My paper deals with the construction of Tamil national

identity in the LTTE-controlled areas of north-eastern Sri Lanka. In

particular it focuses on the relevance of the new LTTE burial practices

within the process of nation building. In this context I will pay

special attention to the perception that Tamil people, both civilians

and fighters, seems to have of the Tigers� cemeteries as symbolic

centres of the new nation, the Tamil Eelam1.

In my paper I will analyse the reasons which have led to

this perception. On one side I will discuss the functional analogies

between the LTTE cemeteries and the war graveyards of military Western

tradition. On the other, I will emphasise their peculiarity of being

perceived as holy places. The Tigers� cemeteries are indeed called

Tuillum Illam, literally �Sleeping houses�, and are often portrayed as

temples. I will argue that the LTTE, in spite of their secular nature,

have decided not to reject this religious interpretation, because it

allows them to include the Tuillum Illam in the mainstream of Hindu

tradition. In this context the ability to integrate the religious

dimension represents a crucial component in the process of nation

building.

This paper draws upon findings of fieldwork I carried

out between July 2002 and January 2003 in the north-eastern regions of

Sri Lanka controlled by the LTTE.

The change in funerary practices

At the beginning of the �90s, in a Sri Lanka ravaged by

civil war, a great change in the funerary practices reserved to the LTTE

fighters took place. Until then the bodies of the Maaveraar (literally

�Great Heroes�) were cremated in accordance with Hindu tradition and the

ashes were given to the families. From that period onward LTTE began to

bury their dead and to collect them in the Tuillum Illam.

To understand the meaning of this change in ritual we

have to consider the mortuary practices which are performed in the north

and in the east of Sri Lanka. These practices depend on the religion

professed by the families of the dead. Both Christians and Muslims bury

their dead, and put the bodies in their graveyards2,

while Hindus resort to cremation and immerse the ashes in rivers, though

there are some exceptions that we will discuss later. This means that in

this context burial is not unknown, but is reserved to people belonging

to Christianity and Islam, and that most people, being Hindu, are not

accustomed to this practice. It might be argued that the shift from

cremation to burial should have been perceived as a radical move from

traditional practices, and therefore should not have been so readily

accepted.

Before discussing the strategies that are carried out by

Maaveerar�s relatives and Tamil civilians in order to accept the new

practices, I would like to illustrate the official explanation given by

the LTTE�s leadership to justify this change. When questioned about the

reasons for the shift in ritual, Mr. Pontyagam, in charge of Maaveerar�s

office, stated:

Before 1991 we burnt [the fighters] according to

Hindu rites. If the parents asked for the ashes, we gave them. But

Christians and Muslims didn�t take ashes. We had this problem. There

were Christian soldiers, and the parents didn�t want to burn them. A

meeting of the leaders was organized and they decided to study what

did for their soldiers other countries like America and England.

They saw that they used to bury their soldiers. Then they decided to

proceed in the same way [�]3.

Then, when asked about the reaction of Hindu relatives,

Pontyagam replied:

Yes, relatives agreed because they [the LTTE

leaders] explained them it was a worldwide custom. Before that there

were problems, and then they decided, Prabhakaran4

decided, what to do. Indeed if we have a look at the pictures of

Tuillum Illam, we can recognize in their structure the pattern of

Western war graveyards, particularly if we compare the Tuillum Illam

with other cemeteries in the area.

It is not surprising that the LTTE chose to adopt

funerary practices utilized by Western armies. In fact, Tigers do not

like the epithet of �terrorist� and claim the status of liberation

fighters. That is why they never miss an opportunity to emphasize that

they are a regular army: for instance, they point out that they wear

uniforms. From this perspective, an acceptance of Western military

funerary customs might be considered a logic consequence of such a

claim.

Conversely, what is really surprising is to ascertain

that the official explanation for the transition from cremation to

burial is never mentioned by civilians or fighters. Indeed, if

questioned on this issue, both tend to refer to other explanations for

the change. In the course of my fieldwork, I interviewed LTTE fighters,

Tamil civilians living in both LTTE- and government-controlled

territories, and eventually Tamils living in Italy. The persons

interviewed gave me different interpretations for the transition, but

nobody referred to the official one. This official explanation is

probably neither significant nor acceptable to Tamil civilians,

particularly for the relatives of the dead. In fact, when a daughter or

a son, a sister or a brother are given burial as opposed to the

customary ritual cremation, it is likely that relatives would not be

satisfied with an explanation that justified this practice on the basis

of conformity with Western military tradition. Indeed, it is more than

likely that they would seek other more meaningful explanations.

