[see also

One Hundred Tamils of 20th Century - S.Sivanayagam]

Book Note

by

Sachi Sri Kantha

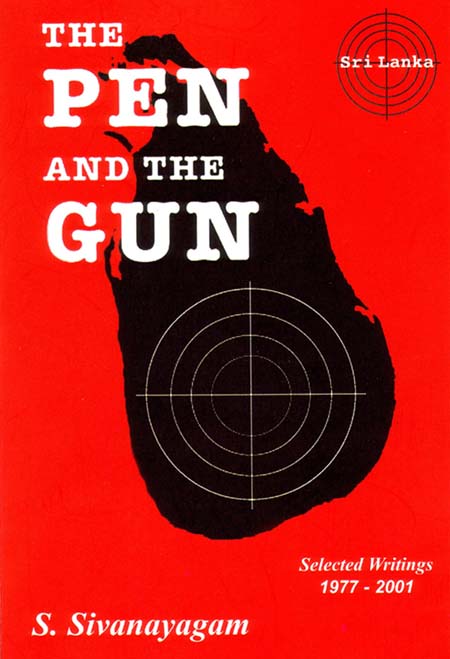

- This book mainly consists of 80 editorials the author had penned

between 1977 and 2000, for four journals; Saturday Review, Tamil Information

Magazine, Tamil Nation and Hot Spring. It also includes a few tracts

and elegies. Of the tracts, Sivanayagam�s �Open

Letter to the American Ambassador in Sri Lanka�, dated March 11, 2001,

is a memorable one. Though it was addressed to Mr.Ashley Wills, the

then American ambassador in Colombo, its text seems timeless in its

appeal. Among the elegies, those describing the activities and services of

educator Handy Perinbanayagam,

Senator S.Nadesan, attorney

K.Kanthasamy,

journalist

Rita Sebastian,

Professor

Alfred Jeyaratnam

Wilson and

Professor Christie Jeyaratnam Eliezer are meritorious.

Foreword by

Brian Senewiratne, 2001

It is an honour for me, a Sinhalese, to be invited to write a Foreword to

a book on the problems facing the Tamil people in Sri Lanka. I hope that my

doing so is not a kiss of death to the book! Siva appreciated this risk but

wrote to me with characteristic defiance, "Damn those who refuse to go

through the book because Brian's name appears on it. Posterity is on our

side, Brian." I hope for posterity's sake that the Sinhalese will go through

this book and not do what President Jayawardene did to the Saturday Review,

i.e. to close it because he could not face the truth.

The Tamils have been systematically discriminated against by a succession

of Sinhalese-dominated governments for more than fifty years. In the past

two decades these oppressed people have been trying to establish (or rather,

re-establish) a separate independent Tamil nation in the pursuit of the

right of self-determination. There are those who think that the only way to

reach this goal is through the barrel of a gun and have armed themselves

with AK47s. There are others whose "gun" is their pen, which, if properly

used, is probably more effective than the conventional gun. The old adage

"the pen is mightier than the sword (gun) is, and has always been, true.

Siva is an expert with the pen and has used this God-given gift with

courage, determination and at tremendous cost to himself and his family for

nearly two decades. His reward has been persecution, illegal arrest and

detention, and even being chained to a hospital bed in India where he sought

refuge from the barbaric regime in Colombo. His life has been reduced to

that of a gypsy. Amazingly, he goes on struggling and writing.

I first "met" Siva in 1982 when I read a remarkable journal coming out of

Jaffna, the Saturday Review, which was edited by him. That was compulsory

reading. With Jaffna brutalised by the armed forces behaving like an army of

occupation, there were two publications coming out of Jaffna, the Saturday

Review, an English weekly, and Suthanthiran , a Tamil bi-weekly, both of

which published information about atrocities in the Tamil area. The Saturday

Review, in English, was the only one through which the problems facing the

Tamil people were transmitted to the Sinhalese people and the outside world.

It had the largest circulation of any Sri Lankan paper outside the country.

Those who have missed the literary gems � the editorials written by Siva -

will find these reproduced in this book. President Jayawardene had no answer

to Siva. His answer was to ban the Saturday Review and attempt to arrest

Siva. Miraculously he escaped � a story in itself.

