|

Conflict

Resolution: Tamil Eelam - Sri Lanka

The Limits of State Sovereignty:

The Responsibility to Protect in the 21st Century

Gareth Evans,

President, International Crisis Group

& Former Australian Foreign Minister

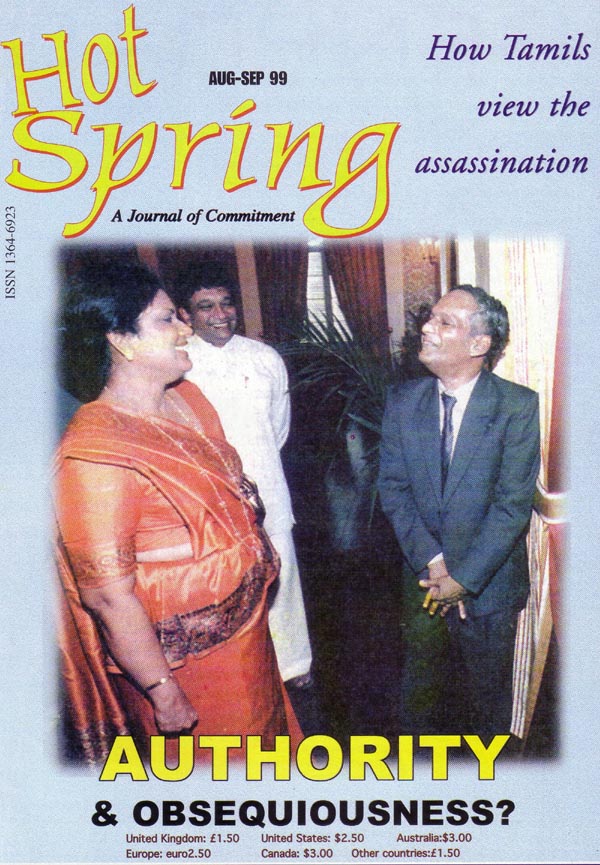

Eighth Neelan Tiruchelvam Memorial Lecture

at International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES),

Colombo, 29 July 2007

Comment

(1) by tamilnation.org

The

one question that Mr.Gareth Evans signally failed

to address was the content of the strategic

interests of the so called 'international community' (including

Australia) in the island of Sri Lanka and in the

Indian Ocean region - a question made all the more

relevant by his passing reference to

"various

foreign states" who "bear some of the responsibility

for allowing the Tigers to build up their power over the

years".

One of the

matters that both

Washington

and

New Delhi

(and for that matter,

China) may want to address is whether the approaches

that each of them have adopted in relation to the

conflict in the island of Sri Lanka will lead to a

resolution of the conflict between their own

strategic interests (in the context of the

two geopolitical triangles juxtaposing on the Indian

Ocean's background: U.S.-India-China relations and

China-Pakistan-India relations) - and whether there is a

need for each of them to re-evaluate these strategic

interests, if the conflict in the island is to be

resolved. After all, it will be fair to say that there

are two conflicts in the island - one the conflict

between the Sinhala nation and a

Tamil Eelam nation seeking freedom from alien Sinhala

rule, and the other the conflict between the

international actors in the

Indian Ocean region seeking, (amongst other matters)

control of the Indian Ocean sea lanes - whether

through a string of pearls or

by other means. All of us (including Mr.Evans)

may gain by paying more attention to the words

Marcus Aurelius, some 1800 years ago in A.D.169

: 'Look back over the past, with its changing

empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the

future, too.' Struggles for freedom and justice are not

easily demonised and/or suppressed..." [see also

Comment

(2) and Comment

(3)

and

Comment (4)

by tamilnation.org] Comment

(1) by tamilnation.org

The

one question that Mr.Gareth Evans signally failed

to address was the content of the strategic

interests of the so called 'international community' (including

Australia) in the island of Sri Lanka and in the

Indian Ocean region - a question made all the more

relevant by his passing reference to

"various

foreign states" who "bear some of the responsibility

for allowing the Tigers to build up their power over the

years".

One of the

matters that both

Washington

and

New Delhi

(and for that matter,

China) may want to address is whether the approaches

that each of them have adopted in relation to the

conflict in the island of Sri Lanka will lead to a

resolution of the conflict between their own

strategic interests (in the context of the

two geopolitical triangles juxtaposing on the Indian

Ocean's background: U.S.-India-China relations and

China-Pakistan-India relations) - and whether there is a

need for each of them to re-evaluate these strategic

interests, if the conflict in the island is to be

resolved. After all, it will be fair to say that there

are two conflicts in the island - one the conflict

between the Sinhala nation and a

Tamil Eelam nation seeking freedom from alien Sinhala

rule, and the other the conflict between the

international actors in the

Indian Ocean region seeking, (amongst other matters)

control of the Indian Ocean sea lanes - whether

through a string of pearls or

by other means. All of us (including Mr.Evans)

may gain by paying more attention to the words

Marcus Aurelius, some 1800 years ago in A.D.169

: 'Look back over the past, with its changing

empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the

future, too.' Struggles for freedom and justice are not

easily demonised and/or suppressed..." [see also

Comment

(2) and Comment

(3)

and

Comment (4)

by tamilnation.org]

