|

S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike Assassination -

Revisited after 50 years

Part 3: Theatrics and Economics

10 October 2009

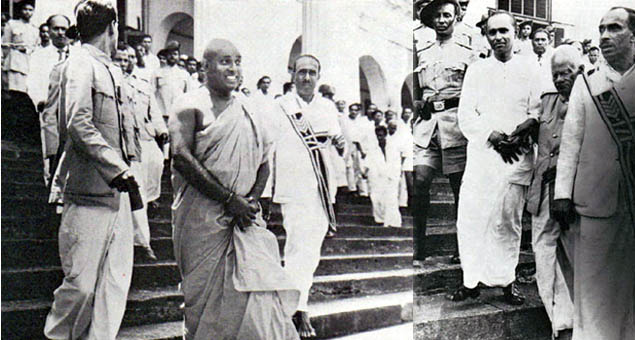

Buddharakita Thera and Somarama Thera leaving the Court house

after their conviction on 10 May 1961

Introduction

It may not be incorrect to state that for some Buddhist monks, a sedate life

style and a saintly persona are anathema for their promotional activities that

deviate from the guidelines set by the Enlightened One, Siddharta Gautama Buddha

(563 BC � 483 BC), aka Shakya Muni. The yellow-tinged robe and shaved head

provide them with easy access to corridors of power to indulge in politicking

and back room deals � in short, theatrics and economics, as I have sub-titled

part 3 of this series.

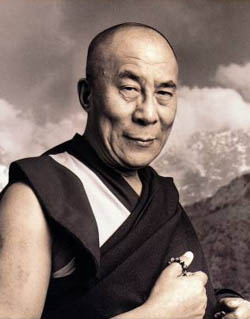

How would one reconcile with a news that was released 11 years ago, that �Dalai

Lama Group says it got money from CIA� (New York Times, Oct.2, 1998).

Before I cover the theatrics and economics of two Sinhala Buddhist monks,

Mapitigama Buddharakkhita Thero (1921-1967) and Talduwe Somarama Thero

(1915-1962), I provide the complete text of this 1998 New York Times

story for the benefit of those who had missed it, for its

topical interest..

�The Dalai Lama�s administration acknowledged today that it had received $1.7

million a year in the 1960s from the Central Intelligence Agency, but denied

reports that the Tibetan leader benefited personally from an annual subsidy of

$180,000. The money allocated for the resistance movement was spent on training

volunteers and paying for guerrilla operations against the Chinese, the Tibetan

government-in-exile said in a statement. It added that the subsidy earmarked for

the Dalai Lama was spent on setting up offices in Geneva and New York and on

international lobbying. The Dalai Lama, 63, a revered spiritual leader both in

his Himalayan homeland and in Western nations, fled Tibet in 1959 after a failed

uprising against a Chinese military occupation, which began in 1950. The

decade-long covert program to support the Tibetan independence movement was part

of the CIA�s worldwide effort to undermine Communist governments, particularly

in the Soviet Union and China.� �The Dalai Lama�s administration acknowledged today that it had received $1.7

million a year in the 1960s from the Central Intelligence Agency, but denied

reports that the Tibetan leader benefited personally from an annual subsidy of

$180,000. The money allocated for the resistance movement was spent on training

volunteers and paying for guerrilla operations against the Chinese, the Tibetan

government-in-exile said in a statement. It added that the subsidy earmarked for

the Dalai Lama was spent on setting up offices in Geneva and New York and on

international lobbying. The Dalai Lama, 63, a revered spiritual leader both in

his Himalayan homeland and in Western nations, fled Tibet in 1959 after a failed

uprising against a Chinese military occupation, which began in 1950. The

decade-long covert program to support the Tibetan independence movement was part

of the CIA�s worldwide effort to undermine Communist governments, particularly

in the Soviet Union and China.�

Now, here is a poser: it may not be inappropriate to postulate, considering the

year (1959) and the then Solomon Bandaranaike�s pro-Left government in Ceylon

installed in 1956, whether the Ceylonese equivalent of Dalai Lama,

Buddharakkhita Thero might also have benefited from CIA�s interest in toppling a

Left-leaning primeminister in the Indian Ocean.

Has anyone taken the trouble to

look seriously into this problem? In the 50 years that have lapsed, SLFP founded

by Solomon Bandaranaike was in power for 27 years (1960-65, 1970-77 and

1994-2009). Those who succeeded the assassinated prime

minister (the widow, the

daughter and the current incumbent) were least bothered to dig into this issue.

I�m also of the opinion that the remaining 23 years, when UNP had power (1965-70

and 1977-94), the top dogs of that party wouldn�t have cared a tuppence to find

out what happened.

The Organization of the Sinhala Buddhist Sangha

For relevance on the number of Sinhala Buddhist monks and the caste-based

division amongst them circa 1950s-1960s, I provide below four chapters from a

study by Yale University�s Hans-Dieter Evers that appeared in 1967.

