Kosovo

is set to declare its independence from Serbia this Sunday. In his four hour

long valedictory media conference, outgoing Russian President Vladimir Putin has

denounced the move as "illegal and immoral". Serbia and Russia have called for

an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council. Russia, China, India and South

Africa are among the countries which have opposed Kosovo's declaration of

independence. The open secession of Kosovo and its imminent recognition by

powerful Western states takes place notwithstanding UN Resolution 1244 of 1999

which recognises Kosovo as part of Serbia. As the Russian Federation's

charismatic Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (who stunned me by a burst of fluent

Sinhala upon introduction) warned in his Gunnar Myrdal Lecture in Geneva a few

days back, the recognition of Kosovo's independence runs contrary to the very

basis of international law and is fraught with consequences for Europe and other

parts of the world.

Kosovo

is set to declare its independence from Serbia this Sunday. In his four hour

long valedictory media conference, outgoing Russian President Vladimir Putin has

denounced the move as "illegal and immoral". Serbia and Russia have called for

an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council. Russia, China, India and South

Africa are among the countries which have opposed Kosovo's declaration of

independence. The open secession of Kosovo and its imminent recognition by

powerful Western states takes place notwithstanding UN Resolution 1244 of 1999

which recognises Kosovo as part of Serbia. As the Russian Federation's

charismatic Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov (who stunned me by a burst of fluent

Sinhala upon introduction) warned in his Gunnar Myrdal Lecture in Geneva a few

days back, the recognition of Kosovo's independence runs contrary to the very

basis of international law and is fraught with consequences for Europe and other

parts of the world.

�The Kosovo crisis sheds light on a dynamic in world politics

which is of central importance to Sri Lanka. This is the matter of state

sovereignty. As a country which is grappling with a challenge to its territorial

integrity and unity, all tendencies towards the break-up of established states

are against the basic interests of Sri Lanka.�

The Russian position has consistently been that any solution

should be agreed upon in negotiations between Serbia and Kosovo. This was

abandoned as impossible by Marti Ahtissari, who recommended de facto

independence for Kosovo. Incidentally he was brought to Sri Lanka as a possible

negotiator or facilitator by the Ethnic Affairs Advisor of President

Kumaratunga, but luckily for Sri Lanka was objected to by Lakshman Kadirgamar

and, it must be admitted, the JVP.

There were options other than secession for Kosovo. One was for

the fullest autonomy within Serbia. The other was the carving out of the Serbian

majority portion of Kosovo and its annexation with Serbia. However, all options

were aborted by the obduracy of the Kosovo leadership, which insists on

independence. It must be noted that the current leader of Kosovo is a former

leader of the separatist army which practised terrorism, the Kosovo Liberation

Army (KLA). The majority of people of Kosovo had become accustomed to the idea

of independence during the several years of administration by a UN High

Commissioner (later nominated as an IIGEP member for Sri Lanka by the EU).

The hardening of the position of Kosovo was also due to open

pledges of recognition of independence by several key Western powers.

Of course the breakaway of Kosovo merely completes the

unravelling of the former Yugoslavia. There were many reasons for this: the

abandonment by majority Serbian ultra-nationalists, in the new context of

electoral competition, of the enlightened compact forged by the unorthodox

Communist Joseph Broz Tito, a founder leader of the Non-Aligned Movement (and

friend of Sri Lanka); the exacerbation of ethnic tensions by the adoption of an

IMF package; the rollback by Serb nationalism of Kosovo's autonomous status as a

province; recognition by certain Western European states of the breakaway

Yugoslav republics setting off a centrifugal chain reaction; the excessive

brutality against civilians of the Serbian army and Serb militia in the

breakaway republics; the partiality of the Western media which focussed only on

Serb excesses but not those committed by anti-Serb forces.

In the final instance however, the secession of Kosovo is

traceable to a single mistake: the decision by President Milosevic to follow the

advice of President Yeltsin (who had already been lobbied by the US), and

withdraw the Yugoslav army from Kosovo, notwithstanding the fact that in its

heavily camouflaged and dug-in positions, it had withstood US/NATO bombing and

was well positioned to inflict, with its tradition and training in partisan

warfare, unacceptable casualties on any invading ground forces.

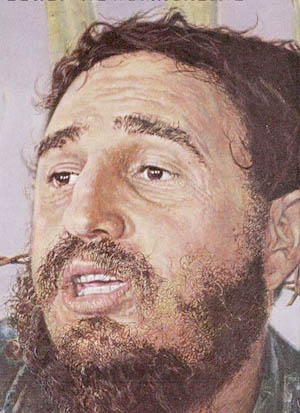

Cuban leader Fidel Castro reveals that at this

crucial moment he had written to Milosevic and urged him, in the

final words of his missive, to "Resist! Resist! Resist!", but

the Belgrade leadership failed to do so. In short, the impending

independence of Kosovo is the result of the failure of political

will on the part of the ex-Yugoslav leadership. Instead of

resisting, the Yugoslav army withdrew and was replaced by an

international presence on the ground in Kosovo. After a period

of tutelage, Kosovo was encouraged with a nod and a wink, to

secede completely.