[see also

Australia's Expansive Asian Security Footprint

"The (Australian 2007) Defence Update is a deeply flawed policy

document... Double standards on core issues abound...In East

Asia, Australia supports "Japan's more active security posture

within the US alliance and multinational coalitions". But

Chinese military modernization "could create misunderstandings

and instability in the region .... (Then there) ...is the

elephant in the room problem: the obvious and undoubted

perceived interest -- a perceived benefit to Australia from

western access to oil -- cannot be mentioned in polite

company... even when the dirty secret is admitted, even if only

in only in conclaves of trusted experts, it is soon clear that

it is not at all certain that the security of the Australian

people can be shown to be affected by who owns the oil fields of

Iraq.."

more]

Today

more than ever, on this eighth anniversary of his assassination, Sri

Lankans and those in the wider international community need to

remember and be re-inspired by Neelan Tiruchelvam's life and

achievements. While we can no longer benefit directly from his

remarkable intelligence and learning, his boundless energy, his

politic commitment, and his optimism, we do still have his spirit

living among us in the ideas and institutions he gave us, and in the

example he set for us of an engaged intellectual and a principled

politician. Today

more than ever, on this eighth anniversary of his assassination, Sri

Lankans and those in the wider international community need to

remember and be re-inspired by Neelan Tiruchelvam's life and

achievements. While we can no longer benefit directly from his

remarkable intelligence and learning, his boundless energy, his

politic commitment, and his optimism, we do still have his spirit

living among us in the ideas and institutions he gave us, and in the

example he set for us of an engaged intellectual and a principled

politician.

Neelan was an extraordinary institution builder. The best known of

those he helped found are our host institution tonight, the

International Centre for Ethnic Studies (ICES), so ably and

imaginatively now led by Dr Rama Mani, and the Law and Society Trust

(LST) � both of which continue to make their intellectual and

political mark not only in Sri Lanka and South Asia, but across the

globe. Beyond that Neelan played an important role in creating the

Official Languages Commission, the Human Rights Task Force and later

the Human Rights Commission, as well of course as his own

distinguished law firm, Tiruchelvam Associates, now led by his wife

Sithie. His ability to build and maintain institutions was the

product not only of good ideas and hard work but also of his ability

to inspire others � particularly young people � to see, believe in,

and work for otherwise hidden possibilities.

Of course the institutions he believed above all worth building were

effective, decent states � protecting the rights and interests of

all their peoples, with conflicts and disputes being resolved

through law, democratic process and effective government structures,

not violence. Probably best known internationally as a brilliant

constitutional lawyer, Neelan was closely involved in

constitution-making processes in Kazakhstan, Ethiopia, and Nepal,

but above all he will be remembered as a central architect of the

then Sri Lankan government's groundbreaking constitutional proposals

of the mid- and late-1990s, which while unhappily never ratified,

continue to inspire hope that a consensus on a just constitutional

and political settlement is, in fact, within reach should only the

political will be there.

Neelan knew that political will is never waiting in a cupboard to be

found: it has to be nurtured and generated, campaigned for

persistently and relentlessly. He was an impressive scholar � with

academic interests and writings spanning a remarkable range of

topics from South Asian culture and ethnicity, to gender, political

theory and of course constitutional law. But he refused to limit

himself to mere scholarship, believing the obvious risks and

challenges of politics were necessary for the ideas he believed in

to be brought to life, to be made real in people's lives. And it was

his willingness to engage in electoral politics as a member of the

TULF and his work in parliament and through other government

mechanisms that ultimately, tragically for him, his family and all

of us, cost him his life.

There is one other celebrated aspect of Neelan Tiruchelvam's life

and character that is directly relevant to my main topic tonight,

and that is his cosmopolitanism. Neelan's sense of community and

attachment went beyond ethnicity, beyond religion, beyond nation,

and beyond region. He didn't ignore or reject any of those

particular attachments in the name of an empty universality, but

rather attempted to connect them all in a more vibrant, integrated,

and just whole. He argued that developing states not only had

something to learn from the richer, developed states but also

something to teach them, arguing for instance, that the

individualist discourse of human rights born in the West "needs to

be enriched by explicit reference to the religious and cultural

traditions of South Asia." And he argued strongly, too, that it was

only if Western states themselves actively tried to live up to their

own professed principles, and applied them in evenhanded ways, that

their concern with human rights in non-Western countries could begin

to be taken seriously.

Approaching issues in this integrated way, confident of the

contributions his own country and culture and region could make to

wider international discourse, led Neelan to have no fear of

international involvement designed to assist countries like his own

extricate themselves from particular crises, or cycles of violence

and counter-violence in which they seemed to be trapped. What

mattered was whether that involvement was not only effective, but

principled and consistent.

This leads directly into my subject tonight: the limits of state

sovereignty, and the proper role of the international community in

responding to catastrophic human rights violations � genocide and

other mass killing, large-scale ethnic cleansing and crimes against

humanity � occurring within the boundaries of a single country.

There is a widespread concern that involvement of countries in the

affairs of others, and in particular the involvement of developed

countries in the internal affairs of developing ones, has not always

been principled or consistent in the past. It is an article of faith

around a good deal of the global South that Article 2 (7) of the UN

Charter is to be read as an all-embracing prohibition when it says

that "Nothing should authorise intervention in matters essentially

within the domestic jurisdiction of any State".

It is understandable that sovereignty should be a very sensitive

subject indeed with the many states who gained their independence

during the decolonisation era � states in all cases proud of their

new identity, in many cases conscious of their fragility, and

generally inclined to see the non-intervention norm as one of their

few defences against threats and pressures from more powerful

international actors seeking to promote their own economic and

political interests.