There are in fact two main interpretations5

which tend to emerge to justify the change in the LTTE funerary

practices. The first one emphasizes the need for remembrance, whether

the second one places the burial practice within the mainstream of Hindu

tradition.

Tuillum Illam as places of remembrance

To elucidate the process which make it possible for the

Tuillum Illam to be regarded as places of remembrance, I would like to

quote some passages from interviews I took in Sri Lanka during my

fieldwork. For instance a fighter in Vavuniya asserted: �This is a place

of memory, if you burn them [Maaveerar] the history will be destroyed�.

Similarly a man in charge of Koppai�s Tuillum Illam explained:At the

beginning we burnt them [Maaveerar]. Then we thought: �It is not nice,

it is better to have a place to remember them�. If you have a monument,

every year you can celebrate them, and the relatives can come to visit

them, they often do this.

A civilian in Jaffna affirmed: In this situation we did

need a place to make our people happy. When our children ask [showing

the Tuillum Illam]: �What is it?�, we reply: �Here there are the people

who sacrificed their life for the freedom of Tamil Eelam�.

A young Tamil man living in Italy pointed out:

The Maaveerar are people who defend the land, our

homeland. If we burn them, they become dust, and they will

disappear. To keep their memory alive, the Tigers bury them and

build tombs. They write on the tomb �This person died to defend the

homeland� and in this way they [the Maaveerar] are with us longer.

Finally the sister of a fighter fallen at Elephant Pass clarified:

�We have to preserve the [Maaveerar] bodies, at least the bones must

be preserved�.

It could be argued that to have places of remembrance it

is not necessary to have tombs. However we must keep in mind that in

Hinduism, as Maurice Bloch and Jonathan Parry stress, nothing of the

individual is preserved which could provide a focal symbol of group

continuity. The physical remains of the deceased are obliterated as

completely as possible: first the corpse is cremated and then the ashes

are immersed in the Ganges and are seen as finally flowing into the

ocean. The ultimate objective seems to be as complete a dissolution of

the body as possible (1982: 36).

Such a dissolution imply the absence of a public space

where the dead are remembered. Even if there are postcremation rituals

in which ancestors are worshipped (Knipe 1977), such rituals are

performed in the private space of the house and are carried out by

relatives. The cultural background provides reasons for the lack of any

correlation between cremation and public place of remembrance.

The perception of Tuillum Illam as place of remembrance

would also explain, according to my informants, their destruction by Sri

Lankan Army

6. M. R. Narayan Swamy, a

journalist, describes in this way the capture of Jaffna:

It is clear Prabhakaran will one day certainly try

to recapture Jaffna, whatever be the cost, if nothing else to avenge

the humiliation of 1995 when victorious Sri Lankan troops rolled

into ancient Tamil town amid frenzied celebrations across the

country. The LTTE has not forgotten the way the military destroyed

without trace the LTTE�s sprawling martyrs� graves that were spread

over a vast open ground (2002(3): 355) (italics mine).

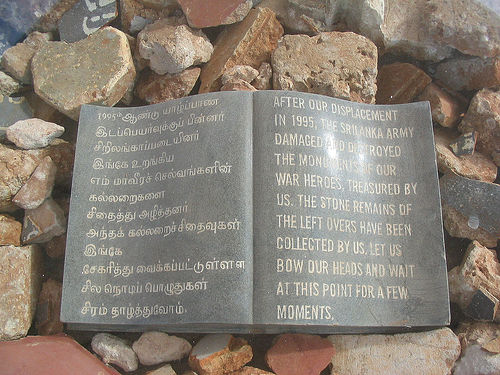

At the entrance of Tuillum Illam in Koppai and Naundil

the visitor can see, encased in glass, the collected pieces of

devastated graves and cenotaphs. A stone book has been placed on the

pieces, and the following words are impressed on it:

"After our displacement in 1995, the Sri Lanka army

damaged and destroyed the monuments of our war heroes, treasured by

us. The stone remains of the left over have been collected by us.

Let us bow our heads and wait at this point for a few moments."

The destruction of tombs by Sri Lankan Army can be

considered as evidence of governmental soldiers� appreciation of Tuillum

Illam�s significance within the Tigers� struggle. In order to better

understand the symbolic value of the LTTE�s burial grounds, we need to

pay attention to the functional analogies between such places and the

war military cemeteries of Western tradition.