These then are the lessons for Sri Lanka: never withdraw the

armed forces from any part of our territory in which they are

challenged, and never permit a foreign presence on our soil.

After 450 years of colonial presence, and especially after the

experience of the Kandyan Convention, we Sri Lankan should have

these lessons engraved in our historical memory and our

collective identity. The Western imperialists who failed to

capture our island militarily were able to take control of it

only because we double crossed our leader, trusted the West,

signed an agreement and allowed the foreign presence into our

heartland.

The Western war against Yugoslavia was waged not by the Bush

administration but by a liberal one. It was waged under the

doctrine of liberal internationalism, and humanitarian

interventionism. These doctrines were updated to "preventive

humanitarian interventionism" in the case of the invasion of

Iraq. Today, the buzzword is the "Responsibility to Protect",

and I refer not to the UN World Leaders summit of 2005 which

requires the endorsement of the Security Council, but the

original 1998 version of the Canadian government sponsored

International Commission on State Sovereignty, which had a far

more elastic interpretation! The co-chairman of that Commission

was former Australian Foreign Minister Gareth Evans (whom

Lakshman Kadirgamar was determined, should not play a role in

Lanka's peace process despite his offers to do so in 1995).

We may find a newer version arising with UK Foreign Secretary

David Miliband's Aung San Suu Kyi lecture delivered at Oxford

University a few days back. In it, he says that notwithstanding

some mistakes in Iraq and Afghanistan, the West must not forget,

and must take up once again, its moral imperative to expand

democracy throughout the world (including, interestingly enough

in "established democracies").

He identifies and rejects three objections to

that project: the "Asian values" school which in its 1993

variant of a statement by 34 countries, recognises democracy but

resist the imposition of western values as neo-colonial; the

Realpolitik school which stresses "interests" rather than values

and morality; and even the pragmatic school which points out

that democracy is the product of internal historical processes.

Foreign Secretary Miliband makes several pointedly critical

references to China, (which he will be visiting shortly) in his

speech on the need of the West to extend democracy worldwide.

The patterns of world politics appear kaleidoscopic, with

coalitions forming over one issue, only to break up over

another. At first glance this would make long term alliances or

affiliations almost impossible. However, certain issues are

revelatory of underlying dynamics which are of a defining

character. Kosovo is certainly one such issue.

The Kosovo crisis sheds light on a dynamic in world politics

which is of central importance to Sri Lanka. This is the matter

of state sovereignty. As a country which is grappling with a

challenge to its territorial integrity and unity, all tendencies

towards the break-up of established states are against the basic

interests of Sri Lanka.

The issue of Kosovo not only illustrates the phenomenon of

secessionism. It reveals a more fundamental contradiction within

world politics, namely that between state sovereignty on the one

hand and those tendencies which act to undermine states. Such

tendencies are twofold: secessionism from within and hegemonism

from without. The tendency towards hegemonism manifests itself

most starkly in the phenomenon of interventionism.

Kosovo and earlier Chechnya disprove the identification that

some make between Western interventionism and particular

religions. While it is true that on a global scale, the West

perceives itself as besieged by and struggling against what it

calls Islamist terrorism or Islamic radicalism/extremism (some

hard-line ideologues even talk of Islamo-fascism) attention must

be drawn to the fact that Serbs are Christian, while Kosovo

Albanians are Islamic. The Chechen separatists, some of whom

were headquartered in the West, were also Islamic, while Russia

is mainly Christian. Western interventionism is not tied to any

particular ethnic or religious group. The name of the game seems

the old one of divide and rule, and whichever group or struggle

weakens the target state appears to be the one that is afforded

patronage.

All tendencies in world politics which weaken, fragment and

destabilise states, undermining their sovereignty and making

them vulnerable to hegemony and intervention, are inimical to

Sri Lanka. All tendencies which strengthen and defend state

sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity, are friendly and

helpful towards Sri Lanka. By extension, all state and non-state

actors which work towards the weakening of state sovereignty in

the non metropolitan areas of the world, i.e. the global South

and East, cannot be regarded as the strategic friends, allies

and partners of Sri Lanka. All state and non�state actors which

support, defend and work towards the preservation and

strengthening of the sovereignty, independence, unity and

territorial integrity of states, are objectively the friends,

allies and partners of Sri Lanka.

"No real change in history has ever been achieved by discussions

alone... Freedom is not given, it is taken.. One individual may die

for an idea; but that idea will, after his death, incarnate itself in a

thousand lives. That is how the wheel of evolution moves on...The

freedom that we shall win through our sacrifice and exertions, we

shall be able to preserve with our own strength..

"No real change in history has ever been achieved by discussions

alone... Freedom is not given, it is taken.. One individual may die

for an idea; but that idea will, after his death, incarnate itself in a

thousand lives. That is how the wheel of evolution moves on...The

freedom that we shall win through our sacrifice and exertions, we

shall be able to preserve with our own strength..