|

Most Western scholars and journalists have interpreted Sri Lanka as a

tropical island paradise, ruled by 2,500-year-old Buddhist ideals of peace and

compassion. Maintaining the entrepreneurial and profit-motivated capitalist

system, yet stridently pursuing non-alignment, Sri Lanka is seen as a

respectable working model of a Third World democracy, changing governments in

classic style, with modernization uniquely facilitated by superimposition of the

modern on the indigenous. Only occasionally do "race" riots and bloodshed, in

the words of Ian Jack, "stain the face of paradise". (Sunday Times, London, 18

October 1981.)

One scholar wrote: "The political system provides a better model of a

participatory democracy than many states of Europe or America ... The ethnic

minorities were preoccupied with protecting their interests against undue

domination by the Sinhalese-Buddhist majority." The Economist (London, 13 June

1981), in a special 20-page Sri Lanka: A Survey, in its desire to cater to the

world's multinationals and assure them that peace prevailed, sacrificed facts,

compromised with objectivity and even presented the rioting in Sri Lanka as one

by its Tamil community (the reverse of the truth). The opening paragraph stated:

Until 1977 it [Sri Lanka] was best known as a leading member of the

non-aligned movement; a democracy that had voted every one of its

governments out of office; a poor country that somehow avoided the harshness

of its neighbours' poverty; an island of gentle beauty marred only by

occasional riots by its Tamil minority. [Emphasis added.]

However interpreted, behind the romantic veneer and political facade lies the

reality of deprivation of basic rights to citizenship, franchise, and the

language of the Tamil ethnic nation of nearly four million people; three decades

of national oppression; military occupation; police and army repression; and,

today, a mandated Tamil genocide.

Bourgeois scholarship possessed no analytic tools to expose and come to grips

with these social conflicts. The stark unreality of this inadequate bourgeois

analysis, totally disregarding social formation, class conflict and

socioeconomic crises, was first revealed when the JVP revolution broke out in

1971.

When the seemingly secure and enduring state structure portrayed by these

scholars crumbled and virtually collapsed, when thousands of Sinhalese teenagers

resorted to armed insurrection and a revolutionary attempt to seize power to

resolve the socio-economic crises generated by the reactionary policies of the

ruling class, bourgeois scholarship was baffled. Similarly, these scholars have

ignored the more than three decades of national oppression of the Tamil people.

This is so even today, when national oppression has reached the most acute stage

of genocidal repression: incarceration of Tamil intellectuals, Catholic priests,

human-rights activists; and when armed revolutionary struggle for Tamil national

liberation is engaging the total energies of the degenerate bourgeois state.

From 1971 state power has been maintained only by frequent national

emergencies, by rifles and bayonets, deliberately provoked Sinhalese chauvinism,

and a servile, sycophantic state-controlled press. Chauvinism has become an

article of faith and to give it teeth President Jayewardene said in 1977: "If

the Tamils want war they'll have war, if they want peace they'll have peace."

The national question and even the legitimate struggle of the Tamils for justice

is thus denied as non est. Patriotic liberation fighters are branded as

"terrorists" and confronted by state terrorism.

In the absence of any properly grounded scholarly study and freely available

information, the facts of the Tamil national question in Sri Lanka have been

concealed from the Sinhalese, the Tamil people and the world community. Hence

this attempt to bring together the several dimensions of this struggle, which

David Selbourne has properly described as "a true national question, if ever

there was one". My analysis is grounded on materialist, historical bases in

order to expose the issue's complex historical causes and to correct grave

misconceptions surrounding it.

In a memorandum to the Constituent Assembly in 1972, the late Handy

Perinbanayagam, veteran nationalist, distinguished educationist, uncompromising

social revolutionary and unrepentant Gandhian who, in the 1920s, was the first

to admit "low"-caste people into his home, reflected the thinking of the

concerned Tamils:

The "Sinhala only" Act and the change in political climate that ushered

it in came about at a time when it seemed that Ceylon politics had outgrown

the racialist approach and that ideological alignments were taking shape

.... When "Sinhala only" was made the law of the land, not the slightest

effort was made to temper the wind to the shorn Tamil lamb. The self-esteem

of the Tamil-speaking community was trampled underfoot. The law was stark,

blunt and without any recognition of the fact that there was in Ceylon

another sizeable linguistic group to whom their language was just as vital

and precious as Sinhala was to the Sinhalese .... With the passing of the "Sinhala

only" Act, the entire Tamil community became frustrated, unreconciled and

psychologically uprooted. They despaired of human help and sought divine

aid. Pilgrimages, fasts, Yagas were resorted to .... The self-respect of the

Tamil people was more precious than national unity ... anyway there could be

no national unity as long as the Tamils and their language were condemned to

perpetual inferiority .... The Tamil-speaking people of Ceylon will never be

reconciled to an inferior status in their homeland.

Handy Perinbanayagam's organization, the Jaffna Youth Congress, in 1928, was

the first in the country to demand independence for the people of Sri Lanka. For

nearly 50 years he represented Sinhalese-Tamil unity. His commitment was so

strong and his politics so principled that he declined the FP's nomination as

its candidate in three elections to parliament in the 1950s and 1960s; standing

as an independent he lost each time.

He was the only Tamil to hold a clear position on the national question. I

had many private discussions with him and his forthright formulation of the

Tamil national question was that linguistic and cultural rights and equality are

of fundamental importance, and that from those spring equality between two

nations of co-ordinate status in a unitary state. He considered that ethnic and

cultural loyalties override class interests, political party or any other group

loyalty in society when a people is threatened and oppressed by another, and

that unless equality is conceded, national self-determination of the oppressed

nation would be the result. But until his death in 1977, he hoped for, and

strived to achieve, the reversal of the "Sinhala-only" law and gain recognition

of Tamil too as an official language.

The Tamil bourgeois FP and TC politicians never understood the national

question in these terms and their political discourse was so conservative and

reactionary that they alienated concerned socialist-oriented Tamils, and also

the progressive Sinhalese, by their sterile romantic demagogy and collaboration

with the conservative UNP. They possessed no political coherence and advanced no

strategies or tactics that took account of the class forces at work in the

country.

If they had shed their conservatism and sacrificed their bourgeois in

reality, petit-bourgeois - class interests, and from the beginning engaged in

revolutionary socialist struggle, the Tamil people could never have been driven

into the captive situation to which the politics of personal power brought them.

The politics of revolutionary socialist struggle were advanced by the first

Tamil Marxists, C. Tharmakulasingham and V. Sittampalam, in the mid-1930s and

early 1940s, and in the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP) at that time they were

the pioneers who correctly formulated the national question, class struggle and

the course of the proletarian revolution. They challenged G.G. Ponnambalam's

bourgeois communal politics, and Sittampalam wrote the famous tract Communalism

or Nationalism ... A Reply to the Speech Delivered in the State Council on the

Reform Despatch (1939).

The LSSP and these Tamil party leaders correctly saw the plantation Tamil

proletariat as the vanguard revolutionary force. In the mid-1940s Sittampalam

organized them for the revolutionary socialist struggle. But unfortunately, both

for the Tamils and for the revolutionary cause, Tharmakulasingham and

Sittampalam died in 1945 and 1946 respectively, and the vacuum they left was

never filled.

After 35 years, the Eelam Liberation Tigers have today come to advance the

revolutionary struggle for Tamil national liberation.

The Sinhalese politicians were never willing to concede that the state structure

agreed at independence was an alliance of the Sinhalese and Tamils to live under

one central government with equal rights. On becoming fully aware of Tamil

subjugation, and the blind alley into which the policies of Sinhalese

chauvinists and Tamil conservatives were taking the Tamil nation, in 1969 I

formed the Tamil Socialist Front, to join with any genuine socialist forces

among the Sinhalese.