Functional analogies with war cemeteries in military

Western tradition

It could be argued that Tuillum Illam share many

functions with war cemeteries of Western tradition. As George Mosse

(1990) points out, to concentrate all the dead soldiers in the same

space gives the opportunity to stress the importance of their deeds and

to focus people�s attention on their sacrifice for the nation. It is

exactly in this perspective that we may read the words of Prabhakaran

who, talking about the graves, affirms �The tombs of the fallen Tigers

heroes will be the foundation of our new nation� (quoted in the 1995

LTTE diary).

Another important function of Western war cemeteries is

their being places of commemorations, which is also the case of Tuillum

Illam. The Maaveerar are celebrated on November 27th, officially

remembered as the day in which the first Tiger died. In this day the

LTTE pay honours to their dead fighters all over the world. Tamils of

the Diaspora organize celebrations in public places such as theatres and

public halls7, while in Sri

Lanka the ceremonies take place in the Tuillum Illam.

Ceremonies start in the afternoon, when people go to

the Tuillum Illam bringing flowers, incense, camphor and candles and

stay by the tombs; women weep and cry out in pain. The Maaveerar day is

a main LTTE political event, not only because of the extensive

involvement of civilians, but also because it is the occasion in which

Prabhakaran�s yearly speech is delivered and broadcast through

loudspeakers in all Tuillum Illam. Prabhakaran�s speech is considered,

as Cheran emphasizes, �a sort of throne speech in which he usually

elaborates on the victories, ground situation, future plans and an

analysis of the current political situation� (2001: 17). In this sense

the Tuillum Illam are the setting for the exercise of �intentional

rhetorics� which, as Elizabeth Tonkin stresses, are a central element in

the processes of nation building. Indeed �Intentional rhetorics� are

utilized �to convince people of a social identity which they may not

otherwise experience as such� (1992: 130).

Eventually - to conclude the analysis of functional

analogies - in war cemeteries belonging to Western tradition there are

symbols which can be interpreted in different ways. As George Mosse

clarifies, English cemeteries were centred upon the Cross of Sacrifice

and the Stone of Remembrance. The Cross of Sacrifice, in Rudyard Kipling

words, has �a stark sword brooding in the bosom of the cross� whose

symbolism, by the Commission�s own admission, was somewhat vague. It

could signify sacrifice in war or simply the hope of resurrection [�].

The Stone of Remembrance and the Cross of Sacrifice projected a

Christian symbolism which dominated the cemetery, though originally the

Stone was conceived by its architect, Sir Edwin Lutyens, as a

non-Christian pantheistic symbol. Yet, at times, the Stone of

Remembrance was referred to simply as �the altar�, conferring the same

religious significance upon it that the Cross of Sacrifice possessed

(1990: 85).

Similarly in the Tuillum Illam the �flame of sacrifice�

burning on the central platform could be compared, as suggested by the

chancellor of Jaffna university, to the flame of the Arc de Triomphe in

Paris, but at the same time it could also be perceived as a symbolic

substitute of the fire of cremation.

Tuillum Illam as temples

I would now examine the second interpretation which

emerges from popular narrative to justify the transition in funerary

practices. This interpretation is given mainly by civilians and is

connected with the religious Hindu tradition. As already mentioned, in

Hinduism there are some exceptions to cremation. In the context of the

Sri Lankan civil war, such exceptions are utilized to give a sense of

cultural continuity to the funerary practices reserved to the LTTE�s

fighters. An analysis of the exceptions to cremation within Hinduism is

obviously beyond the aim of this paper. Therefore I will restrict myself

to mentioning that these exceptions are associated with either economic

reasons (poor people do not have the resources to cremate their dead) or

religious ones. From a religious perspective, the concept of the

cremation ritual as a sacrifice offered to the gods has in fact several

implications: in case of �bad death�, that is non-voluntary and untimely

death (for instance, death by drowning, act of violence or some kinds of

disease), the body does not symbolize an appropriate sacrifice to the

gods, and is therefore not cremated8.

However, there are other cases in which the corpse is

not cremated: this happens when the dead is a child or an ascetic. With

regard to children, there are cross-cultural evidences of different

practices performed for those who die in the early years of their life.

The reason for the specific treatment of dead children�s bodies within

Hinduism has given rise to a widespread debate (see Das 1976 and

Malamoud 1982). Scholars have suggested several interpretations, some of

them stressing on the characteristic of liminality showed by children.

With regard to ascetics, they can also be regarded as

liminal figures, because of their transcending the customary partitions

of Hindu society and being located in the symbolic limen between life

and death. The burial of ascetics is in fact justified on the basis of

their renunciation of ordinary life. As Charles Malamoud points out, La

c�r�monie complexe qui marque l�entr�e en �renoncement� consiste �

laisser s��teindre les feux sacrificiels apr�s y avoir fait br�ler,

ultime oblation, ultime combustible, les divers ustensiles du sacrifice.