I followed Siva to the Tamil Nation, Tamil Voice International, which

incidentally published several of my articles, and to Hot Spring. His

outstanding editorials and articles from these journals are found in this

book. He took on the Sinhalese leaders without fear or favour and continues

to do so. He also took on the so-called Sri Lankan diplomats who have been,

and still are "Sinhalese" diplomats. Siva's "assault" on the one-time Sri

Lankan ambassador to the U.S.A is well worth reading. However, from my

perspective. the most fascinating part of the book is the Introduction in

which he deals with the origins of the Sinhala people. Perhaps I should

thank the writers of the Mahavamsa for this arrant nonsense which has done

so much damage to the country. Siva's hilarious, but perfectly correct,

comments on this claptrap is well worth repeated reading.

Those of us who are addicted to writing will appreciate not only the

contents of this book but also the style of presentation. It is ofcourse the

difference between a journalist and a doctor of medicine! When I wrote a

short piece for the flyer for this book, Siva responded by telling me that I

could afford to he critical of any part of the contents. I low can I when I

agree completely with what he has written? No one could have done a better

job.

As I have said I "met" Siva when I got addicted to reading the Saturday

Review in the early eighties. Amazingly, I had not actually met him

physically until June 2001 when I was invited to London to address a

luncheon meeting of the International Foundation of Tamils on "The Abuse of

Democracy in Sri Lanka". One reason for not being able to meet him in all

those years that I have been running round the world campaigning for the

cause of the Tamil people could be either that he was in hiding or in some

terrible jail in India without charge or trial or chained to a hospital bed

in Madras where he sought refuge from oppression in his own homeland. In

July 200 I while waiting to deliver an address on "Democratization. Time for

radical change" at the "Sivan Kovil" hall in London, I thought I might spend

the afternoon with Siva. I visited him in his one-room-shared-kitchen-toilet

accommodation in London. It was perhaps my finest hour. I marvelled at the

sacrifice that he had so ungrudgingly made to the cause of the Tamil people.

I am delighted that he has dedicated this book to one of the finest

people I have met, a dear friend who is no more, Kandiah Kanthasamy. My only

regret is that this book is in English. It should be translated into Sinhala

and made compulsory reading in Sri Lanka. I hope that someone with a sense

of true patriotism will do this.

From the Introduction -

Sri

Lanka's post-independence history could be said to be divided, symbolically,

into two phases � the supremacy of the sword and the ascendancy of the gun!

The dividing line between the two falls roughly around the mid-eighties. The

sword is the one you see in Sri Lanka's national flag and in the official

emblem: a figurative but yet ferocious-looking lion holding a threatening

sword in its right paw, with its tail raised in the air � altogether a

picture of aggression.

Sri

Lanka's post-independence history could be said to be divided, symbolically,

into two phases � the supremacy of the sword and the ascendancy of the gun!

The dividing line between the two falls roughly around the mid-eighties. The

sword is the one you see in Sri Lanka's national flag and in the official

emblem: a figurative but yet ferocious-looking lion holding a threatening

sword in its right paw, with its tail raised in the air � altogether a

picture of aggression.In life, we take many things for granted, and not

many people, certainly not the non-Sri Lankans, are likely to pause and

wonder how the lion came to be in Sri Lanka's national flag, nor why some

patriotic Sinhalese like to call themselves members of the Lion Race.

To understand this mindset, one has to go back to a pseudo-historical

work called the Mahavamsa ("The Great Chronicle') written by Buddhist

bhikkhus, which as a leading Sinhalese historian K.M.de Silva says, was

"permeated by a strong religious bias, and encrusted with miracle and

invention".' Compiled at the beginning of the sixth century after Christ,

but containing as it does the island's recorded history from 500 B.C. it is

also embellished with tales of mythical beings and miracles.

While it is possible to separate the grain from the chaff and use it as

an invaluable source of the rich historical tradition of the island, the

myths and legends that adorn the Mahavamsa unfortunately took a permanent

grip on the popular Sinhalese imagination; with disastrous results to the

country and its peoples.

