|

Tamil Eelam - a De

Facto State

Teaching Tamil Tigers : An Eye Witness Account

John S Whitehall, FRACP, Director of Neonatology

Department of Neonatology, Townsville Hospital, Townsville, QLD.

Correspondence:

[email protected]

20 December 2007

For

over two decades, there has been savage conflict in Sri Lanka between a minority

group of Tamils who claim traditional rights for land in the north-east and the

majority, Sinhalese, government in Colombo. The conflict has consumed tens of

thousands of lives, displaced hundreds of thousands, sown agricultural land with

mines, laid waste plantations, and stunted a generation of children. It could be

argued that the only rule of warfare is the respect each side has for the

capacity of the other to terrorise: the desire for self-preservation has tended

to restrict the number of civilians being bombed. Nevertheless, human rights

organisations have reported over 4000 Tamil deaths in recent months. The conduct

and cost of the conflict is obscured by suppression of the press on the

government side and lack of access of the press to the other.

The

Ceasefire Agreement in 2002 between the leaders for Tamil autonomy, the

Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, and the government in Colombo, and the effects

of the Asian tsunami in 2004 have combined to reduce hostilities and permit

greater access to the north-east by foreigners. In this time of relative peace,

I visited the region in January and again in May 2005, delivering antibiotics

and then ventilators and surgical equipment to hospitals throughout the island,

supplied through the generous response of North Queensland to the tsunami.

Driving

north from Colombo to Jaffna, I was struck by the poverty on the Tamil side of

the armed border, the lack of facilities in the hospital in Kilinochchi (the

administrative centre of the �Tamil� land) and the dilapidation of the tertiary

hospital in Jaffna. Only the crowds in the corridors and the patients on the

floors obscured the filth on the walls and passageways. Nothing obscured the

suffering of apparently half-dead people being carried on bare metal stretchers

at perilous angles up and down the stairs, buffeted in the surge. I was struck

by the whites of their fingers as they clung to the metal. Nothing prevented the

recycling of dengue through unscreened windows from sullage that pooled from

broken pipes alongside the wards. One piddling tap leaned vainly against

cross-infection in the crowded children�s barn. Why was this hospital so

different to the many I had visited in the Sinhalese areas? I later learned of

economic sanctions and underfunding by Colombo.

I

volunteered to return to Sri Lanka in September 2005, originally to work as a

paediatrician on the east coast, but diverted by my hosting organisation to work

in Kilinochchi for a couple of weeks and teach �some students who had missed out

because of the war�. I remembered the needs of Kilinochchi and was willing to

comply. About three weeks later, I discovered that my students comprised the

medical wing of the �terrorist� Tigers!

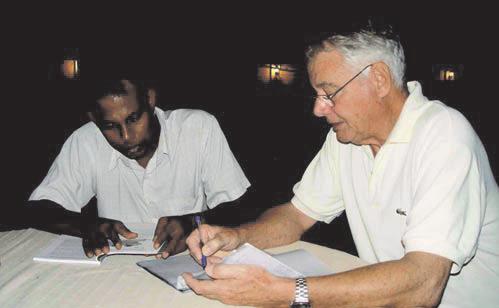

A

home visit by one of the medical students

I met them in a shed whose walls reached halfway to a roof of corrugated iron

that creaked in the heat of the sun, then roared with the monsoon rains as the

weeks extended to three months, and I swapped tales of sick children for tales

of my students� lives.

We

began awkwardly. As I entered, there was a sudden scraping of chairs on the

concrete floor and then a silent standing to attention. I was further surprised

by how many there were � 32 � and their being perhaps a decade older than I had

expected. I introduced myself and asked them to sit. There was more scraping of

chairs. Now they were sitting stiffly and silently. �Does anyone speak English?�

I asked, and began to try to work out what they knew and what they needed. I had

no idea I would grow to love them.

I

realised they needed grounding in the old-fashioned approach of taking a

history, examining methodically, and making provisional diagnoses and plans of

management, though I soon sensed they had had profound experiences in triage and

trauma. They had seen a lot of sick children but were thin on theory, so I

decided to prolong my stay and start at the beginning.

After

about two weeks, we had worked our way to the examination of the respiratory

system and it was then that I discovered how close my students had been to the

acute end of medicine. I invited a man to remove his shirt and a woman to

demonstrate her method of examination and was surprised by the divot out of the

man�s shoulder. Asking him what had happened, I noticed a similar deformity in

the woman�s forearm. Shrapnel and a bullet, they explained, and everyone began

to laugh. �Well, who hasn�t been shot?� I asked, and, to my astonishment, only

about a third raised their hands. �Didn�t you notice our wooden legs?� someone

asked and, adding to my foolishness, three were waggled for my inspection, with

the class now in uproar. Who are these people? I wondered, and began the journey

of discovery.

They

comprised the medical wing of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam and were the

remainder of an original group of over 70 who had been chosen from the ranks of

the infantry because their commanders had concluded they had the potential to

become doctors. The struggle for a Tamil homeland, Tamil Eelam, had entered a

violent phase in the late 1980s, and the problem of casualties had originally

been solved by taking them in small boats to sympathisers in nearby Tamil Nadu,

in India. As the numbers increased and the political situation altered, they

were taken to the hospital in Jaffna. But lives and limbs were lost in

transportation through jungles or around the coast from distant front lines, and

the need for the movement�s own medical wing became obvious.