Again in 1979, along with some progressive Sinhalese socialists, including

LG. Herat Ran Banda and the famous political scholar bhikkhu (Buddhist monk)

Panjaasara Thero, I launched the Podu Jana Party (Ordinary People's Party),

which stood for equal rights for the Tamils and socialist advance. But each time

it proved a Herculean task to fight the forces of reaction and the parties

floundered.

On the last occasion, as soon as the party was launched, the Prevention of

Terrorism Act was passed and President Jayewardene sent the army with a mandate,

as he put it, to "wipe out" the Tamil "terrorists" demanding a separate state.

More than 10 young Tamils were killed by the army. I was driven to the

conclusion that national oppression had reached such a level that life in a

unitary state was impossible and national unity could no longer be advocated as

a sensible political goal.

Sri Lanka, from the mid-1970s, degenerated into racist violence. Despite the

paucity of writings on the subject, the publicity by Amnesty International (AI)

of "racist" murder, detention and torture of young Tamils contributed to

international awareness of the Tamil national question and freedom struggle, The

AI report by Louis Blom-Cooper QC in 1975 stated:

. . . 42 young members of the Tamil community ... arrested for their

agitation (generally peaceful, so AI understands) for greater autonomy for

the Tamils, who feel that the provisions in the 1972 constitution regarding

language and religion discriminate against them. They had been detained

without trial under the Emergency Regulations for periods ranging from one

year to two and a half years . . .

The subsequent annual reports of A1 from 1976 on contained details of young

Tamils, often held incommunicado and tortured for their political beliefs. The

International Commission of Jurists (ICJ), stated in 1977:

It would be a pity if Sri Lanka's leadership waited for bombs to explode

and for prisons to fill up again, before conceding that the Tamils need

reassurance that they have a place in the future of the island.

The Tamil struggle for independence by secession in a separate state of Eelam

was internationalized when, in May 1979, the House of Representatives of the

State of Massachusetts passed the Eelam Resolution calling for the creation of

the Tamil state of Eelam. In 1981, several British MPs sent letters and

telegrams to President Jayewardene calling for an end to imprisonment of Tamils

without trial and for their release. Addressing the Commonwealth Parliamentary

Seminar, held in Colombo in June 1981, Jayewardene angrily reacted, in these

words:

... These telegrams and letters accuse this government of imprisoning

people without trial, even murdering them.... There is one district in our

country in which we are having some trouble with terrorists . . . I cannot

release people without trial, who have been put into jail under the normal

laws of the land. If I may say so, they are talking through their hat. When

you meet your colleagues, please tell them that I said so. [New

Internationalist, November 1981.]

Yet three months later, in August 1981, when the Sinhalese rioting against

the Tamils broke out, Jayewardene stated:

A few days ago in several estates in the Ratnapura District, estate

labourers had been subjected to violence and merciless harassment ... by, I

am ashamed to say ... people of my own race . . . I am ashamed that this

sort of thing should have happened in this country during my government.

[Ceylon Daily News, 21 September 1981.]

Because of the rioting against the Tamil people, in August 1981 the Tamil

Nadu State Assembly, in India, passed a resolution unanimously condemning the

violence and expressing sympathy with the Sri Lanka Tamils. The Hindu (Madras,

22 August 1981) reported:

The Finance Minister and Leader of the House, V.R. Nedunchezhian, who

moved the resolution, and the Leader of the Opposition,

M. Karunanidhi, and other party leaders who extended unqualified support to

it, said they did recognize the dictum that no country had the right to

interfere with the internal affairs of another nation. Where human and

minority rights were at stake, everyone had a right to demand justice, they

contended.

And the Indian Express (New Delhi, 13 July 1981) correctly summed up the

Tamil national struggle in these words:

... the cause for Eelam has picked up pace now and what it lacked in

world propaganda in the 1950s and 1960s has been effectively achieved in the

1970s and the present decade.

In all my writings, past and present, I have steadfastly held to the dictum

enunciated by C.P. Scott, editor of the Manchester Guardian for 50 years: "Facts

are sacred, comment is free." In fact, comment has been kept to a minimum, to

let the facts and events speak for themselves.

As with my previous book, in this work too I am greatly obliged to Robert

Molteno of Zed Press, my publishers, for his constant encouragement, from the

time he became aware that I was engaged in writing this book, and for his

critical assessment of the manuscript. Lastly, once again I record my

appreciation for the keen interest taken by my wife Vasantha in my writing of

this book, and for her constant pressures to get back to writing, when I had, on

the way, so often stopped writing because of my onerous duties on the Bench.

Satchi Ponnambalam London

15 July 1983

Sri Lanka is the name of the island earlier known as Ceylon. The new name was

bestowed by the Republican constitution on 22 May 1972. "Ceylon" is the name by

which the island came to be known to the outside world after Portuguese

mercantile penetration in the early l 6th Century.

To the Tamils and the Sinhalese, the indigenous people, the country had

various appellations. Its earliest name, among the aboriginal Tamils, was

Tamaraparani, the name of a river in Tamil Nadu, south India. The island is

referred to by this Tamil name in Emperor Asoka's 3rd Century BC Rock Edict in

Girnar, western India. Tamaraparani became Taprobane to the Greek travellers at

the time of Alexander the Great. The early Indian Sanskrit works refer to the

island as Lanka, its name in the Sanskrit language. The name Tamaraparani fell

into disuse by the 1st Century AD and a new Tamil name, Ilankai, came into use.

The island is referred to by that name in the Tamil classical Sangam literature

(lst-4th Century AD). And so it continued until the 1970s, when Tamil

consciousness led to the naming of the north and east of Sri Lanka, the

traditional Tamil homelands from time immemorial, as Eelam.

There has been no name for the island in the Sinhala language, then or now.

The present name Sri Lanka is its Sanskrit name, meaning "the resplendent

island". The closest Sinhala name is Sihala, used just once in the Dipavamsa and

twice in the Mahavamsa. Generally, Lanka has been the Sinhala name used. Sri

Lanka has been variously described by the early travellers. "Ceylon is

undoubtedly the finest island of its size in the world," said Marco Polo. Others

have enchantingly described it as "the pearl of the Orient", 'the pendant on the

chain of India", "this other Eden, this demiparadise", "the land without

sorrow".

Sri Lanka is situated at the southern extremity of the Indian subcontinent,

separated from it at its narrowest point by only 22 miles of sea called the Palk

Strait. It lies between six and 10 degrees north of the Equator, and on the

longitude of 79 to 81 degrees east. Sri Lanka is a medium sized island

charmingly and strategically situated in the Indian Ocean. It became a trading

post in the age of early European maritime adventure and a strategic naval base

in the age of imperialism.

The island has an area of 25,332 square miles (16.2 million acres)´┐Ż almost

the size of Ireland or Tasmania. It has mountainous terrain in the central part,

with an average elevation of 3,700 feet, surrounded by an upland area ranging

between 1,000 to 3,000 feet. The rest of the country comprises a coastal plain,

broad in the north and narrowing in the east, west and south. There is an

abundance of rivers, all starting in the central hills and flowing outwards to

the Indian Ocean. More than three quarters of the land area is arable, and the

climate is admirably suited for most tropical crops .

Sri Lanka is a country of heterogeneous culture, with two separate and

distinct ethno linguistic nations (Sinhalese and Tamils), five communities (the

Tamils of Indian origin, Sri Lankan Muslims, Indian Muslims, Burghers, and

Malays) and four great religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Christianity and Islam).

According to the last population census, at the end of 1971, Sri Lanka had a

population of 12.7 million, and it is now estimated to be about 15.5 million.

For reasons of history, the Sinhalese live in the west, south and centre, and

the Tamils in the north and east. Until the administrative unification of the

country by the British in 1833, this pattern of distribution was one of mutual

exclusiveness. This was a result of differences in language, religion and

culture and of political organisation in the past under separate Sinhalese and

Tamil kingdoms. The areas the Sinhalese and the Tamils occupied were their

traditional and exclusive homelands, to which they owed their first loyalty.