But the trouble with this approach, like anything taken to extremes,

is that it has had a terrible downside, one which came to a head in

the 1990s in the international response to the series of

conscience-shocking man-made catastrophes that erupted in the

Balkans and Central Africa � most horribly the genocide in Rwanda in

1994, followed by the almost unbelievable default in Srebrenica just

a year later. Over and again, when situations seemed to cry out for

some response, the international community reacted erratically,

incompletely, counterproductively or not at all. And when killing

and ethnic cleansing started all over again in Kosovo in 1999, and

the international community did in fact intervene militarily as it

probably should have, it did so without the authority of the

Security Council in the face of a threatened veto by Russia, raising

anxious questions about the integrity of the whole international

security system.

The great debate throughout the 1990s was about the competing claims

of intervention and state sovereignty. One side of the argument was

the concept, coined by Bernard Kouchner, the founder of Medicines

Sans Frontier and now France's Foreign Minister, of 'droit

d'ing�rence' � the 'right to intervene', or, more fully, the 'right

of humanitarian intervention'. But while, from many perspectives

this was a noble and effective rallying cry � with a particular

resonance in the global North � around the rest of the world it

enraged as many as it inspired. On the other side, equally

vehemently claims, mostly coming from the global South, were made

about the primacy and continued resonance of the concept of national

sovereignty. Battle lines were drawn, trenches were dug, and verbal

missiles flew: the debate was intense and very bitter, and the 1990s

finished with it utterly unresolved in the UN or anywhere else.

UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan at one stage made his own effort to

resolve the conceptual impasse at the heart of this debate by

arguing that national sovereignty had to be weighed and balanced in

these cases against individual sovereignty, as recognised in the

international human rights instruments. But this fell on deaf ears,

being seen not so much as resolving the dilemma of intervention but

restating it. In his report to the General Assembly in 2000, the

Secretary-General brought the issue to a very public head, saying in

language that was both moving and agitated, and which resonates to

this day: If humanitarian intervention is indeed an unacceptable

assault on sovereignty, how should we respond to a Rwanda, to a

Sebrenica, to gross and systematic violations of human rights?

The task of meeting this challenge fell, in the event, to

International Commission on Intervention and State Sovereignty

(ICISS), sponsored by the Canadian Government, which I had the

privilege of co-chairing, along with the Algerian diplomat and

veteran UN Africa adviser Mohamed Sahnoun. We presented our report,

entitled The Responsibility to Protect, at the end of 2001. The

Commission made what are generally now acknowledged to be two

critical conceptual contributions to resolving this increasingly

ugly and sterile debate.

The first was to invent a new way of talking about 'humanitarian

intervention'. We sought to turn the whole weary � and increasingly

ugly � debate about the 'right to intervene' on its head, and to

recharacterise it not as an argument about the 'right' of states to

anything, but rather about their 'responsibility' � one to protect

people at grave risk: the relevant perspective, we argued, was not

that of prospective interveners but those needing support. The

searchlight was swung back where it should always be: on the need to

protect communities from mass killing and ethnic cleansing, women

from systematic rape and children from starvation. We very much had

in mind the power of new ideas, or old ideas newly expressed, to

actually change the behavior of key policy actors. And a model we

very much had in mind in this respect was the Brundtland Commission,

which a few years earlier had introduced the concept of 'sustainable

development' to bridge the huge gap which then existed between

developers and environmentalists. With a new script, the actors have

to change their lines, and think afresh about what the real issues

in the play actually are.

The second big conceptual contribution of the Commission, linked

with the first, was to insist upon a new way of talking about

sovereignty itself: we argued, building on an earlier formulation by

Francis Deng (the Sudanese scholar and diplomat now named by UN

Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon as his Special Adviser for the

Prevention of Genocide and Mass Atrocities) that its essence should

now be seen not as 'control', as in the centuries-old Westphalian

tradition, but, again, as 'responsibility'. The starting point is

that any state has the primary responsibility to protect the

individuals within it. But that is not the finishing point: where

the state fails in that responsibility, through either incapacity or

ill-will, a secondary responsibility to protect falls on the wider

international community. That, in a nutshell, is the core of the

responsibility to protect idea, or 'R2P' as we are all now calling

it for short.

After laying these foundations, the Commission spelled out what the

responsibility to protect should mean in practice. Certainly it

means reacting effectively in situations where genocide, ethnic

cleansing, war crimes and crimes against humanity are currently

occurring or imminent. But it also means preventing situations, not

yet at that conscience-shocking stage but capable of reaching it,

from so deteriorating. And it means rebuilding societies shattered

by such catastrophes to ensure they do not recur.

The action required by R2P is overwhelmingly, preventive: building

state capacity, remedying grievances and ensuring the rule of law.

But if prevention fails, R2P requires whatever measures � economic,

political, diplomatic, legal, security, or in the last resort

military � become necessary to stop mass atrocity crimes occurring.

As to who should in practice bear the responsibility in question,

for individual states, R2P means in the first instance the

responsibility to protect their own citizens from such crimes, and

to help other states build their capacity to do so. For

international organizations, including the United Nations, R2P means

the responsibility to warn, to generate effective preventive

strategies, and when necessary to mobilize effective reaction. For

civil society groups, R2P means the responsibility to force the

attention of policy-makers on what needs to be done, by whom and

when.

It is one thing to develop a concept like the responsibility to

protect, but quite another to get any policy maker to take any

notice of it. The most interesting thing about the Responsibility to

Protect report is the way its central theme has continued to gain

traction internationally, even though it was almost suffocated at

birth by being published in December 2001, in the immediate

aftermath of 9/11, and by the massive international preoccupation

with terrorism, rather than internal human rights catastrophes,

which then began.