The inventive narration of the founding of Sri Lanka with the arrival of

the Sinhalese is a case in point. The story surrounding Vijaya, the supposed

founder of the Sinhalese race, as is given in the Mahavamsa is not only

fanciful but sordid as well. The Sinhalese people, it is said, are

descendants of an "amorous" princess in the country of the Vangas (Bengal in

India) who mated with a lion! The soothsayers had "prophesied her union with

the king of beasts", says the chronicle, "and for shame the king and queen

could not suffer her:" So she left her home, seeking an independent life and

joined a caravan. What follows is an intriguing account that has all the

drama that would make a good Hollywood blockbuster!

The caravan was travelling to the "Magadha country" and on the way a lion

attacked it in the forest. While "the other folk fled this way and that" the

princess fled along the way by which the lion had come. "When the lion had

taken his prey and was leaving the spot he beheld her from afar, love (for

her) laid hold on him, and he came towards her with waving tail and ears

laid back. Seeing him she bethought her of that prophecy of the soothsayer

which she had heard, and without fear she caressed him stroking his limbs.

The lion, roused to fiercest passion by her touch, took her upon his back

and bore her with all speed to his cave, and there he united with her, and

from this union with him the princess in time bore twin-children, a son and

a daughter " The son's hands and feet were formed like a lion's and the

mother named him Si(n)habahu. The daughter was named Si(n)hasivali. Thus

they lived in the lion's cave for sixteen years.

Now, it was the lion's habit to close the cave entrance with a rock

before setting forth in search of prey. When Sihabahu was sixteen, he asked

his mother: "Wherefore are you and our father so different, dear mother?" So

she told him. The next thing that happened was of course what could he

called in contemporary terms, a case of malicious desertion! When the lion

had gone out in search of prey, young Sihabahu dislodged the rock that

covered the cave, carried his mother and sister on his two shoulders,

clothed themselves with branches of trees and escaped to the border village.

When the lion returned and found the wife and children gone, "he was

sorrowful, and grieving after this on, he neither ate nor drank", says the

Mahavamsa. l le set in search of them in neighbouring villages, and wherever

he went, the people fled in fear. They then went to the king and told him: "

The lion ravages the country. ward (this danger) O' King."

The king offered a reward of a thousand gold pieces to anyone who would

bring the lion's head. Since there were no takers, he increased the reward

in turn to two thousand and then three thousand gold pieces. Sihabahu

accepted the promise of reward and despite his mother restraining him went

to his lather's cave. As soon as the lion saw his son, he came forward with

love towards him. Sihabahu's arrow struck the lion's forehead, but because

of his tenderness towards his son, the arrow rebounded and fell on the earth

at the youth's feet. And so it fell three times, but "then did the king of

beasts grow wrathful and the arrow sent at him struck him and pierced his

body."

Sihabahu took the head of the lion with the mane and returned to the city

to receive a hero's welcome. In course of time, he founded the new "kingdom

of Lala", made Sihasivali (his sister) the queen, and by her had "twin sons

sixteen times", thirty two sons in all. The eldest of them was named Vijaya

whom the king consecrated as prince-regent. Vijaya, according to the

Mahavamsa, turned out to be ''of evil conduct". He, and his followers, seven

hundred of them, perpetrated "many intolerable deeds of violence" that

angered the people. The father Sihabahu lost his patience, half-shaved the

heads of the lot of them and put them on a ship banishing them from his

kingdom. It was this Vijaya who eventually landed in Lanka and founded the

Sinhala race, according to the chronicle!

Not a pleasant way to trace the origin of the Sinhalese people � a story

of animal descent, an over-sexed princess, a parricide father, an incestuous

marriage and a wicked son banished by his people! One would have expected

the Sinhalese people to have dismissed this story of a shameful genealogy

from their minds, and laughed it off � given their habitual sense of humour

� (unlike the Tamils, they have a greater capacity to laugh at themselves)

as arrant nonsense. But alas, their politicians were of a different mould.

When the leaders of predominantly Hindu India opted for the Asoka Chakra,

with its Buddhist connotation of Peace as the national emblem at the time of

independence, the Buddhist leaders of Sri Lanka who claim that the island is

the first and final repository of Buddhism, Ahimsa and Maithreyedecided to

make a ferocious-looking lion holding a sword on its paw as their flag and

emblem!