The Tamils were the aboriginal people of Sri Lanka, and, in this writer's

contention, the Sinhalese came with the introduction of Buddhism in the 3rd

Century BC. The Muslims arrived to trade from Arabia or India, or even from

Arabia via India, around the 10th Century; the Tamils of Indian origin after the

opening of plantations by the British in the 1840s; the Malays from Malaya as

mercenaries of the Dutch in the 18th Century; and the Burghers are the relic of

the Portuguese and Dutch conquest, in the 16th and 18th Century respectively.

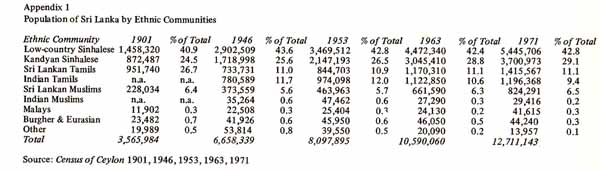

According to the 1971 census, there were 9,146,679 Sinhalese, constituting

71.9% of the population. The Sinhalese are divided into the low country

Sinhalese and the up country, or Kandyan, Sinhalese. The former comprise 42.8%

and the latter 29.1% of the population. The Tamils numbered 2,611,935, or 20.5%

of the population. The Tamils are divided into the Sri Lankan Tamils and the

Tamils of Indian origin. The former comprise 11.1 % and the latter 9.4% of the

population. The Muslims are divided into the Sri Lankan Muslims (6.5%) and the

Indian Muslims (0.2%). The Muslims are Tamil speaking. Hence 27.2% of Sri

Lanka's people are Tamil speaking. The Malays constitute 0.3% and the Burghers a

similar figure.

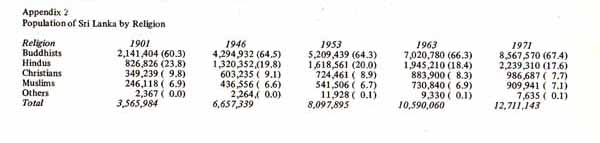

Buddhism is the ancestral religion of the Sinhalese and is professed by 67%

of the people, all Sinhalese. Hinduism is the ancestral religion of the Tamils

and is professed by 17.6%, all Tamils. Christianity is professed by Sinhalese,

Tamils and Burghers and is the religion of 7.7%; and Islam, professed by

Muslims, is the religion of 7.1% of the population.

As stated earlier, the Sinhalese and Tamils are separate and distinct

nations. Because of their particular historical past, and because of national

ethnic differences and the occupation of separate homelands, each possesses

separate and distinct national consciousness and owes its loyalty first to its

own homeland. and then to Sri Lanka.

The British were the colonial rulers of the country from 1796. Having brought

the Sinhalese and the Tamil nations together in 1833 for purposes of

administrative convenience, after a century of colonial rule and colonial

plantation economy the British withdrew at independence in 1948, leaving the two

nations yoked together under a Westminster model constitution in a unitary state

structure.

Earlier, in 1946, the Sinhalese and Tamil political elite had arrived at a

constitutional settlement for independence, the Sinhalese upper middle class

political leadership promising just and fair government and power sharing on the

basis of partnership to reap the benefits of freedom and self government. Both

the Sinhalese and Tamil leadership, in perfect amity and unity, adopted the

independence constitution as representing "the solemn balance of rights" between

the Sinhalese and Tamil peoples.

The independence constitution contained an entrenched and inviolable non

discriminatory safeguard, in Section 29(2), based on a provision in the Northern

Ireland constitution. As in Northern Ireland, it proved ineffective in

safeguarding the rights it intended to preserve inviolate. That constitution

bestowed by the British at independence, contained no law on citizenship

franchise or on individual and communal rights in a multi national state.

After independence, the Sinhalese bourgeois political leadership, via the

arithmetic of the ballot box and gerrymandering, denied citizenship and

franchise to one half of the Tamil people the million Tamil plantation workers

of Indian origin, long settled in the island. It then set half a million of them

on a course of compulsory repatriation to India, a country most of them had

never seen. The plantation Tamils of Indian origin were the largest component in

the organized working class in the country and had already engaged in working

class struggle, displayed unexpected class solidarity and voted for the Marxist

parties, who relied on them to advance their revolutionary struggle. This was

the first line of attack by the upper middle class to keep power in its hands.

The Sinhalese governments, by a policy of aggressive state financed Sinhalese

colonization and resettlement of the traditional Tamil areas, sought to end the

Tamils' exclusive occupation of their homelands in the north and east . Under

this programme, which was accelerated after 1948, over 200,000 Sinhalese

families were resettled in colonized enclaves, organized in clustered villages

in over 3,000 square miles of the Tamil homelands. As a result, one third of the

Batticaloa district in the eastern province´┐Żin the Tamil heartland´┐Żwas taken

into the new Sinhalese Amparai district. The Trincomalee district and the

Batticaloa district (reduced in size because of the carving out of the Amparai

district), formerly exclusively Tamil, were according to the 1971 census 28.8%

and 17.7% Sinhalese, respectively

Then, in violation of the policy of governments from as early as 1930 to make

Sinhala and Tamil the official languages of the country, Sinhala was made the

only official language by the government of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. The Tamils

were administered in another's language and given the oppressive stamp of a

subject people. The doors of government employment, on which the Tamils had

principally relied for employment and economic advance, were closed to them.

This forced Tamil government employees to study and work in Sinhala or leave

employment. Tamil officers were given three years to learn Sinhala or face

dismissal. This discrimination was extended to the security services, public

corporations and other services, and to the private sector, where proficiency in

the official language was an obvious premium.

Tamil parents and educationists resisted the teaching of Sinhala to their

children, although often in the past they had done so voluntarily. Now they

resisted, afraid they would lose their separate national ethnic identity as

Tamils and would face assimilation. Still worse was the government's decision

that children should be taught in their mother tongue: Sinhalese children in

Sinhalese and Tamil children in Tamil. This led to an anomalous situation: Tamil

children were supposedly "educated" without knowing the official language of

their country. They became alienated and could find no role outside their own

regions. Hence their patriotism was directed towards their own homelands.

The younger generation of Sinhalese and Tamils became strangers to each

other, and, to the Tamils, the unitary state became a monstrous irrelevance,

which served only to perpetuate their disadvantaged condition. In short, the

state not only failed to safeguard their interests, their language and culture,

but actively discriminated against them because of their Tamil birth. In fact,

they had no state; hence the urge to create a state, called Eelam, in their own

homelands .

From 1956, the Tamils did not participate in the government of Sri Lanka.

They were ruled by the Sinhalese. And the Sinhalese acted in their own interest,

not in the interest of the Tamils. Hence the discrimination against them in

employment and education. For the benefit of the Sinhalese, the government

introduced lower qualifying marks in the competitive examination for entrance to

the university. This eliminated competition. The merit system no longer existed.

Yet various stratagems of "standardisation", "district quotas", etc. were used

to favour Sinhalese students, thereby removing a large number of Tamil students

who had qualified for university admission.

It is these students, who were so flagrantly and unjustly excluded from

university and prevented by the state from achieving their aspirations, who are

today in the vanguard, providing the groundwork and leadership of the armed

liberation struggle for the secession of the state of Eelam.

Of the four prevailing religions, Buddhism at first became the de facto state

religion of Sri Lanka. Then the 1972 Republican constitution directed the state

to give the "foremost place" to Buddhism and to "protect and foster" it. The

1978 constitution of the Democratic Socialist Republic went further and directed

the state "to protect and foster the Bud&a Sasana", i.e. to include not only

the religious doctrine but also the Buddhist sects, monasteries and bhikkhus.