In just five short years, a remarkably brief time in the history of

ideas, the responsibility to protect concept evolved from a gleam in

an international commission�s eye, to what now has the pedigree to

be described as a broadly accepted international norm, and one with

the potential to evolve further into a rule of customary

international law.

The concept was first seriously embraced in the doctrine of the

newly emerging African Union, and over the next two to three years

it won quite a constituency among academic commentators and

international lawyers. But the big step forward came with the UN

60th Anniversary World Summit in September 2005, which followed a

major preparatory effort involving the report of the 2004 High Level

Panel on new security threats (of which I was, rather conveniently,

a member) which fed in turn into a major report by the

Secretary-General himself. Both these reports emphatically embraced

the responsibility to protect concept, and the Summit Outcome

Document, unanimously agreed by the more than 150 heads of state and

government present and meeting as the UN General Assembly,

unambiguously picked up their core recommendations.

A further important conceptual development has occurred since the

September 2005 Summit: the adoption by the Security Council in April

last year of a thematic resolution on the Protection of Civilians in

Armed Conflict which contains, in an operative paragraph, an express

reaffirmation of the World Summit conclusions relating to the

responsibility to protect. And we have now begun to see that

resolution in turn now being invoked in subsequent specific

situations, as with Resolution 1706 of 31 August 2006 on Darfur. A

General Assembly resolution may be helpful, as the World Summit�s

unquestionably was, in identifying relevant principles, but the

Security Council is the institution that matters when it comes to

executive action. And at least a toehold there has now been carved.

But, for those of us who believe in R2P, this is just about where

the good news ends. We are deluding ourselves if think the battle is

won, in the sense that when the next R2P situation comes along,

involving large-scale killing, or ethnic cleansing, or other crimes

against humanity, or all of the above, within a sovereign state's

borders � as surely some such situation will, some time, some where,

and maybe sooner than we think � there really will be a shared,

instinctive, reflex global response. A response not only of horror

that something which we have all said should happen 'never again' is

in fact happening again. But a response which makes something

happens � mobilizing effective international action to actually stop

the threat.

As someone who has been speaking and writing on this subject around

the world for several years now, I have been well aware that the

consensus reached at the World Summit was based on fairly fragile

foundations. In 2005, a fierce rearguard action was fought, almost

to the last, by a small group of developing countries, joined by

Russia, who basically refused to concede any kind of limitation on

the full and untrammeled exercise of state sovereignty, however

irresponsible that exercise might be. What carried the day in the

end was not so much consistent support from the EU and U.S. �

support which after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 was not

particularly helpful, it has to be acknowledged, when it came to

meeting these familiar sovereignty concerns. The support that

mattered, rather, was persistent advocacy by sub-Saharan African

countries, led by South Africa; a clear � and historically quite

significant � embrace of limited-sovereignty principles by the key

Latin American countries; and some very effective last minute

personal diplomacy with major wavering-country leaders, including

India in particular, by Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin.

In my travels since 2005, I have become fairly accustomed to hearing

suggestions from the representatives of a number of countries, not

least in Asia � and not excluding diplomats from Sri Lanka � that

while they had not been prepared to break consensus and oppose R2P

language outright in 2005, they had been less than pleased to see

its inclusion in the World Summit Outcome Document. R2P, I have been

told more often than I like to recall, is simply another name for

humanitarian intervention, providing a means for powerful countries,

and in particular the West, to intervene in the internal affairs of

smaller countries.

But I have to say that, even having been immunized to this extent, I

was more than a little taken back when the head of the Crisis Group

office in New York reported to me a conversation two weeks ago, in

which the head of mission of a major country in the Arab-Islamic

world said to him: 'The concept of the responsibility to protect

does not exist except in the minds of Western imperialists'.

What has gone wrong here? Why is there so much continuing resistance

to a principle which has seemed to so many others to be an important

breakthrough, capable of resolving an age-old debate in a practical

and principled way? Is there anything that we of a cosmopolitan

mindset � to pick up my earlier reference to Neelan Tiruchelvam's

extraordinarily decent, civilized and balanced approach to these

kinds of issues � can possibly do to get this debate back on the

rails and generate the kind of response that this haunting issue of

preventing genocide and mass atrocity crimes demands?

I think what we need to do is address and clearly answer four big

misunderstandings about R2P that exist to some extent everywhere,

but are particularly prevalent in the global South.

Misunderstanding One. The first is that R2P is only about military

intervention, that it is 'simply another name for humanitarian

intervention'. This is absolutely not the case, and that cannot be

said too often. R2P is above all about taking effective preventive

action � recognizing those situations that are capable of

deteriorating into mass killing, ethnic cleansing or other

large-scale crimes against humanity, and bringing to bear every

appropriate preventive response: political, diplomatic, legal and

economic. The responsibility to prevent is very much that of the

state itself, quite apart from that of the international community.

And when it comes to the international community, a very big part of

its preventive response should be to help countries to help

themselves. Paragraph 138 of the World Summit Outcome Document makes

that very clear:

Each individual State has the responsibility to protect its

populations from genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes

against humanity. This responsibility entails the prevention of such

crimes, including their incitement, through appropriate and

necessary means. The international community should as appropriate

encourage and help States to exercise that responsibility.

So does Paragraph 139 of the document, in which the world's leaders

said, again unanimously:

We also intend to commit ourselves, as necessary and appropriate, to

helping States build capacity to protect their populations from

genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity

and to assisting those which are under stress before crises and

conflicts break out.

