in each one of us a

path of harmony, our dharma, and it is this path of

harmony which the Gita enjoins us to follow. For Arujna that

path was to engage in battle.

Swami

Chinmayananda, who is perceived by many as

one of the great living exponents of the teachings of

the Gita, has made a significant contribution to

further our understanding of ourselves and there is

much that we can learn from that which he has said and

from that which he has written.