|

NATIONS & NATIONALISM

A Letter to Dr.Hellpach,

Minister of State

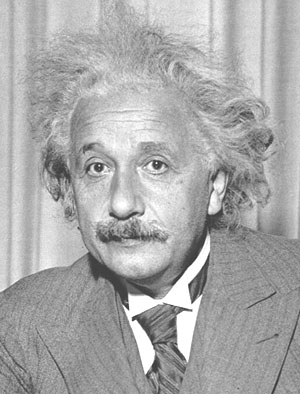

Albert Einstein

Written in response to an article by Professor Hellpach ,

which

appeared in the Vossische Zeitung in 1929.

Published in Mein Weltbild, Amsterdam: Querido Verlag, 1934.

"...The Jews are a community bound together by ties of

blood and tradition, and not of religion only: the attitude of the rest

of the world toward them is sufficient proof of this. When I , came to

Germany fifteen years ago I discovered for the first time that I was a

Jew, and I owe this discovery more to Gentiles than Jews... ..a communal purpose without which

we can neither live nor die in this

hostile world can always be called by that ugly word (nationalism). In any case it is a

nationalism whose aim is not power but

dignity and health. If we did not

have to live among intolerant,

narrow-minded, and violent people, I should be the first to throw

over all nationalism in favor of universal humanity. The objection that we

Jews cannot be proper citizens of the German state, for example, if we want

to be a 'nation' is based on a misunderstanding of the

nature of the state

which springs from the intolerance of national majorities.

Against that intolerance we shall never be safe, whether we call

ourselves a people (or nation) or not..." "...The Jews are a community bound together by ties of

blood and tradition, and not of religion only: the attitude of the rest

of the world toward them is sufficient proof of this. When I , came to

Germany fifteen years ago I discovered for the first time that I was a

Jew, and I owe this discovery more to Gentiles than Jews... ..a communal purpose without which

we can neither live nor die in this

hostile world can always be called by that ugly word (nationalism). In any case it is a

nationalism whose aim is not power but

dignity and health. If we did not

have to live among intolerant,

narrow-minded, and violent people, I should be the first to throw

over all nationalism in favor of universal humanity. The objection that we

Jews cannot be proper citizens of the German state, for example, if we want

to be a 'nation' is based on a misunderstanding of the

nature of the state

which springs from the intolerance of national majorities.

Against that intolerance we shall never be safe, whether we call

ourselves a people (or nation) or not..."

Dear Dr.Mr.Hellpach,

I have read your article on Zionism and the Zurich Congress and feel, as a

strong devotee of the Zionist idea, that I must answer you, even if only

shortly.

The Jews are a community bound together by ties of blood and tradition, and

not of religion only: the attitude of the rest of the world toward them is

sufficient proof of this. When I , came to Germany fifteen years ago I

discovered for the first time that I was a Jew, and I owe this discovery

more to Gentiles than Jews.

The tragedy of the Jews is that they are people of a definite historical

type, who lack the support of a community to keep them together. The result

is a want of solid foundations in the individual which amounts in its

extremer forms to moral instability. I realized that salvation was only

possible for the race if every Jew in the world should become attached to a

living society to which he as an individual might rejoice to belong and

which might enable him to bear the hatred and the humiliations that he has

to put up with from the rest of the world.

I saw worthy Jews basely caricatured, and the sight made my heart bleed. I

saw how schools, comic papers, and innumerable other forces of the Gentile

majority undermined the confidence even of the best of my fellow-Jews, and

felt that this could not be allowed to continue.

Then I realized that only a common enterprise dear to the heart of Jews all

over the world could restore this people to health. It was a

great

achievement of Herzl's to have realized and proclaimed at the top of his

voice that, the traditional attitude of the Jews being what it was, the

establishment of a national home or, more accurately, a center in Palestine,

was a suitable object on which to concentrate our efforts.

All this you call nationalism, and there is something in the

accusation. But a communal purpose without which we can neither live nor

die in this hostile world can always be called by that ugly name. In any

case it is a nationalism whose aim is not power but dignity and health.

If we did not have to live among intolerant, narrow-minded, and violent

people, I should be the first to throw over all nationalism in

favor of universal humanity.

The objection that we Jews cannot be proper citizens of the German

state, for example, if we want to be a "nation," is based on a

misunderstanding of the nature of the state which springs from the

intolerance of national majorities. Against that intolerance we shall

never be safe, whether we call ourselves a people (or nation) or not.

I have put all this with brutal frankness for the sake of brevity, but I

know from your writings that you are a man who stands to the sense, not the

form.

|