Of course there will be situations when prevention fails, and

reaction becomes necessary. But reaction does not have to mean

military reaction: it can involve political and diplomatic economic

and legal pressure, all measures which can themselves each cross the

spectrum from persuasive to intrusive and from less to more

coercive� something which is true of military capability as well. As

the ICISS Commission insisted, 'the exercise of the responsibility

to both prevent and react should always involve less intrusive and

coercive measures being considered before more coercive and

intrusive ones are applied'.

Coercive military action is not excluded as a last resort option in

extreme cases, when it is the only possible way � as nobody doubts

was the case in Rwanda or Srebrenica, for example � to stop

large-scale killing and other atrocity crimes. But it is an absolute

travesty of the R2P principle to say that it is about military force

and nothing else.

Misunderstanding Two. The second misunderstanding, at the opposite

end of the spectrum, is that R2P is about the protection of everyone

from everything. I remember first thinking that this might become

something of a problem when a distinguished international statesman,

who had been much involved in the intervention versus sovereignty

debate in the 1990s, asked me a few months ago whether I agreed that

the international community had a 'responsibility to protect' the

Inuit people of the Arctic Circle from the consequences of global

warming! Of course, linguistically, one can argue that there is

indeed a responsibility to protect of some kind in this case � and

in the case of HIV/AIDS, or the proliferation of nuclear weapons,

and much more besides. But 'human security' is much more appropriate

umbrella language to use in these cases than 'R2P'.

To use the R2P concept in any of these ways is to dilute to the

point of uselessness its role as a mobiliser of instinctive,

universal action in cases of conscience-shocking killing, ethnic

cleansing and other such crimes against humanity: the whole point of

embracing R2P language is that it is capable of generating an

effective, consensual response in extreme, conscience shocking

cases, in a way that 'right to intervene' language was not.

The trouble is, of course, that if you stretch the R2P concept to

embrace what might be described as the whole 'human security'

agenda, you immediately raise the hackles of those who see it as the

thin end of a totally interventionist wedge � as giving an open

invitation for the countries of the North to engage to their hearts

content in the missions civilisatrices that so understandably raise

the hackles of those in the South who experienced it all before.

That trouble is compounded when it is remembered that coercive

military intervention, while absolutely not at the heart of the R2P

concept � as I have just been saying � is nonetheless a reactive

response that cannot be excluded in really extreme cases. So any

understanding of R2P as a very broad-based doctrine, which would

open up at least the possibility of military action in a whole

variety of policy contexts, is bound to give the concept a bad name.

The short point, which cannot be repeated too often, is that R2P is

not about protecting everybody from everything. It's about

protecting men, women and children from large-scale killing, ethnic

cleansing and crimes against humanity � either occurring now, or

imminently feared likely to occur, or readily capable of so

occurring if a situation deteriorates through want of effective

preventive action.

Misunderstanding Three. The third misunderstanding, and it's really

a subset of the second, is the notion that R2P is about responding

to conflict and human rights abuses generally. The problem here is

not so much R2P being stretched to deal with all the world's ills �

from HIV/AIDS to climate change � but being too indiscriminately

applied to a narrower group of those ills. But as much as people

need protection from the horror and misery of any violent conflict,

and from the ugliness of tyrannical human rights abuse, 'R2P

situations' have to be more narrowly defined.

If they are perceived as extending across the full range of human

rights violations by governments against their own people, or all

kinds of internal conflict situations, it will be difficult to build

and sustain any kind of consensus for action: we will find ourselves

rapidly back in the area of North governments worrying about how to

justify foreign entanglements where no vital national interests seem

to be immediately involved, and South governments being concerned

about their sovereignty being at risk of interventionary over-reach.

To say it again, 'R2P situations' must be seen only as those

actually or potentially involving large-scale killing, ethnic

cleansing or other similar mass atrocity crimes � situations where

these crimes are either occurring or appear to be imminent, or which

are capable of deteriorating to this extent in the absence of

preventive action � and which should engage the attention of the

international community simply because of their particularly

conscience-shocking character.

Looked at in this way, for example, Iraq at the time of the

coalition invasion in 2003 was not an R2P situation, because

although there were clearly major human rights violations continuing

to occur (which justified international concern and response, for

example by way of censure and economic sanctions), and although mass

atrocity crimes had clearly occurred in the past (against the Kurds

in the late 1980s and the southern Shiites in the early 1990s) such

crimes were neither actually occurring nor apprehended when the

coalition invaded the country in early 2003. By contrast, it would

be proper to characterize the situation in Iraq now, in July 2007,

as an R2P one, because there is every reason to fear � particularly

in the context of a precipitate withdrawal of foreign forces from

the centre of the country � that the present situation, bad as it

is, will rapidly deteriorate into massive outbreak of communal and

sectarian violence and ethnic cleansing beyond the capacity of the

Iraqi government to control, and from which it would be

unconscionable for the wider world to stand aloof.

Burundi since the early 90s is a good example of what can properly

be described as an 'R2P situation', although nobody has really

badged it as such. It is one, moreover, which has not at any stage

involved coercive military action � just a lot of hard, grinding

preventive action to ensure that the worst which everyone feared did

not in fact happen. The situation there was certainly capable of

deteriorating into the kind of large scale genocidal violence that

wracked neighbouring Rwanda, and it arguably only the intense

engagement of many international actors � including among others

Nelson Mandela with his mediation, South Africa with its troop

presence, the International Crisis Group with our analysis and

advocacy, and the new Peace building Commission with its making of

Burundi its first case � that has prevented that occurring.