Hindus, Christians and Muslims have only private rights of worship. The argument

was advanced that, in the old Sinhalese monarchical society, the king was

advised by the Sangha. In this manner, Sri Lanka was made a theocratic state.

From independence, the Sinhalese governments totally isolated the Tamil

homelands from all economic development programmes and projects undertaken with

massive foreign aid from Western donor countries. As a result, over the last

three decades, while the Sinhalese people and their homelands have prospered and

flourished, the Tamil people and their homelands have suffered and become the

backyard colony of the Sinhalese.

There occurred four major anti Tamil "race" riots, in 1956,1958,1977 and

1981; each time the Tamil people living in Colombo and the Sinhalese areas of

the south had to assemble as refugees and withdraw to their homelands in the

north and east. The last two riots were well organized and specifically directed

against the plantation Tamils, many of whom abandoned the plantations and fled

to the north and east. Previously mute, exploited, miserable coolies in the

plantation enclaves, on resettlement they are becoming a new political force

uniting with their brethren of the north and east. This is a development of

great importance, not only for the Tamil national liberation struggle, but also

for the proletarian revolution and socialist reconstruction.

In all these riots, hundreds of Tamil people were killed, many Tamil women

raped and countless numbers of Tamil homes looted and burnt. After the 1958

riots, Professor Howard Wriggins wrote:

"The memory of these events will retard

the creation of a unified modern nation state commanding the allegiance of all

communities." It is important to remember that all these things happened despite

the fact that the Majority of the Sinhalese are Buddhists and despite the

fundamental Buddhist concepts of karma ("compassion") and metta ("universal

love").

All these methods were used by the Sinhalese rulers to avoid and divert the

class struggle, common to both the Sinhalese and Tamil oppressed and exploited

classes, fuelled by the reactionary economic policies adopted to benefit their

class and to consolidate power in their hands. So they resorted to Sinhalese

Buddhist propaganda. Their objective was to let national ethnic forces divide,

contain and smother class forces.

We shall see how the working class was betrayed, in crucial revolutionary

Situations, by its leaders, who were of the same social class as the rulers and

by their "Marxist" parties, because they could not advance a revolutionary

Proletarian programme. Since the leaders betrayed them, the proletariat failed

subsequently in its historic task of fighting the oppression of the Tamil nation

and supporting their right to self determination. I shall come to these matters

shortly, when I deal with the national question.

Hence the goal of the Sinhalese ruling class, pursued and consummated within

a relatively short period of ten years, was to achieve the conquest of the Tamil

nation and its lands by the force of majority legislative power, executive

edicts, military repression to quell peaceful political protest, anti Tamil

rioting and state financed colonization. To these have now been added frequent

states of emergency, the Prevention of Terrorism Law and "Tiger" hunting to

maintain that conquest.

As a result of the reactionary economic policies of the ruling class, the

dependent capitalist agro export economy has been in continual decline and

perennial crisis. Whenever it is about to sink, it is kept afloat by foreign

aid, IMF loans and World Bank organized "Paris Club" Aid Consortium commodity

import credits. The conditions for these included the devaluation of the rupee,

cuts in welfare expenditure, removal of food subsidies and a general willingness

to transfer the accumulating burdens on the poor. At the same time, to benefit

the rich, both local and foreign, the government encourages an "open economy",

liberalised imports, removal of exchange controls, incentives for foreign

capital, tax holidays, constitutional guarantees for foreign investors, etc.

Yet, after 30 years of this type of policy, the economy today is in its

deepest crisis ever. Sri Lanka, two years ago held out as the "IMF's success

story", is today yet another "IMF disaster". While heaping the burdens on the

poor, President Jayewardene stated in 1983:

The recent spate of price increases and revision of the Rupee

against the dollar in Sri Lanka were the result of the requests of the IMF . .

. the increased price of essential commodities, including rice and bread as

well as transport fares, were necessary to obtain an Extended Fund Facility

from the IMF to tide over the precarious balance of payments situation'.

The revolutionary pressures are contained by frequent states of emergency.

Power frequently alternates between the political and the military. When it gets

power, the military is not accountable to the politicians. The only connection

is the family ties linking the two´┐Żat the top. But at the bottom, for soldiers

and people, there is the same stark reality of brutality and suffering. This

structure is maintained by guns and by a servile and sycophantic press. But the

class question is about to come to the surface, as the national question already

has done, in the form of revolutionary armed struggle for national liberation.

We have seen that national oppression of the Tamils started in the very first

year of independence, with the enactment of the Citizenship Act of 1948, which

denied a million Tamils their basic right to citizenship, rendering them

stateless. This was followed by their disfranchisement the following year.

We have also seen how national oppression then extended to the Sri Lankan

Tamils. The denial of their language rights seriously affected their political,

economic, social, educational and cultural life. We have also seen how their

lands were colonized and taken over by the Sinhalese. We have also seen how

there were riots against them, and how both the Sri Lankan and the Indian Tamils

were driven to their homelands. We have seen how life in a unitary state was

made impossible and irrelevant to them. We have seen that, in reality, the

Tamils had no state to protect and advance their interests. In that context,

what was obviously and urgently needed was their own state, comprising their

homelands in north and east Sri Lanka. The United States Declaration of

Independence in 1776, in a similar situation, stated:

We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created

equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable Rights

that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving

their just powers from the consent of the governed. That whenever any Form of

Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to

alter or abolish it, and to institute a new Government, laying its foundation

on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall

seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. . . When a long train

of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object, evinces a

design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their

duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future

security . . . and such is now the necessity which constrains them to alter

their former Systems of Government.

For about a quarter century, the Tamil people and their bourgeois nationalist

leaders attempted peaceful political dialogue, non violent agitation and behind

the scenes negotiations, and they entered into open or secret pacts with their

Sinhalese counterparts to win recognition for Tamil as an official language or,

as an alternative, regional autonomy. They even collaborated to win tangible

concessions to soften the rough edges of their deprived status.

But each time pacts were broken, laws and regulations were not implemented,

and they could not win a single concession. The Tamil people were second class

citizens even in their own homelands. They were given their children's birth

certificates, their land titles, their tax certificates, their passports, in Sinhala. Mrs Bandaranaike, as prime minister from 1960 to 1964 and from 1970 to

1977, set her face resolutely against any political accommodation or modus

vivendi. In 1964, she said that the Tamils "must accept" the place that she had

allotted them. In the 1970s, with a six year emergency in force, her army

resorted to institutionalised repression of the Sri Lankan and Indian Tamils and

the Tamil speaking Muslims. Her Republican constitution removed the meagre

safeguards against discriminatory legislation contained in Section 29(2), and

the Tamils were reduced to their lowest position since 1948.

Because of the level of oppression, secession became the inevitable political

goal of the Tamils, and at their insistence the Tamil bourgeois nationalist

leaders formed the Tamil United Front (TUF). In 1975 its leader Chelvanayakam

declared secession to be the goal of the Tamil people. In 1977, the TUF was

Reformed as the Tamil United Liberation Front (TULF), and in the subsequent

general election asked the Tamil people for a mandate to secede as the separate

State of Tamil Eelam. The TULF stated in its election manifesto:

The Tamil nation must take the decision to establish its

sovereignty in its homeland on the basis of its right to self determination.

The only way to announce this decision to the Sinhalese government and to the

world is to vote for the Tamil United Liberation Front.

What the TULF was asking, in terms of the national question, was a plebiscite

on secession. The people understood it as such and overwhelmingly expressed

their collective national will to secede. They expressed, through the democratic

political process, their thirst for self determination. This was their answer to

a quarter century of national oppression. It was thus the task of the leadership

to translate that will into reality.