This represented an unfortunate state of mind, which was bound to have a

deleterious effect on the future history and governance of the country.

Should it surprise anyone that the country has been experiencing one form of

violence or another and shedding of blood for 45 years of its 53-year

post-colonial history?.

The history of violence in the country wears several faces: Sinhala mob

violence against Tamils (1956 1958); Sinhala dissentient violence against

the State (1971); Sinhala State violence against Sinhala dissent (1971);

Sinhala State violence against Tamil civilians (1977, 1981, 1983. Tamil

militant violence against the State (1983 ...); Tamil militant violence

against Tamil dissent...Tamil militant violence against Sinhalese

civilians.... and suddenly in mid - 1987 Sinhala violence turned inwards

with floating corpses in rivers and streams in the south, while in the North

and East, an "Indian Peace-Keeping Force" went to war with the Tamil Tigers.

By now the violence had peaked into a frontal war between two

nationalisms that has shown no signs of abating after seventeen years of

bloodshed and loss of seventy thousand human lives. Bad enough for the

Sinhala State to carry a historical baggage going back to 2500 years,

complete with lion and sword, but worse for the Sinhalese people to burden

themselves with myths and legends that reflect badly on their own past.

Historically speaking, one could say the tiger- an equally ferocious

predator in the jungle as the lion -was at least a late starter in the

jungle politics of Sri Lanka! The calculation must have been that against

the Sinhala Lion and the Sword of State, the effective counterpoise would be

a Tamil Tiger and an AK 47 gun!

America, when it started out, was a blank page of history waiting to be

written upon", wrote Tocqueville, the French political scientist. The

problem about Sri Lanka is that it is a country heaving with a heavy cargo

of the past that even to identify a national hero, the Sinhalese go back two

thousand years, before Christ, to remember a Dutugemunu! (The Tamils at

least can claim a living one!) What they choose to remember and what they

recall with pride are matters for Sinhalese politicians and the Sinhalese

people, but by foisting what they believed was a symbol of Sinhala pride

(and four Bo-leaves in the flag to denote Buddhist hegemony) in a country

that was multi-ethnic, multi-cultural, multi-lingual and multi-religious,

they had legitimised Sinhala-Buddhist majoritarianism at the very beginning

of life as an independent nation. Two stripes of red and green placed

alongside the Lion flag - like the two stripes on a squirrel, - as

Tamil Senator S.R.Kanaganayagam quipped at that time, were added later as a

patronizing gesture towards the presence of two "minorities" in the country

, the Tamils and the Muslims. As for the fair-skinned Burghers, they were

not even given a thought. They were expected to leave the country, which

they did, in large numbers � for Australia. The Tamil exodus out of the

country was to start 35 years later, with the State-inspired pogrom of 1983.

That year remains as a major watershed.

The title of this book needs a word of explanation. The contents here

correspond almost nearly (beginning 1982) with the period when the gun

had come into play in the political life of the country (Sri Lanka).

Previously, I had spent thirty years in Colombo, involved with the written

word - in newspaper journalism, advertising, tourist promotion, magazine

publishing but the kind of writing devoid of political content. The events

in Jaffna in May-June 1981 were to rouse the political animal in me. If

any State could virtually declare war against its own citizens, and in a

part of its own territory (Jaffna) and do it unashamedly....

that happened in

1981 . Nancy Murray, a member of the Campaign against Racism and

Fascism, and of the Council of the Institute of Race Relations said in a

subsequent report:

"By 1981, the Liberation Tigers had killed perhaps twenty

policemen, many of them notorious torturers. In April and May of

1981, following the

Neervely bank robbery, twenty seven men were arrested, and at

least twenty two of them, according to an Amnestv International report,

tortured in a number of ways and then chained to walls at the Elephant

Pass army camp and elsewhere for six months at a time. Against the

background of' relentless State repression, Jayawardene's effort to

defuse the situation by calling elections for District Development

Councils was probably doomed, from the start, even if he had not aroused

Tamil suspicions by sending up a contingent of 300 specially trained

Sinhalese policemen to oversee the election proceedings in Jaffna.