Misunderstanding Four. The last big misunderstanding is that R2P

justifies coercive military intervention in every case where

large-scale loss of life, or large-scale ethnic cleansing, is

occurring or apprehended. What needs to be understood much more

clearly than it has been is that not just one criterion but multiple

criteria must be satisfied if coercive, non-consensual military

force is to be deployed within another country's sovereign

territory: it is not just a matter of saying that if a threshold of

seriousness is crossed, then it�s time for the invasion to start.

As the ICISS Commission said in its 2001 report, and the High Level

Panel in its report to the UN before the 2005 World Summit, and UN

Secretary-General Kofi Annan in his pre-Summit report, and as every

serious supporter of R2P has made abundantly clear, military

intervention for human protection purposes is a desperately serious,

exceptional and extraordinary measure, which has to be judged by not

just one but a whole series of prudential criteria.

The first of those criteria is the seriousness of the threat to

people which is occurring or apprehended: this would need to involve

large scale loss of life or ethnic cleansing to prima facie justify

something as extreme as military action. But there are another four

criteria, all more or less equally important, which also have to be

satisfied: the motivation or primary purpose of the proposed

military action (whether it was primarily to halt or avert the

threat in question, or had some other main objective); last resort,

viz. whether there were reasonably available peaceful alternatives;

the proportionality of the response; and, not least, the balance of

consequences � whether overall more good than harm would be done by

a military invasion.

Even if one stretched the threshold criterion, as to seriousness of

human rights threat, to its absolute limit in the case of Iraq in

2003, it doesn't take much analysis � even looking just at what we

knew then, not now � to generate grave doubts as to whether the

balance of consequences of an invasion could possibly be positive.

One of the many disappointments of the World Summit is that although

guidelines for the use of force of just this kind were argued for in

all the reports I have mentioned, in the hope that this would lead

to their adoption by the Security Council, they were not adopted by

the Summit � caught in a diplomatic pincer movement between the US,

who wanted no such restrictions to affect any decision to use force,

and some in the South who, I think very misguidedly, argued that to

adopt guidelines purporting to limit the force would in fact, by

recognizing its legitimacy in at least some cases, on the contrary

encourage it.

Of course no prudential criteria of this kind, even if agreed as

guidelines by the Security Council, will ever end argument on how

they should be applied in particular instances, for example Darfur

right now. But it is hard to believe they would not be more helpful

than the present totally ad hoc system in focusing attention on the

relevant issues, revealing weaknesses in argument, and generally

encouraging consensus.

While answers are readily available to all the misunderstandings I

have described, and others as well, there is no doubt that a

considerable effort of analysis and advocacy will be necessary to

keep the flame of R2P alive, and to create a global environment in

the 21st century, like no other before it, where we can be confident

that the Holocausts and Cambodias and Rwandas and Bosnias of the

past, and the Darfurs of the present, and maybe the Iraqs of the

near future, really will happen never again.

One of the efforts in which I and Crisis Group and a number of other

major global NGOs have recently been involved, and in which I hope

wonderful institutions like ICES will become involved shortly, is

putting together a project to fund and establish a new 'Global

Centre for the Responsibility to Protect', based in New York, but

with a strong North-South character and outreach, to work on just

these issues � to be a resource base and catalyst for ongoing

activity worldwide by NGOs, like-minded governments and

international organizations. Although there will be some in this

country and this region who will certainly differ, I hope there will

not be too many in this audience who would think this whole effort

misguided.

It has taken the world an insanely long time, centuries in fact, to

come to terms conceptually with the idea that state sovereignty is

not a license to kill � that there is something fundamentally and

intolerably wrong about states murdering or forcibly displacing

large numbers of their own citizens, or standing by when others do

so. Now that we have at last won recognition of that in this new

century, with the unanimous acceptance of the principle of the

responsibility to protect by the world's assembled heads of state

and government in 2005, it seems to me � and I hope to all of you

here � that it would be a tragedy now for there to be any

backsliding. I don't think there will be, but it's going to take a

lot of effort and energy from men and women of goodwill all round

the world to ensure not only that R2P continues to be accepted in

principle, but is effectively operational in practice.

This leads me to ask finally � as I guess a number of you in this

audience will have already been asking yourselves, and are about to

ask me � what has all this to with Sri Lanka, here and now? Is this

horrible, apparently intractable conflict � that took Neelan

Tiruchelvam's life, and has taken the lives of so many scores of

thousands of others � properly described as an R2P situation? And if

so, what follows from that? Whose responsibility is it to do what?

Since the resumption of hostilities last summer, both the government

and the LTTE have been careful to keep their military actions, and

their terror and counter-insurgency operations, within certain

limits. While more than 4,500 have been killed over the last 20

months, and both government and LTTE forces have repeatedly violated

international humanitarian law, the recent violence has not crossed

the boundary into mass atrocity or obvious genocide, war crimes,

ethnic cleansing, or crimes against humanity. The violence has been

contained just this side of full-scale disaster and

internationally-recognized catastrophe. We

know, nonetheless, that for those who directly experience the war it

is brutal and devastating. Hundreds of thousands � three hundred on

UNHCR's figures, two hundred on the government's � have survived the

Tiger shelling and bombing, or the government's aerial attacks and

multi-barrel rocket launchers, only to face months of constant

displacement � in jungles, in camps, or in the overcrowded houses of

family or friends.

And we know, from recent history as well as informed analysis of

present political dynamics, that there are plenty of reasons to fear

that things can get much worse, especially if the war turns from the

east to the north, as it appears may already be happening. Recent

Sri Lankan history offers all-too-many examples of large-scale

atrocities, mass graves, serious war crimes and ethnic cleansing.