This was a turning point. The Tamils no longer wanted to live in union with

the Sinhalese but decided to organize themselves as a political state, separate

from them. The historic significance of this decision was that the union,

devised for the Sinhalese and the Tamils by their British overlords in 1833, had

failed to be satisfactory or workable, after 115 years of British rule and 30

years of independence.

There was an important political dimension to this decision to seek

secession. This was the role of young Tamils in the 1977 election. They had

become the worst sufferers because of the "Sinhala only" law, their educational

disadvantages, the employment impasse, the economic stagnation of the Tamil

areas and other forms of national oppression.

From 1972, they were subjected to

arbitrary arrests, and often to beatings by the police, whenever they protested

against the various discriminatory measures employed by the United Front

government to shut them out of the university, and whenever they organized black

flag demonstrations against visiting ministers. These led them to form

themselves as the "Tigers" to oppose and resist national oppression.

They were

the leading force behind the TULF's decision to secede. In fact, the TULF had

simply to endorse their position, because theoretically, as we shall see, they

had become familiar with Marxism-Leninism and with all of Lenin's tracts on the

"Right of [Oppressed] Nations to Self Determination".

Just as in the 1970 election the young Sinhalese JVP had campaigned and

secured victory for the United Front coalition, principally because of the UF's

socialist programme in the Joint Election Manifesto, in the 1977 election the

young Tamil "Tigers" campaigned and secured victory for the TULF, principally

because of the TULF's programme for secession.

In the 1970 election, for young JVP supporters, unemployment, the high cost of living and income disparities

were predominant issues which needed resolution, in the 1977 election, for the

"Tigers", national oppression, questions of education, employment, language

rights, cultural discrimination, Tamil self respect and other aspects of the

national question were the key issues.

Because of the role of young Tamils, the TULF won all 10 seats in the Jaffna

peninsula, where it received 71.8% of the votes. Jaffna is the heartland and

the intellectual capital of the Tamils, and such an absolute victory on the

question of secession was decisive. Jaffna had given the lead in all political

and social questions among the Tamils since political unification in 1833. The

TULF won the four other seats in the northern province mainland, and in the

eastern province it won Trincomalee, Batticaloa (lst member), Paddirippu and

Pottuvil (2nd member). The young Tamils were active mainly in the peninsula and

in the important town constituencies of the eastern province. The results

indicated that they had won a "yes" vote in a democratic referendum. They were

aware that Lenin had described the referendum as follows:

The right of nations to self determination implies exclusively the

right to independence in the political sense, the right to free political

separation from the oppressor nation. Specifically this demand for political

democracy implies complete freedom to agitate for secession and for referendum

on secession by the seceding nation [emphasis added] .

That the young Tamil "Tigers" based their ideology and strategy for national

liberation on Marxism Leninism and Lenin's theses could be seen in Towards

Socialist Eelam, a popular theoretical work published in Tamil by the

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, in 1980. This book is a Marxist-Leninist

analysis of national struggle and class struggle and of the proletarian

revolutionary strategies to be advanced concerning the Eelam national question.

The second part of the book explains the failure of the young JVP revolution of

1971.

After 1977, legalized national oppression of the Tamils became the goal of

the Sinhalese governments. The Proscribing of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil

Eelam Law was passed in 1978, and the following year, it was repealed and

replaced by the Prevention of Terrorism Act, the most draconian law ever to

enter the statute book of Sri Lanka. This law did not define "terrorism" and

treats every Tamil who commits "any unlawful act", at home or abroad, as a

"terrorist" liable to be detained by the police for 18 months without trial. It

authorized hitherto unknown powers of entry, search, seizure and interrogation,

including keeping the arrested incommunicado by the police.

The provisions of this act clearly violate the UN Universal Declaration of

Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. It

has been condemned by the International Commission of Jurists and its repeal has

been called for by Amnesty International.

Immediately after the passing of this act, a state of emergency was declared

in the Tamil areas on 11 July 1979, and President Jayewardene dispatched one of

the four battalions of the Sri Lanka army to Jaffna, with a mandate, in his own

words, to "wipe out" the "terrorists" demanding secession. More than 10 Tamils

were arbitrarily arrested in their homes on the very first day, and the bodies

of two of them´┐ŻInpam and Selvaratnam´┐Żwere put on public display.

As a member

of a delegation of MIRJE, a human rights organization, I subsequently

interviewed the families of both and received first hand reports of how the army

and police had come in, in civilian dress, and requested them to come to the

gate of their houses and had taken them away for no known reason.

The army then resorted to arbitrary arrests of innocent young Tamils,

detained them and engaged in systematic torture. David Selbourne, of Oxford

University, poignantly described the torture the young Tamils were subjected to

by the Sinhalese army in an army camp in the Tamil area:

The torture of Tamil detainees at Elephant Pass´┐Ż"if they groan and

cry there (Aiyu, amma, amma!) [unbearable, mother, mother!], no one can hear

them´┐Żand at the Panagoda army camp is now a routine matter. And with a high

turnover of short term detentions´┐Żin which young Tamils are taken in, often

repeatedly, for interrogation and a beating, and then released´┐Żan estimate of

numbers is difficult. There have been a few Argentinian style "disappearances"

also . . .2

In November 1982, repression was for the first time extended to Tamil

intellectuals and Catholic priests. The only law that has been applied to the

Tamil people by the Sinhalese government from the time of the 1979 declaration

of the state of emergency, is the Prevention of Terrorism Act. And, according to

the scope of this act, every Tamil is a possible "terrorist". The armed

patriotic resistance offered by the "Tiger" movement will be dealt with in

Chapter 6.

The Tamils differ from the Sinhalese in language, religion, culture, customs

and traditions. The Sri Lankan Tamils are a separate nation with their Tamil

language, Hindu religion, Tamil Hindu culture and heritage, and a history of

independent political organisation, in separate sovereign kingdoms m the north

and east, for centuries. Equally, the Sinhalese are a separate nation with their

Sinhala language, Buddhist religion, Sinhalese Buddhist culture and heritage and

history of monarchical rule, in a number of Sinhalese kingdoms in the west and

central areas, for centuries.

The fact that they are two ethnic nations is beyond dispute. As late as 1799,

Sir Hugh Cleghorn, the first Colonial Secretary of Ceylon, wrote in the famous

"Cleghorn Minute":

Two different nations, from very ancient period, have divided

between them the possession of the island: the Sinhalese inhabiting the

interior in its Southern and Western parts from the river Wallouve to that of

Chillow, and the Malabars [another name for Tamils] who possess the Northern

and Eastern Districts. These two nations differ entirely in their religions,

language and manners.

Both the Sinhalese and the Tamils were subjugated in battle by the Portuguese

at different periods. The Portuguese, then the Dutch and until 1833 the British

ruled the Sinhalese and Tamil areas as separate domains. In 1833 they were

brought together by British fiat. During the colonial period, they lived in

"union but not unity" (to borrow Dicey's phrase describing the relations between

the French speaking and English speaking Canadians). The two peoples lived in

concord and discord, amity and enmity, but were held together by a common

master, a common language and an impartial rule .

The important fact is that, in the colonial period, they co operated and

combined and yet retained their freedom to live their own life, without let or

hindrance. That Tamils and Sinhalese had an equal share in the national

patrimony was accepted as axiomatic. But a strong common national bond with a

common culture, traditions, heroes and saints, and a common national ideology to

hold the two nations together, failed to develop.

This was the case even at a time when, except at the level of the elite, the

social organization of both Sinhalese and Tamils was basically non competitive

and non acquisitive. Social emphasis was not on the individual but on the group,

the village community. Progress or success was not the aim, and both groups, as

we know today, suffered. Both were basically peasant agriculturists and the

activities of the government did not touch them. The caste society of both

provided considerable social cohesion, as each caste group was functionally

related and dependent on the other.