"The run-up to the elections was predictably violent. Tamil Youth groups

denounced the TULF, for going along with the elections - they viewed the

DDCs as toothless and TULF cooperation as a sell-out. On 24 May, a UNP

candidate was assassinated and the army went on a rampage of looting and

torture. And then, on 31 May, an unidentified gunman fired some shots at

an election meeting, and the tense atmosphere exploded into

State-sponsored mayhem. With several high-ranking Sinhalese security

officers and two Cabinet Ministers, Cyril Mathew and Gamini Dissanayake

(both self confessed Sinhala supremacists), both present in the town,

uniformed security men and plainclothes thugs carried out .some well-

organised acts of destruction. They burned to the ground certain chosen

targets -

including the

Jaffna Public Library, with its 95,000 volumes and priceless

manuscripts, a Hindu temple, the office and machinery of the independent

Tamil newspaper Eelanadu, the house of the MP for Jaffna, the

Headquarters of the TULF, and more than 100 shops and markets. Four

people were killed outright. No mention of this appeared in the national

newspapers, not even the burning of the Library, the symbol of the

Tamils' cultural identity....'

As a Tamil, as a book-lover, what happened was saddening and shocking

enough. But as a newspaperman by training, the way the Colombo newspapers

blacked out - what should have been banner headlines on Page 1 - outraged my

sensibility as a journalist. As a believer in the notion that an unseen hand

shapes our lives, confirmation of it came when I received an urgent message

from

K.Kanthasamy (to whom this book is dedicated) asking whether I could

meet with few Tamil activists at a meeting he would be arranging. It

was out of this meeting came the action plan for an English-language

newspaper for the Tamils, to be brought out from Tamil soil, and with me to

accept both the responsibility (and the risk) of editing such a paper. Used

to quick decisions, foolish or otherwise, I did not hesitate. In

September, I gave the required three months' notice of resignation at the

Colombo Plan Bureau, shifted myself and my family to Jaffna and in January

1982, launched the Saturday Review. And with that my own future was sealed.

Having lived a life with neither glory nor ignominy for the first fifty

years of my life, the next twenty was to become a roller-coaster ride!

Hounded by the Sri Lankan government, escape to India by a midnight

country boat, separation from the family, jailed by the Indian

government without charge for one year, incarceration in two jails,

Vellore and Madras, chained to the bed in the Madras General Hospital, a

further detention under police guard for six months, litigation after

litigation paid for by friends of the Tamil Forum Ltd., in the UK, a nomadic

life for one and a half years through six to seven countries and finally

hard earned safety in the West. There are no regrets however. Journalism is

no journalism if it lacks passion. But it goes with a price. Having paid

that price, I believe this book is its own reward."

Two tales of a city named Jaffna & Sivanayagam's Pen and the Gun

by Ajith Samaranayake, Sri Lanka Sunday Observer, 17 March 2002

The Norwegians are coming, the Prime Minister goes to Jaffna and hopes rise

again about the end to our communal blood-letting. The peace forces are on

the march, the doves take to the skies and the hawks uncertainly scan the

horizon.

In the corridors of the mass media the men and women come and go not talking

like T.S. Eliot's women about Michael Angelo, but about Anton Balasingham

who in an earlier incarnation as A.B. Stanislaus had been such a quiet young

man when he was at the 'Virakesari' and the British High Commission.

Veteran observers, seasoned cynics and men about town, however, can be

pardoned for feeling a sense of deja vu. Haven't we seen all this before

stretching from Thimpu to Jaffna via Madras and New Delhi? What is the

assurance that this time round the truce will hold and things will not come

apart as it has happened so many times in the past?

To understand this dilemma and predicament S. Sivanayagam's 'The Pen and the

Gun' offers us an invaluable key. Sivanayagam, who edited the 'Saturday

Review' in Jaffna from January 1982 to July 1983 when it was banned, has

since been the editor of various publications in India and Britain and has

led a nomadic life in exile in India, Singapore, Honk Kong and several

African countries before obtaining political asylum in France and later

Britain not to mention one and a half years he spent in a jail and under

Police guard in a hospital in Madras at Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi's

pleasure when the latter was desperately trying to keep the Indo-Lanka

agreement in place.