And there are disturbing signs that the restraint on both sides �

such as it has been � could be eroding. The rhetoric and threats

from both sides are increasingly dire and suggest the next round of

fighting could well be extreme even by Sri Lanka's standards.

Should the war move into the LTTE-controlled areas in the north, it

is likely to be much more fierce than the recent fighting in the

east, and the impact on civilians is almost certain to be

devastating. As the war grows more vicious, it could well spill over

into areas outside the north � perhaps through deliberate attacks on

civilians designed to provoke excessive, and politically damaging,

replies from the other side. Such attacks and the communal tensions

they are sure to increase, could well lead to the further erosion of

the remaining elements of the rule of law.

All this makes it hard to argue that Sri Lanka is anything but an

R2P situation. It may not be one where large-scale atrocity crimes �

Cambodia-style, Rwanda-style, Srebrenica-style, Kosovo-style � are

occurring right now, or immediately about to occur, but it is

certainly a situation which is capable of deteriorating to that

extent. So it is an R2P situation which demands preventive action,

by the Sri Lankan government itself, but with the help and support

of the wider international community, to ensure that further

deterioration does not occur.

So what would an effective preventive strategy, featuring

cooperation between the Sri Lankan government and the international

community, actually look like? This is not the occasion for me to

offer any kind of comprehensive analysis or prescriptions, covering

all the necessary issues in all the necessary detail: we in Crisis

Group have only been here on the ground for a year, and we are still

feeling our way. And I have been talking to you, I suspect, quite

long enough already. But let me try to sketch just in outline what

in our judgment the main elements of that strategy � legal, military

and political � should involve.

First, as to the legal element. Recognizing that the government's

primary responsibility, like that of any state, is to protect all

its citizens, it must take steps to ensure that all its citizens are

accorded the equal protection of the laws. The record in this

respect leaves a great deal of room for improvement. As Crisis Group

has documented in our most recent report on Sri Lanka, there have

been hundreds of abductions, disappearances, and killings, both by

the Tigers and by security forces that are part of or linked to the

government. These have taken place with virtually complete impunity.

To date there has been only a single indictment announced for an

identifiable human rights violation committed by government

personnel.

The priority need is effective prosecutions. This means disciplining

those members of the police and security forces who are known to

have intimidated witnesses; setting up an effective witness

protection program, with active assistance from other governments

concerned with supporting Sri Lanka's justice system; providing an

adequate and independent budget to the Presidential Commission of

Inquiry headed by Justice Udalagama; and making full use of the

resources of the International Independent Group of Eminent Persons

rather than challenging its legitimacy and trying to limit its

mandate.

In a recent letter to members of the US Congress, Sri Lanka's

ambassador to the United States has rejected the need for United

Nations help in monitoring the human rights situation, while calling

rather for technical assistance to strengthen the government's

policing and judicial capacities. But these should not be either-or

options. As the recent experience in Nepal shows, UN human rights

monitoring can play an important role in supporting and developing

the state�s capacities to protect its citizen�s rights. The Sri

Lankan government should not see UN monitoring as punitive, or

invasive. Instead, it's designed to help government authorities do

their job better, in part by increasing the confidence of witnesses.

Secondly, as to the military element. The government's sovereign

responsibility is not to put its own citizens at undue risk. For

this reason, the government must resist the temptation to continue

its military campaign into the areas of the Northern Province held

by the LTTE. Here, too, the international friends of Sri Lanka have

a role to play.

Sri Lanka's conflict presents a particularly difficult situation for

would-be peacemakers in part because of the very real difficulty of

containing and taming the LTTE. Given the deliberately provocative

manner in which the Tigers attacked government forces in late 2005

and early 2006, and given their past willingness to target civilians

and the brutal nature of their rule in north, the government clearly

has legitimate security concerns to which it must respond.

Sri Lanka's international supporters can

assist the government's legitimate need to defend itself and protect

its people by strengthening the global crackdown on Tigers

fundraising, arms procurement and coercive control of the Tamil

diaspora outside Sri Lanka.

Various foreign states bear some of the responsibility for allowing the

Tigers to build up their power over the years, in part on the

misguided belief that they were a legitimate national liberation

movement.

Comment (2) by

tamilnation.org

It would seem that Mr.Gareth Evans who served as

Australian Foreign Minister for a number of years would have his

audience believe that he was unaware of something that Indian

Foreign Secretary said in 1998:

"The rise of Tamil militancy in Sri Lanka and the

Jayawardene government's serious apprehensions about this

development were utilised by the US and Pakistan to create a

politico-strategic pressure point against India, in the

island's strategically sensitive coast off the Peninsula of

India. ...Tamil militancy received support both from Tamil Nadu

and from the Central Government not only as a response to the

Sri Lankan Government's military assertiveness against Sri

Lankan Tamils, but also as a response to Jayawardene's

concrete and expanded military and intelligence cooperation with

the United States, Israel and Pakistan..."

J.N. Dixit on India's Role in the Struggle for Tamil Eelam, 1998

It's time to make amends for that by

making it harder for them to wage war and to carry out terror

attacks � by better enforcing existing restrictions on the LTTE's

ability to raise money, buy weapons and propagate its message of

violence.