All these no longer exist and competitiveness for scarce resources, and

acquisition of wealth and influence, have become the objectives of a bourgeois

society. These could have been held in check, or even satisfied, by a properly

organised socialist society, but that was not what the ruling class wanted. The

upper class, and its middle class allies, have, by their policies and

propaganda, brought about the break up of the nation. These developments must be

fully appreciated before we proceed to formulate the national question. In their

act of self determination, through the democratic referendum of 1977, the Tamils

expressed their collective desire to secede. It was a historic democratic

decision but the Sinhalese political leaders were unwilling to concede the right

of self determination, in the sense of its secession and political independence.

The UNP, in its election manifesto of 1977, had

The United National Party accepts the position that there are

numerous problems confronting the Tamil speaking people. The lack of a

solution to their problems has made the Tamil speaking people support even a

movement for the creation of a separate state. In the interest of national

integration and unity, so necessary for the economic development of the whole

country, the Party feels such problems should be solved without loss of time.

The Party, when it comes to power, will take all possible steps to remedy the

grievances in such fields as (1) Education, (2) Colonisation, (3) Use of Tamil

language, (4) Employment in the Public and Semi Public Corporations. We will

summon an all Party Conference as stated earlier and implement its decisions.

Yet when it came to power, with a five sixths majority, it betrayed its

pledge to the people, both Tamils and Sinhalese, and took no action to solve the

problems of the Tamil people. Hence, it is reasonable to assume that the 35 year

old subjugation of the Tamils will continue.

President Jayewardene demonstrated this when, in October 1982, he told David

Selboume:

"They can't separate, and what we give them can't be different from

any other part of the country."

This clearly showed that he had no comprehension

of the national question. It also showed that the "Tigers" were right in their

belief that there would be no peaceful, political resolution of the national

question.

Hence, to achieve secession, the Tamil nation was left with no alternative

but armed struggle. Basing themselves on Marxist Leninist theory, the patriotic

Eelam Liberation Tigers viewed the Tamil national question, and their armed

struggle, in terms of Lenin's theoretical analysis. In a letter to Prime

Minister Premadasa, released to the local press, foreign high commissions and

and embassies, the Liberation Tigers declared on 20 July 1979:

The most important factor that we wish to state clearly and

emphatically is that . . . we are revolutionaries committed to revolutionary

political practice. We represent the most powerful extra parliamentary

liberation movement in the Tamil nation. We represent the militant expression

of the collective will of our people who are determined to fight for freedom,

dignity and justice. We are the armed vanguard of the struggling masses, the

freedom fighters of the oppressed. We are not in any way isolated and

alienated from the popular masses but immersed and integrated with the popular

will, with the collective soul of our nation.

Our revolutionary organisation

is built through revolutionary struggles based on a revolutionary theory. We

hold the firm conviction that armed resistance to the Sinhala military

occupation and repression is the only viable and effective means to achieve

the national liberation of the Tamil Eelam. Against the reactionary violence

and terrorism perpetrated against our people by your Government we have the

right of armed defence and decisive masses of people are behind our

revolutionary struggles. [The full text of this letter appears as an

Appendix.]

We have seen that the principal factor that generated the demand for

secession is national oppression by the big Sinhalese nation of the small Tamil

nation. Theoretically, Tamil nation, as an oppressed nation has the right to

self determination, and on the basis of a democratic referendum resolved upon

secession. Some self styled Marxists in Sri Lanka, lacking in theoretical

clarity, while conceding that the Tamil nation as an oppressed nation has the

right to self determination contend that self determination does not include

secession. The correct theoretical position has been precisely and clearly

stated and restated by Lenin that self determination of nations is nothing but

secession and the formation of an independent state. To clear up the theoretical

muddle it is necessary to quote some passages from Lenin:

Self determination of nations in the Marxist programme cannot,

from a historico-economic point of view, have any other meaning than political

self determination, state independence, and formation of a nation state'

(Lenin: The Right of Nations to Self Determination)

Again, Lenin formulated:

Consequently, if we want to grasp the meaning of self

determination of nations, not by juggling with legal definitions, or

"inventing" abstract definitions, but by examining the historico economic

conditions of the national movements, we must inevitably reach the conclusion

that the self determination of nations means the political separation of those

nations from alien national bodies and the formation of an independent

national state'.

Lenin advanced the freedom of an oppressed nation to secede as a universal

socialist principle of workers' democracy. He viewed the struggle of an

oppressed nation to secede as a revolutionary mass action and a necessary part

of the proletarian attack on the bourgeoisie. In the case of the Tamils too,

since their historic decision in the 1977 elections, the struggle for secession

needs historical fulfilment, and the revolutionary struggle advanced by the

Eelam Liberation Tiger Movement has been on the basis of socialist democracy and

proletarian revolution. Hence it is a classic and authentic attempt to resolve

the national question, and one that is sui generis and needs to be supported by

all freedom lovers, liberationists, Tamil patriots and genuine Marxist

Leninists.

One last point needs to be adverted to. Many readers may be left with the

question as to how in the face of such genocidal repression by the state terror

machine secession could be achieved and the Eelam state established. I could do

no better in answer than refer to Lenin, again:

Under no circumstances does Marxism confine itself to the forms of

struggle possible and in existence at the given moment only, recognizing as it

does that new forms of struggle, unknown to the participants of the given

period, inevitably arise as the given social situation changes." (Collected

Works, Volume 11, p. 213)

References

1. In the appendix to the Tamil book Towards Socialist Eelam, all Lenin's

writings on the self determination of oppressed nations are cited, without a

single exception

2. David Melbourne, in The Sinhalese Lions and Tamil Tigers of

Sri Lanka in

The Illustrated Weekly of India, Bombay 17 and 24 October 1982.

Sri Lanka presents a rich diversity of peoples and cultures, some ancient and

indigenous, others modern and transplanted. From the early centuries of its long

history, Sri Lanka has been a diverse society, the components of diversity being

ethnicity, language and religion. l The island's geographical proximity to India,

its strategic location on the east west sea route and the mercantile and

territorial encroachments of the European powers contributed to the ethno

linguistic and religious make up of the country.

Every great change that swept India had its repercussions in the island and,

until the beginning of the 16th Century, Sri Lanka was a pawn in the power

struggles of the south Indian Tamil kingdoms of Pandya, Chola and Chera. During

the four and a half centuries of European rule, beginning with the Portuguese

conquest of maritime areas in 1505, the elements of diversity have kept

increasing. And by the time of the British conquest, in 1796, the island had

acquired its multi ethnic structure, the two well developed ethnolinguistic

cultures of Sinhalese and Tamil, and the four great religions of Hinduism,

Buddhism, Christianity and Islam. While the island as a natural geographical

unit imposed a certain unity on the people, their diverse cultures, which are a

residue of history, dictated separate collective identities and solidarities.

The outstanding fact of Sri Lanka's nationality structure is that, from

ancient times and continuously over the last two millennia, two major ethnic

people´┐Żthe Sinhalese and the Tamils´┐Żhave lived in and shared the country as co

settlers This shared descent is traceable to the 2nd Century BC. The history of

the people before that time has not been unravelled on a valid historical basis

and is wrapped up in myths and legends invented by the Pali chronicles of the

Sinhalese´┐Żthe Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa´┐Żwritten in about the 4th and 6th Centuries

AD, respectively.

Both these chronicles are verse compositions in Pali, the

Buddhist scriptural language, written by Buddhist monks, not in the historical

tradition but as being the words of Mahanama, the author of Mahavamsa, "for the

serene joy and emotion of the piously They were written unabashedly from the

Sinhalese Buddhist Standpoint, lauding the victories of the Sinhalese kings over

the Tamil kings, treating the former as protectors of Buddhism and saviours of

the Sinhalese, While deriding the latter as invaders, vandals, marauders and

heathens.