Sub-titled 'Selected Writings 1977-2001' this anthology offers what is

surely a unique insight into the evolution of the one intractable issue

which has plagued Sri Lanka from Independence but which for several decades

after was swept under the carpet as a dirty little secret which nobody dared

to utter in polite company.

This book is more than an anthology of collected writings. Although not an

autobiography it offers insights into the writer who on his own admission

had led a fairly tranquil life in journalism, advertising, the Ceylon

Tourist Board and finally the Colombo Plan until he was propelled by a sense

of mission following the mounting attacks on the Tamil community and its

sense of collective helplessness to assume an interventionist role.

The Saturday Review which Sivanayagam edited from Jaffna was unusual in the

sense that it was a newspaper sprung from the soil of the Tamil heartland

but edited with aplomb in a language which has remained the language of the

ruling class in Sri Lanka and the lingua franca of the elite irrespective of

the homage which is ritually paid to the official language which appears

increasingly to be only for the hoi polloi.

In another sense 'The Pen and the Gun' is the biography of a whole people.

There is a sense of elegy in Sivanayagam's description of the Jaffna of days

gone by when in the famous words of the late Maoist leader N. Sanmugathasan

the North was regulated by a 'postal order economy'.

The boys were studious, the people law-abiding and their ultimate trophy was

a good Government job. Sivanayagam says that the used to joke in Jaffna that

even if you looked after hens it should be for a Government department for

there was a respectable salary and pension attached to it! Another joke had

it that if you tripped and fell in Jaffna the chances were that you would

fall on a school teacher or a pundit!

How then did such a tranquil people take to arms, how did the haven of peace

erupt in flames. How did Jaffna spawn one of the most violent movements of

terror and how was it able to bring about the near prostration of a country?

It is the familiar tale but Sivanayagam tells it in a way which is all his

own. He has a superb command of the English language and when necessary he

can slip into the vernacular as well. In that sense he is the English

parallel to B.A. Siriwardena, the unbeatable editor of the 'Aththa' whose

loss is widely felt.

Sivanayagam recalls

S. Nadesan who appeared for the 'Saturday Review' in the Supreme Court

telling him that some of the politically-appointed judges of the time were

squirming when he quoted from the editorials 'Because your language can

sometimes be very biting'.

So much for the singer but what of the song? As we have already observed it

is the familiar one but one which we will be ignoring at our peril if we are

to remain as one nation and one people. The Tamils implicitly trusted the

Sinhala leadership at Independence to the extent that two of them, C.

Suntharalingam and G.G. Ponnambalam, became Ministers of the first Cabinet.

But soon the marginalisation of the Tamil community started under all

Governments, both UNP and SLFP, and when the Federal Party took to the

Gandhian path they were rebuffed with violence. 1958 could have been

dismissed as an aberration if it was not followed regularly until the Tamil

people felt estranged to the point of demanding separation.

The book consists basically of the editorials Sivanayagam had written but a

solid ideological underpinning is provided by a series of articles tracing

Sinhala-Tamil relations, both historically and otherwise, under the title of

the 'Inevitability of Tamil Eelam'. Sivanayagam has often been demonised as

the supreme Eelam propagandist but that is to make him a cheap demagogue. He

is a greater man and a man of wide humanistic sympathies.

Yet I have one lingering doubt. Sivanayagam comes close to idolising

Velupillai Prabhakaran and after the tortures the Tamil community has been

subject to who can quarrel with him? But given the fact that Prabhakaran is

the supremo of the LTTE will he be amenable to a solution which while being

honourable by the Tamil people can still be offered to the large Sinhala

constituency as an acceptable proposition? After all it was Sivanayagam

himself who has described Tamil Eelam as a 'state of mind' something like

Pirandello's 'Six Characters in Search of an Author'.

Whether Eelam will be transformed from a state of mind to a nation state or

whether Sri Lanka as we know it will hold surely depends on the historic

sense and sagacity of all our leadership transcending both communal and

political boundaries.