All that said, and done, the probability remains, on all available

historical and analytical evidence that it is highly unlikely that

the Tigers can be defeated militarily. Some argue, however, that

while the outright defeat of the Tigers may be out of reach,

weakening them militarily would help persuade them to negotiate

seriously. It is true that some means must be found to force the

Tigers to start negotiating in a serious way, after repeated

refusals to do so over the years. But attempting to regain control

of the territory they control in the Wanni does not seem to be the

way to do this. Even assuming the Tigers can be significantly

weakened, the past thirty years teaches us that this is not likely

to encourage them to negotiate: the more probable LTTE response in

these circumstances is retreat to unconventional warfare, and

possible attacks designed to provoke government or Sinhalese attacks

on Tamil civilians.

Thirdly, as to the political element. The government's

responsibility is to seriously seek an ultimate political settlement

that is responsive to such justice as there is in the Tamil cause.

If it can work at all, the "fight now in order to negotiate later"

strategy will work only if the government is ready with a package of

political and constitutional reforms that appeal to non-separatist

Tamils and non-LTTE Tamil parties, and were at least capable of

discussion by the LTTE itself.

In the end, the only pressure to which the Tigers are likely to

respond is political pressure. This will have to be a combination of

domestic pressure � based on the two major political parties finally

coming to some consensus on constitutional reforms that address

Tamil grievances � and international pressure that limits the

Tigers' ability to raise funds to wage war and maintain their grip

on the north. International pressure on the Tigers without

corresponding political moves by the government will be ineffective

and perhaps even counter-productive, to the extent that it served to

further isolate the Tigers and push them into extremism, and drive

more moderate Tamils into their arms. At the very least, then, until

the government comes up with a constitutional offer that at least

non-separatist Tamil leaders can take seriously, there should be no

international support for offensive operations in the north.

The All-Party Conference, headed by Minister Tissa Vitharana,

provides a ready-made process through which the SLFP and parties

both within and out of government can come to terms on such an

offer. The majority and minority reports of the expert committee

offer excellent starting points for a final consensus. The

government needs to do everything it can to encourage the APRC

process, beginning with a clear public statement that the SLFP is

not wedded to its own particular proposal to the APRC and will not

veto a consensus plan that offers more extensive devolution at the

provincial level. Meanwhile, the opposition parties � in particular

the UNP � need to become active and enthusiastic members of the

process, willing to assist in the development of a meaningful

proposal that could form the basic of a lasting settlement.

I hope it will be apparent from what I have said about the R2P

principle, including how it might be applied to the present

traumatic situation here in Sri Lanka, that this is a complex,

multi-dimensional concept, which is genuinely aimed at helping

countries find their way, with international support, through

apparently intractable internal situation � and that it is simply

grotesque to describe it as a tool of Western imperialists.

I don't think Neelan Tiruchelvam, were he alive today, would have

any difficulty in grasping this. His loyalties weren�t to any

closed, static version of state or nation or community. He

understood very well what were the limits of state sovereignty, and

the nature of sovereign state responsibilities.

Comment (3)

by tamilnation.org

The peoples in the island of Sri Lanka are hopefully

becoming increasingly aware that

in the

end, it is for the Tamil people and the Sinhala people (and not

for the international community) to have a continuing, open and

honest conversation with each other and commit themselves

to secure justice and democracy - a democracy where no one

people rule another. An independent Tamil Eelam may not be

negotiable but an independent Tamil Eelam can and will

negotiate. Tamils who today live

in many lands and

across distant seas know only too well that sovereignty

after all, is not virginity.

But if the the peoples in the island of Sri Lanka are not

persuaded by all that has happened during the past several

decades, then yet again conflict resolution will take the form

of war - directed to change minds and hearts. And then the role

of symposiums and 'peace talks' - and so called

'disinterested' international intervention (which is not

transparent about its own strategic interests) may prove

m-i-n-i-m-a-l."

His central intellectual and political

struggle was to help reinvent Sri Lankan politics beyond competing

and defensive nationalisms, whether Tamil or Sinhalese, and his

perspective in this was that of a

genuine cosmopolitan, alive to the possibilities of what such a

polity could contribute to the wider world, and to what the wider

international community, provided it acted in a principled and

consistent way, could contribute to peace and stability and

development within this country.

Comment (4) by tamilnation.org

"To

those

who would advocate cosmopolitanism for

others, whilst holding fast to their own nation, that

which

Sun Yat Sen, wrote more than 80 years ago,

will serve as a continuing reminder of the political reality -

and the need to match their own words and deeds:

"At present, England and France are advocating a new idea

which is proposed by the intellectuals. What is that idea? It is an anti

nationalist idea which argues that nationalism is narrow and illiberal; it is

simply an idea of cosmopolitanism.. Cosmopolitanism will cause further decadence

if we leave the reality, nationalism, for the shadow, cosmopolitanism....

First let us practise nationalism; cosmopolitanism will follow." (The

Triple Demism of Sun Yat Sen, 1924)

A true trans-nationalism will emerge, not by

the suppression of nations but when nations flower and mature.

To work for the flowering of nations is to advance the emergence

of a true trans-nationalism. It is true that no people are an

island unto themselves. But

nationalism is not chauvinism - it becomes so only when it

takes exaggerated forms and is directed to the subjugation of

one nation by another."

Neelan's belief in the

power of words

and of ideas, his

devotion to pluralism and democracy, his

active defence of human rights and the rule of law, and his

tireless work towards a peaceful, negotiated binding of his

country's agonizingly

self-inflicted wounds, made him not only a great Sri Lankan, but

a great international citizen � whose memory we celebrate on this

day. His beliefs and principles, and his capacity to translate them

into action; have never been more sorely needed, both here in Sri

Lanka and in the wider global community. |