In an effort to establish that the Sinhalese are the original occupiers of

the island, the chronicles misrepresent the aboriginal Nega and Yaksha (or

Raksa) Tamil people as non humans, and validate their version by creating myths

about the past. yet these chronicles and their stories have been relied upon by

historians for the reconstruction of the early history of the island, and this

mythological history has been retold in later Sinhalese historical and literary

works, and repeated in the Buddhist rituals, so that they constitute the current

beliefs of the Sinhalese. They exert a direct influence on present day ethnic

relations in Sri Lanka. As Walter Schwarz, a perceptive writer on the national

question in Sri Lanka, has observed: "The most important effect of the early

history on the minority problem of today is not in the facts but in the myths

that surround them, particularly on the Sinhalese side."2

It is not established on valid historical grounds when and how the Sinhalese

emerged as an ethnic people in the country. There exists no historical evidence

for a Sinhalese presence before the 2nd Century BC. The place of evidence has

been taken by the Vijaya legend, invented by the authors of the chronicles. The

Dipavamsa, literally "The Story of the Island" (probably written in the 4th

Century AD), purports to narrate the story of the island from the earliest human

times.

It introduces Vijaya, as the first occupant and founder of the Sinhalese, in

these words: "This was the island of Lanka called Sihala after the lion. Listen

to this chronicle of the origin of the island which I narrate." According to the

chronicle, Vijaya, the grandson of a union between a petty Indian king and a

lioness, on being banished for misconduct by his father Sinhabahu (the lion

armed), came with 700 men by vessels and landed on the west coast of Lanka, at a

place called Tambapanni, in 543 BC, on the day Buddha died, i.e. passed into

nibbana. Vijaya's men were lured into a cave and captured by a demoness (Yaksha)

queen named Kuveni. Vijaya rescued his men, married Kuveni and had a son and

daughter.

Vijaya later told Kuveni that before being crowned king of Lanka he should

marry a human princess. He therefore banished Kuveni and the children into the

jungles, sent his ministers to the Tamil king Pandyan, who ruled the Madurai

kingdom in south India, and took the king's daughter as his wife. His men also

obtained their wives from the Madurai region. Kuveni was later killed by the

demons. In the jungles, the children married incestuously and had many children,

from whom, the chronicle states, the Veddas3 of Sri Lanka arose.

Vijaya is said to have held his coronation and made himself the king of Lanka

and ruled for 38 years from Tambapanni, his capital. He and the Tamil princess

had no children and hence, on his death, his brother's son Pandu Vasudeva came

from Bengal and became the king of Lanka. This story has been re told with

greater embellishment in the Mahavamsa, literally "The Story of the Great Dynasty" (written in the 6th Century AD), the source

of the present day early history of Sri Lanka.

There is no historical evidence whatsoever for the arrival of Vijaya and the

related story. There is no trace of a place named Sinhapura or of the petty king

Sinhabahu in Bengali history. But because of their inability to account

historically for the emergence of the Sinhalese, historians follow the lead of

the Vijaya legend.4 Thus K.M. de Silva, Professor of History at the University

of Sri Lanka, states:

Both legend and linguistic evidence indicate that the Sinhalese

were a people of Aryan origin who came to the island from Northern India about

500 BC. The exact location of their original home in India cannot be

determined with any degree of certainty. The founding of the Sinhalese is

treated in elaborate detail in the Mahavamsa with great emphasis on the

arrival of Vijaya (the legendary founding father of the Sinhalese) and his

band in the island.5

On the basis of this legend, the present day Sinhalese claim that they are

the first settlers and are of Aryan origin. The foremost propagandist of the

Sinhala Buddhist "revival", Anagarika Dharmapala, wrote in 1902 on the origin of

the Sinhalese:

Two thousand four hundred and forty six years ago a colony of

Aryans from the city of Sinhapura in Bengal . . . sailed in a vessel in search

of fresh pastures . . . The descendants of the Aryan colonists were called

Sinhala after their city Sinhapura, which was founded by Sinhabahu the lion

armed king. The lion armed descendants are the present Sinhalese .6

The chronicles introduce the mythical Vijaya and his men as the first

settlers and proceed to misrepresent the settled Tamil Naga and Yaksha people as

non humans. The former are described as "snakes" and the latter as "demons".

This has also been uncritically repeated by modern historians according to whom

the Nagas and Yaksha are non humans of prehistoric times .

But it is an undeniable fact that, in the proto historic period of the island

to (c.1000-100 BC), there were two Naga kingdoms, one in the north called Naga Tivu

in Tamil, and called Naga Dipa in the Indian Sanskrit works, and the other in

the south west, in Kelaniya. Even the Pali chronicles mention them in a

different context, in connection with the purported visits of Buddha to the

island. The Mahabharata and Ramayana, the two great Indian epics written in

Sanskrit before the 6th Century BC mention the Naga kingdoms and their conquest

by Ravanan, the Tamii Yaksha king of Lanka. So does the Greek astronomer and

geographer Ptolemy, writing in the 2nd Century AD, who locates Naga Dipa in the

north, covering the territory from Chilaw in the west to below Trincomalee in

the east.

According to tradition, the Tamils of India and Sri Lanka are the lineal

descendants of the Naga and Yaksha people. The aboriginal Nagas, called Nakar in

Tamil had the cobra (Nakam, in Tamil) as their totem. The Hindu Tamils, to this

day, continue to worship the cobra as a subordinate deity in the Hindu pantheon

and there are many temples for the cobra deity all over north Sri Lanka.7

Equally, the Yakshas were not demons but worshippers of demons, as shown by the

still prevalent practice among the Hindu Tamils of propitiating the demons,

which arose out of primitive fear and belief in the destructive power of demons.

Ptolemy describes the Tamil Yaksha people:

"The ears of both men and women

are very large, in which they wear earrings ornamented with precious stones."

The wearing of ear rings by both men and women is a custom still extant among

the Tamils in the villages of north Sri Lanka and in south India, and the poor,

unable to purchase gold ear rings, wear rolled palmyrah leaves instead. That the

ancestors of the present day Tamils were the original inhabitants of Lanka is

well brought out by the historian Harry Williams:

"Naga Dipa in the north of Sri

Lanka was an actual kingdom known to historians" and "the people who occupied it

were all part of an immigrant tribe from South India´┐ŻTamil people called

Nagars".8

Another writer states: " . . . long before the coming of the Sinhalese

there would have been long periods when the island was inhabited by the

ancestors of the present Tamil community".9

Recent archaeological excavations of burial mounds in the old Naga Dipa area,

which covered a region from Chilaw up to Trincomalee through Anuradhapura, have

shown skeletal remains of a people of megalithic culture who practised

inhumation as a mode of burial in the proto historic period. The artefacts found

within, such as rouletted pottery with graffiti symbols, iron nails, bronze seal

rings, arrow heads, spears and daggers, show that those people had a settled and

civilized life. The Sangam literature (lst- 4th Century AD), reflecting the

indigenous cultural tradition of the Tamils of south India, mentions inhumation

as a custom then prevalent. These finds have, on paleographical reckoning, been

dated to not later than the 4th Century BC 10 and the skeletal remains classified

as those of south Indian type.11The north western urn burial site (Pomparippu)

is said to offer many parallels with those found on the Coromandel coast of

Tamil Nadu, south India. 12 Ptolemy refers to Naga kingdoms on the Coromandel coast, and towns with

toponyms like Nagar Koil and Naga Patinam, appearing from the earliest times,

confirm that Naga people of the same origin occupied the Tamil areas of south

India and Sri Lanka. The latter may have migrated from south India in early

times, when Sri Lanka was certainly joined to mainland India through the shallow

ridge of sandbanks called Adam's (or Rama's) Bridge in the Gulf of Mannar.