Paraphrasing

a student's stories of his experiences

In time, I asked them all why they had

joined the Tigers and learned of the deaths and torturing of family members, of

schools bombed, of the bodies of neighbours washing ashore, of mobs rampaging

against Tamils and of discrimination in education and language. Each one had a

saga and each had joined the Tigers because �they spoke less and did more� to

protect their race against what they were all convinced was genocide. They had

all been trained as infantry, but none had forgotten the speech by their leader,

who had asked them to forego fighting for the greater goal of healing their

people.

The

course had started in 1992, with some students needing preparation in maths,

chemistry and English because they had not finished high school. Others had

graduated in biology from university. The course paralleled the curriculum at

Jaffna University but had been interrupted by long periods of service in field

hospitals, in public health campaigns against cholera and malaria, in the

manning of general hospitals, and by the needs of the tsunami, which had wrecked

the north-east coast. The Ceasefire Agreement of 2002 had allowed them to catch

up on formal education, but they were lacking a module on paediatrics, when I

turned up out of the blue. My 32 students were those who had stayed the course.

Others had been unable to resist the call of the armed struggle, some had failed

academically, and five had been killed on active duty.

It

was obvious they needed tuition that emphasised infectious diseases and

malnutrition and it was easy to gather cases for presentation from my rounds in

the ward and from outpatients. The days began with a lecture or two, then moved

to cases, and included examination of the newborn and resuscitation. The poverty

in the nursery was painful � mothers used old handkerchiefs for nappies.

They

had never performed any formal research and were keen to be divided into groups

to review perinatal outcomes, nutrition, causes for acute admission, snake bites

and emotional effects of the tsunami. We found mothers and children to be wasted

and stunted, road accidents to reflect the dangerous driving through the town,

snake bites to be handled well, and counselling to be effective for grief. The

findings were presented on a special research day, which evolved into an

emotional ceremony of graduation.

Student

treating civilian wounded by artillery fire

As the weeks progressed, I

learned more of their lives and could not rest until one began to translate

short stories he had written about their experiences. We began to meet every

night in a small gazebo, sometimes curtained with rain, and went over his

stories, line by line, paraphrasing from Tamil and amplifying for a wider

audience in English. My mind was fascinated by the stories of medicine, my

emotions drawn by their humanity.

I

learned of the development of the medical wing from first aid to reconstructive

surgery, encompassing the triage of mass casualties, blood transfusions on the

front lines, and end-to-end anastomoses of arterial wounds with ketamine

anaesthesia by torch light under artillery fire that thudded shrapnel into the

coconut-trunk walls of their bunker. I learned of organisation and secrecy that

could construct a hospital overnight in preparation for a battle in the morning

. . . and of my students who had worked and worked until the casualties stopped

coming � in their uniforms stiff with blood, on legs that could barely stand and

under the sustained threat of sudden death.

I

could scarcely believe accounts reminiscent of the First World War, and insisted

on interviewing all the students mentioned by name, others not mentioned, and

particular patients, cross-checking the details. I went to battlefields to see

if the layout was as described. It was. Though overgrown by jungle, the bunkers

that had contained the operating theatres were still visible, confirmed by

halfburied vials of empty medical containers. Mounds of dirt confirmed former

protective walls, and abandoned paraphernalia confirmed the fighting. Bones and

shredded uniforms confirmed casualties.

Why

they continued to fight still puzzled me, especially as I visited war cemeteries

and pondered the carnage in which over 17 000 Tamil young people have died in

the past two decades. Understanding began on the afternoon of 27 November, their

equivalent of Anzac Day. My students collected me and, for the first time, I

observed them in uniform, making their way through the cemetery, squatting here

and there with parents of the dead who had begun to arrive in droves to festoon

the graves with garlands and food for their young men and women who �were living

on in the spirit of Tamil Eelam�.

There

were about 3000 graves and soon the cemetery was pulsating with grief. The

burning sun sank beneath a row of palms and I anticipated some kind of communal

eruption of emotion as candles were lit on the graves and flickered on distorted

faces. But there was nothing. No hymns, no chants, no catharsis. Just a speech

on the necessity for more sacrifice. Silently, the crowd shuffled away, leaving

the garlands and the candles to the moonless night. I began to realise what some

people are prepared to endure for freedom.

Students

operating and giving anaesthesia

I had a farewell meal with my students

before I left and before they were dispersed to look after the population of

their Tamil Eelam and the casualties of a war that has escalated. We made

speeches, and they presented me with what was clearly a special gift: a Tiger

flag (which caused anxiety clearing Customs on the way out).

Private

possession of a Tiger flag, I am informed, is not �recklessly supporting a

terrorist organisation�, but detectives from the counterterrorism team of the

Australian Federal Police were keen to explore why I stayed in Kilinochchi when

I learned the identity of the students. I figured teaching doctors how to

resuscitate children was in the interests of the people, whoever controlled

them, but wondered if my career had reached a crossroads!

Subsequently,

I did not mind going over all our overseas phone calls with the police or

explaining why my bank had sent money to England (for a course on radiation

biology), but I was a bit unnerved by the attention I received from immigration

officials when I recently left for New Guinea. Being profoundly Australian, I

found it unsettling to be perceived as being on the �other side�! I hear,

however, that the Department of Public Prosecutions is not proceeding with my

case, which is good news. The bad news is that it is unlikely I will ever be

able to return to Sri Lanka, and the needs of the north-east weigh heavily.

Tamil friends assure me that publicity for the situation is the greatest help I

could offer Sri Lanka. With that in mind, the collection of short stories I

paraphrased will be published in the near future. |