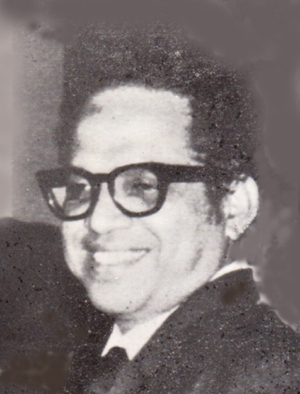

K.Kanthasamy was abducted in

June 1988 by a Tamil 'group' and was presumed killed.

He was a human rights activist who organised

practical assistance for Tamils displaced and

dispossessed by the conflict in the island. He also

helped to found the Tamil Information Centre in

London. He returned to Jaffna in 1987 after the

signing of the Indo Sri Lanka Accord and was engaged

in refugee rehabilitation work in the Tamil homeland

at the time of his abduction.

"...As a Tamil, I

must confess to a feeling of shame not unmixed with

anger, that a so called Tamil 'liberation' group

should have been responsible for Kantha's abduction

and murder. We, as a people, cannot liberate

ourselves from anything by killing those with whom we

disagree. Kantha was an honourable man. He was a good

man. And to him, work was worship - he was the karma

yogi par excellence. And when we honour his memory

and his work, we not only strengthen that which is

good and honourable amongst the Tamil people - we

also renew our own commitment to the Tamil national

liberation struggle to which Kantha gave his

life."

It was more than twenty

five years ago, in the early 1960s, that I first met

with Kanthasamy. At that time, he was a young lawyer

working in Advocate N. Nadarasa's chambers at

Kollupitiya. But he was already displaying some of the

qualities which would stand him in good stead in the

years to come.

It was more than twenty

five years ago, in the early 1960s, that I first met

with Kanthasamy. At that time, he was a young lawyer

working in Advocate N. Nadarasa's chambers at

Kollupitiya. But he was already displaying some of the

qualities which would stand him in good stead in the

years to come.

He addressed himself, in a systematic and

disciplined manner, to whatever task that was assigned

to him. He was dependable. He was a doer - not a

talker. His honesty and integrity were never in

dispute. And there was an attractive simplicity about

him as he travelled around in a motor scooter from

chambers to Hultsdorf and back. But then, Kantha was a

simple and honest man.

Many years later, I remember meeting him at

Saraswathy Hall in Bambalapitiya. It was a couple of

months after the burning of the Jaffna

Public Library in June 1981. That was an incident

which had left its mark on

the consciousness of many thousands of Tamils,

including myself. Kantha was at Saraswathy Hall,

involved in the campaign to collect books to establish

a new library, writing down carefully the titles of all

the books that were handed over and the names of the

donors. It was a time consuming task and not

particularly glamorous - but, typically, Kantha

approached his duties with cheerfulness and with

dedication.

Kantha had appeared as Counsel before the Sansoni

Commission which inquired into the attacks against the

Tamil people in 1977, and this was the period in

his life that he was working almost full time in the

rehabilitation of Tamils who had been displaced by such

attacks, and who had become refugees in their own

land.

And, it was his involvement in such refugee

rehabilitation work that eventually led him to become a

refugee himself and seek political asylum in the United

Kingdom.

I met with him in London in late 1983 and he took me

with some pride to the newly established office of the

Tamil Information Centre

which he had set up with the help of a few friends. He

was full of the work he was doing, despite a recent

heart attack and despite being told that he would need

to undergo a by pass operation.

There was a certain dignity about all that he did -

he would tell me " You know, when I go to funding

agencies for donations, I tell them that we are not

beggars, but I know that in a way I am begging - but I

beg not for myself but so that we can do something for

our people."

The next few years in London were years of sustained

activity for Kantha. There were occasions when I met

with him, early in the morning, at his home in North

London, before he left for the TIC office which was

situated in South London. He would be dictating letters

to a typist who had come - and, he would leave home,

after the first morning mail was delivered. It was his

way of maximising the efficient use of his time.

And for more than four years, until the signing of

the Indo

Sri Lanka Accord in July 1987, the Tamil

Information Centre and the Central British Refugee

Rehabilitation Fund which Kantha founded served as

important focal points in the Tamil national liberation

struggle.

I remember talking with him for more than 6 hours in

early August 1987, trying to persuade him to change his

decision to close the Tamil Information Centre and go

back to Sri Lanka. As a refugee who had been granted

asylum in the United Kingdom, Kantha could have stayed

in London for as long as he wished but his basic

response was that there was a need for him to go back

and work amongst the Tamil people in the North and East

of Sri Lanka - he felt that refugee rehabilitation work

was the urgent need of the hour and that his own

contribution to the struggle lay in this field.

A couple of days before he finally left the United

Kingdom, Kantha travelled down to Cambridge to spend a

day with my wife and I. We talked for several hours. It

was a time for reminiscences. It was also a time to

look at what the future held for us as a people. Kantha

was not unaware of the difficulties that he would face

from some political groups who may see his work amongst

the Tamil people as a threat to their own influence and

power. But Kantha was not only a simple and honest man

- he was also a courageous one. And as we embraced each

other at my door step, and said good bye, both Kantha

and I were not unaware that we may not see each other

again.

As a Tamil, I must confess to a feeling of shame

not unmixed with anger, that a so called Tamil

'liberation' group should have been responsible for

Kantha's abduction and murder. We, as a people, cannot

liberate ourselves from anything by killing those with

whom we disagree. Kantha was an honourable man. He was

a good man. And to him, work was worship - he was the

karma yogi par excellence. And when we honour his

memory and his work, we not only strengthen that which

is good and honourable amongst the Tamil people - we

also renew our own commitment to the Tamil national

liberation struggle to which Kantha gave his

life.