Les feux ne sont pas abolis pour autant : ils sont int�rioris�s,

inhal�s, on les fait �remonter� en soi [�]. cuit de l�int�rieur, et de

son vivant m�me, le samnyasin n�a pas a �tre cuit apr�s sa morte : il

n�est donc pas incin�r�, mais inhum� [�]. en int�riorisant leurs feux,

ils ont aussi aboli la possibilit� d��tre transport�s vers une divinit�

qui leur soit ext�rieure. En s�instituant d�embl�e comme offrande, et en

persistant jusqu�au bout dans ce r�le, ils ont fait de leur propre

personne, de leur atman identifi� au Soi universel, leur divinit� (1989:

65).

Thanks to the exception represented by the interment of

ascetics, Tamil civilians have the opportunity to place the burial

practice within the mainstream of Hindu tradition. In order to provide

an understanding of the symbolic analogy between ascetics� interment and

the Maaveerar�s burial we have to dwell upon the self-representation of

the LTTE fighters. The combatants are portrayed as men and women who are

not involved in the �bad habits� of ordinary people: they do not drink,

do not smoke and do not have forbidden sexual intercourses. Abstaining

from alcohol and cigarettes is significant particularly for male

fighters, because in Tamil culture women are not supposed to drink or

smoke. With regard to female fighters the most important peculiarity is

therefore their purity:

The LTTE ideal of the armed guerrilla woman puts forward

an image of purity and virginity [�]. The women are described as pure,

virtuous. Their chastity, their unity of purpose and their sacrifice of

social life supposedly give them strength. The armed virginal woman

cadre ensures that this notion of purity, based on denial, is a part of

the social construction of what it means to be a woman according to the

world view of the LTTE (Coomaraswamy quoted in Schrijvers 1999: 316).

Michael Roberts suggests that the ascetic mould of the

LTTE fighters implies �the influence of Hindu tradition of tapas

(strength via abstinence) as well as Maoist strains of revolutionary

selfdiscipline� (1996: 256). The ascetic attitude of fighters is also a

subject of LTTE-filmography. In this regard Peter Schalk, explaining the

plot of a film on the Black Tigers � the suicidal commandos �, points

out:

The hero of the film is described as a tavan, �ascetic�,

not by the word, but by his behaviour. Although he is of marriageable

age, there is no sign of a girlfriend [�]. Living in the group of Black

Tigers, he seems to be dedicated to the holy aim [to free Tamil Eelam]

only (1997: 160).

The symbolic association between fighters and ascetics

is not restricted to their behaviour in life. After their death, the

combatants, as the ascetics, are worshipped and regarded as gods. When I

asked if Tuillum Illam were cemeteries, all the people replied saying

�How can you say such a thing? Tuillam Illam are temples, gods are

seeded [buried] there�. If we take into consideration the expected

behaviour of the Tuillum Illam�s visitors, actually we can realize that

the prescribed practices when going to or coming back from Tuillum Illam

are exactly the reverse of those contemplated in case of visiting

cemeteries. The absence of women and the need to take a bath when coming

back from burial grounds can be considered as the central differences.

The identification of Maaveerar with gods � which would

require a deeper analysis � is not rejected by the LTTE, in spite of

their secular nature. During my fieldwork, I observed that not only

civilians, but also some people involved in the movement, although not

fighters, assert that theMaaveerar are gods and Tuillum Illam are

temples. In my understanding the LTTE do not reject this interpretation

because it is necessary in order to make acceptable the introduction of

the new funerary rituals. In fact, as pointed out by Paul Connerton, in

his book How Societies Remember, All beginnings contain an element of

recollection. This is particularly so when a social group makes a

concerted effort to begin with a wholly new start. There is a measure of

complete arbitrariness in the very nature of any such attempted

beginning. [�] But the absolutely new is inconceivable. It is not just

that it is very difficult to begin with a wholly new start, that too

many old loyalties and habits inhibit the substitution of a novel

enterprise for an old and established one (1989: 6).

It is not surprising, then, to find out that Prabhakaran

himself compares the fallen Tigers to ascetics:

Prabhakaran, the leader of the LTTE, requests the

people to venerate those who die in the battle for Eelam as

sannyasis (ascetics) who renounced their personal desires and

transcended their egoistic existence for a common cause of higher

virtue (Chandrakanthan 2000: 164).