Furthermore, the important find of a statuette of Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of

good fortune, in the Anaikoddai excavation (1982) confirms other evidence that

the Naga people were Hindus and that Hinduism was the religion of the people of

Sri Lanka before the introduction of Buddhism.13

The conclusions that could validly be drawn from the new historical data

clearly establish that the ancestors of the present day Tamils were the original

occupiers of the island, long before 543 BC, which the Pali chronicles date as

the earliest human habitation of Sri Lanka.

How, then, does one explain the emergence of the Sinhalese as an ethnic

entity in the island? In the 3rd Century BC (the date usually assigned is 247

BC), Buddhism was introduced into the island by missionaries led by Bikkhu

(Buddhist monk) Mahinda, possibly the son of Asoka, the great Emperor of India

(c 273 - 232 BC), who became converted to Buddhism and was determined to spread

the religion far and wide.

Devanampriya Theesan the Tamil Hindu king of Lanka at

that time, accepted the missionaries from Asoka and became converted to

Buddhism. Since, in those days, the religion of the ruler became the religion of

the people, and because Hinduism has always been infinitely flexible and little

given to rigorous dogma, Buddhism, being an offshoot of Hinduism, spread fast in

the island.

Mahinda brought not only the religions message but also the Pali canon, i.e.

the scriptures as preached by Buddha in Pali, a language of Aryan people who

overran India in ancient times, driving the Dravidians´┐Żthe pre Aryan people of

north and central India´┐Żsouthwards. The Buddha dhamma (the doctrine comprising

the moral order), or at least the basic "five precepts" were taught to the

people in Pali, and they are still recited by the Buddhists in Pali. The Sangha

(the order of Buddhist monks), whose prerogative it was to know and preach the

doctrine, learnt Pali in order to understand the dhamma as well as the Vinaya

(rules of discipline for the Sangha). In this way, with Buddhism came Pali, a

new language, and it was learnt by the bhikkhus to preach the dhamma as well as

for the writing of books, just as Latin was used by the Christian clergy in

medieval Europe.

In the course of time, the Sinhalese language as well as the alphabet and the

script grew from the Pali language. With the spread of Buddhism and the growth

of the Prakritic Sinhalese language, there occurred a religio linguistic

division of the people into those who remained Hindu Tamils and the emergent

Buddhists speaking the Sinhalese language. This development can be inferred from

a number of Sinhalese Buddhist features in Sri Lanka. Firstly, there is no

evidence whatsoever of the Sinhalese as a people, or of Sinhala as a language,

before the introduction of Buddhism in 247 BC. The earliest cave inscriptions are

in the same Brahmic script as the famous Rock Edicts of Asoka in western India.

The Encyclopaedia Britannica states:

The earliest surviving specimens of the (Sinhalese) language are

brief inscriptions on rock, in Brahmi letters, of which the earliest date from

c 200 BC. The language of these inscriptions does not appear to be greatly

different from the other Indian Prakrits (i.e. chronologically Middle Indo

Aryan languages) of the time.l4

Secondly, the Sinhalese Buddhists, in the practice of Buddhism, have not

quite succeeded in freeing themselves from their Hindu past. They continue to

worship the Hindu deities, although Buddha revolted against the worship of gods

and Buddhism opposes idol worship.15

Thirdly, the caste system, the central feature of Hindu society, prevails

among the Sinhalese Buddhists, although Buddhism is opposed to caste. This again

is a vestige of the Hindu past.

These, taken together with the historical and archaeological data outlined

earlier, lead one to the irresistible conclusion that Sinhalese emerged as a

result of the ascriptive cleavage consequent upon the spread of Buddhism in the

Pali language. The Sinhalese, then, in terms of their origin, are not an Aryan

people as popularly claimed, but Tamil people who adopted a language which

developed from Pali, an Aryan dialect.

Even the pioneer Sri Lanka historian Dr G.C. Mendis, although he uncritically

accepted the Vijaya legend of the chronicles, was left in doubt about its

validity and observed:

" . . . it is not possible to state whether they [the Sinhalese] were Aryan

by blood or whether they were a non Aryan people who had adopted an Aryan

dialect as their language".16 Equally, Dr S. Paranavitana, the

former Archaeological Commissioner, stated:

"Thus the vast majority of the

people who today speak Sinhalese or Tamil must ultimately be descended from

those autochthonous people of whom we know next to nothing.''l7

There is, however, no single origin of the present day Sinhalese, as over the

centuries diverse people have merged to form the Sinhalese ethnicity. The

Tamils, living among the Sinhalese in the south, "gradually adopted the

Sinhalese language, as some of them still do in some of the coastal districts,

and were merged in the Sinhalese population''.l8

Between the 14th and 18th

Centuries, large numbers of Dravidians, mostly from Malabar, south India, came

over and settled and were assimilated as Sinhalese. So did the Colombo Chetties,

whose ancestors came from the Chettiar community, in Tirunelveli district of

Tamil Nadu, owing to a great famine there in the 17th Century.

Furthermore, in 1739, since Sri Narendrasinghe, the Sinhalese king of the

Kandyan kingdom, had no suitable progeny to succeed him, the brother of his

Tamil queen, from the Nayakkar royal dynasty in Madurai, ascended the throne and

took on the Sinhalese name Sri Vijaya Rajasinghe. This line of Tamil kings

continued until the Kandyan kingdom was ceded to the British in 1815. The kings

of the Nayakkar dynasty took on Sinhalese names and professed Buddhism to please

their subjects. So did their families, courtiers and retinue, who came over in

substantial numbers.l9

Hence, in reality, as Dr N.K. Sarkar has put it: " . . . no matter what the

racial origin, little remains of the original stock, except a belief in it".20

Broadly speaking, in terms of present day identification and self image, a

Sinhalese is one who bears a Sinhalese name and speaks the Sinhala language,

whatever his origins may be.

The Sinhalese people and the Sinhala language are found only in Sri Lanka.

The Sinhala language is the mother tongue of the Sinhalese, who are 71.9% (69.3%

in 1953) of the Sri Lankan population, today a little over 15 million. In 1953,

Sinhala was the only language spoken by 58.9%, Sinhala and Tamil by 9.9% and

Sinhala and English by 4.29 of persons three years and over. The Tamils (both

Ceylon Tamils and "Indian" Tamils) constitute 20.5% ( 22.9% in 1953) of the Sri

Lankan population. The Tamil language is the mother tongue of the Tamils and

also of almost all Ceylon Muslims (or Moors) who form 6.5% of the population,

and the Indian (or "Coast") Muslims who form 0.2%. Tamil was the only language

spoken by 21.6% and Tamil and English by 2.9% of persons three years and

over.21

The Sinhala language grew out of Pali and is not connected to the present day

Indo Aryan languages of northern India, which are all related, with varying

degrees of kinship, to Sanskrit language. The vocabulary consists basically of

Pali words with many Sanskrit and Tamil loan words. The long vowels of the Pali

words are shortened and the double consonants reduced to single ones. Dr W.S.

Karunatillake admits:

"There have been several linguistic traditions that have

exerted varying degrees of influence on the development of the Sinhalese

language. Of these Tamil is one of the most important. There is reason to

believe that in the past, the study of Tamil language and literature was

cherished by the Sinhalese scholars."22

Sinhalese is written in a variation of the Pali script, but in rounded

letters like those of the Dravidian language scripts, closely resembling Telegu

letters. In the first century AD, the Sinhalese alphabet showed a sudden

deviation from the letters inscribed in the rocks and resembled those in the

inscriptions of the Andhra kingdom, and was probably introduced from there. At

that time, Andhra was a great centre of Buddhism, with the famed Amaravati and

Nagarjunikonda, on the river Krishna. And, according to Benjamin Rowland, in his

Art and Architecture of India, the Nagarjunikonda "monasteries included one

building specifically reserved for resident monks from Ceylon".

Until the 6th Century, the Sinhalese language remained in its Prakritic

stage, and it was only by the 10th Century that the language and script