I would argue that the attitude of the LTTE with regard

to the identification of the Maaveerar with gods emerges as an ambiguous

but necessary one. On one side the Tuillum Illam are the places where

the secular values of the future nation are displayed: the ideological

rejection of all the differences among people (caste, class and gender

differences) is symbolically carried out through the performing of the

same funerary rituals and the building of equal tombs. On the other

side, the idea that Tuillum Illam are temples where the Maaveerar/gods

are worshipped allows the LTTE to avoid a break with the religious

feelings of civilians, guaranteeing popular consent to the new project

of nation-building.

Notes

1 Tamil Eelam refers

to the separate state claimed by LTTE (Liberation Tigers of Tamil

Eelam).

2 Christians sometimes are buried

close to the area where Hindus perform cremation.

3 Personal interview, 7 December 2002.

4 In passing we may observe that

Prabhakaran is supposed to take all central decisions regarding the

fighters. The LTTE�s members themselves explained to me that, although

many decisions are joint resolutions, actually is better to ascribe them

to the leader. In this way people will accept them more easily.

5 Although the detailed description of

all the interpretations is beyond the aim of this paper, it is necessary

to mention that to some fighters (but not to civilian) the burial of

dead fighters is considered as a return to the practices of the ancient

Tamils, who in fact buried their fallen warriors. References to the

custom of the Chankam period are quoted also in some of the LTTE�s

publications. As Fuglerud points out, �The ideological project of the

LTTE is directed towards homologising the pre- and post-colonial

situation, of linking the present claim for statehood with the

restoration of authentic Tamil culture� (2001: 203). For further

details, see also Cheran 2001, Natali 2004.

6Here has to be reminded that the

destruction of Tuillum Illam is not officially acknowledged either by

Sri Lankan government or by international organizations such as

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC).

7 For further details on the

ceremonies outside Sri Lanka, see Cheran (2001) for the Canadian case,

and Natali (2002) for the Italian case.

8 This does not necessarily mean that

the body is buried: sometimes it is indeed set adrift on a river

(children too are often treated in this way).

References

Bloch, M. e Parry, J. (eds.)

1982 Death and the Regeneration of Life, Cambridge, Cambridge University

Press.

Chandrakanthan, A.J.V.

2000 �Eelam Tamil Nationalism. An Inside View�, in J.A. Wilson, Sri

Lankan Tamil Nationalism. Its Origins and Development in the 19th and

20th Centuries, London, Hurst: 157-175.

Cheran, R.

2001 �The Sixth Genre: Memory, History and the Tamil Diaspora

Imagination�, Colombo, Marga Monograph Series on Ethnic Reconciliation,

VII.

Connerton, P.

1989 How Societies Remember, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Das, V.

1976 �The Uses of Liminality: Society and Cosmos in Hinduism�,

Contributions to Indian Sociology, X, 2: 245-263.

Fuglerud, �.

1999 Life

on the Outside. The Tamil Diaspora and Long Distance Nationalism,

London, Pluto Press.

Knipe, D.M.

1977 �Sapindiikarana: The Hindu Rite of Entry into Heaven�, in F.E.

Reynolds e E.H. Waugh (eds.), Religious Encounters with Death,

University Park and London, Pennsylvania State University Press: 111-

124.

Malamoud, Ch.

1989 Cuire le monde. Rite et pens�e dans l�Inde ancienne, Paris, La

D�couverte.

Mosse, G.L.

1990 Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, New York,

Oxford University Press.

Natali, C.

2002 �Uno spazio scenico per la memoria: la commemorazione dei caduti

tamil attraverso la danza�, in A. Destro (ed.), Antropologia dello

spazio. Luoghi e riti dei vivi e dei morti, Bologna, Patron: 77-111.

2004 Sabbia sugli d�i. Pratiche commemorative tra le Tigri tamil (Sri

Lanka), Torino, il Segnalibro.

Roberts, M.

1996 �Filial Devotion in Tamil Culture and the Tiger Cult of Martyrdom�,

Contributions to Indian Sociology, 30, 2: 245-272.

Schalk, P.

1997 � The

Revival of Martyr Cults among Ilavar �, Temenos, 33: 151-190.

Schrijvers, J.

1999 �Fighters, Victims and Survivors: Constructions of Ethnicity,

Gender and Refugeeness among Tamils in Sri Lanka�, Journal of Refugees

Studies, XII, 3.

Swami, N.

2002 Tigers of

Lanka. From Boys to Guerrillas, Colombo, Vijitha Yapa.

Tonkin, E.

1992 Narrating Our Pasts. The Social Construction of Oral History,

Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.