�Although the Sangha is a very important institution in modern Sinhalese society

and in Ceylonese politics, very little has been published about it so far. Even

in recent sociological studies on Sinhalese religion the Buddhist monks have

received only limited attention. There are, however, two studies on the modern

Sangha written by Indologists (Bechart 1966 and Bareau 1957). Bechert�s recent

publication is the most comprehensive study of modern Theravada Buddhism and its

social and political role, and will most probably remain for a long period the

basic handbook for field research on Buddhism in Ceylon.

The Sangha of Ceylon is divided into three �orders� (nikaya): the Siam

Nikaya, the Amarapura Nikaya and the Ramana Nikaya. Each of these orders has in

the course of history been further subdivided into �chapters�, each of which is

headed by a Mahanayaka Thero. The Siam Nikaya is divided into six chapters, the

Amarapura Nikaya into at least 27 chapters, and the Ramana Nikaya into two

chapters. Most of the chapters have established and maintain a separate

tradition of higher ordination (upasampada).

The process of fission is still going on, officially because of doctrinal

disputes, usually on minor vinaya rules. In fact, however, most of the

subgroups have been formed either on caste lines, or on account of power

struggles within the Nikayas. There is no central authority or head of the whole

Sangha like the Sangharaja in Thailand. The situation is indeed far more complex

than is usually assumed in the existing literature.

The total number of monks is difficult to ascertain, for the official register

of bhikkus and samaneras in the Registrar General�s Office in Colombo is

incomplete and not up to date. Bechert estimates a total of about 17,000 monks,

out of which about 11,000 to 12,000 belong to the Siam Nikaya, about 3,000

belong to the Amarapura Nikaya, and about 2,000 to the Ramana Nikaya.�

On the �order� affiliation of assassin Talduwe Somarama Thero, author Lucian

Weeramantry had recorded, �Somarama belonged to the Malwatte chapter of the

Siamese Sect. The Malwatte chapter itself consisted of monks from the Vidyodaya

Pirivena and the Vidyalanka Pirivena. [A pirivena is a seminary of training

school for monks.] Somarama was from the Vidyodaya Pirivena.� [page 49] No

details were provided by Weeramantry on the �order� affiliation of prime

conspirator Mapitigama Buddharakkhita Thero.

Mapitigama Buddharakkhitha Thero and Talduwe Somarama Thero

One of primeminister Solomon Bandaranaike�s jokes on the character of

Buddharakkhita Thero, the prime conspirator in the 1959 assassination, has

appeared in print. Yasmine Gooneratne (a kin of Bandaranaike) had recorded in

1986 that Bandaranaike had quipped to her father, on the temptations of monk�s

weakness for flesh as: �He fasts by day, and he feasts by night�.

A short biographical note on Buddharakkhita Thero appears in the volume 1 of

J.R.Jayewardene�s biography, authored by K.M. de Silva and Howard Wriggins. To

quote,

�Buddharakkhita, Bhikkhu Mapitigama, 1921-1967: head of Kelaniya vihara 1947-59;

sentenced to death in 1961 for organizing murder of S.W.R.D.Bandaranaike. The

sentence was later changed to one of life imprisonment. He died in jail in

1967.�

A Time magazine (May 19, 1961) report provides a synopsis on the

theatrics and economics of the Bhikku duo, who dictated final terms to Solomon

Bandaranaike.

�Two years ago, Ceylon�s primeminister Solomon West Ridgeway Dias Badaranaike

bowed respectfully before a Buddhist monk among the crowd of petitioners

gathered on his veranda, in return got a blast of four bullets in his body. He

clung to life long enough to utter a last request. �I appeal to all concerned to

show compassion to this man and not to try and wreak vengeance on him�, he said,

and died.

Disregarding �Banda�s dying wish, a Ceylon judge last week sentenced Talduwe

Somarama, 45, to death. But the trial had proved that Somarama had been only the

triggerman; the instigator and chief plotter had been Mapitigama Buddharakitha,

41, high priest of the Kelaniya temple outside Colombo.

High priest Buddharakitha was clearly a man who was more interested in power

than religion. In 1956, when Bandaranaike was running for election,

Buddharakitha organized the United Monks� Front, which went scuttling off to the

hustings to recommend Banda and his Freedom Party, on the grounds that Banda

promised to give Buddhism its �rightful place� in Ceylon and to make Sinhala,

the tongue spoken by most Ceylonese Buddhists, the official language of the

land.

Banda won the election and became primeminister. In token of his gratitude, he

took his Cabinet to Buddharakitha�s temple for the customary post-inaugural

rites. He also gave the post of Minister of Health to Buddharakitha�s intimate

friend, the handsome widow Vimala Wijewardene, then 47. But when the high priest

demanded a $6,000,000 government contract for the construction of a sugar

factory and government concessions for a shipping company he planned to set up,

Banda balked. Buddharakitha, who had reveled in his position as kingmaker, felt

that he had been publicly humiliated. He decided to put Banda out of the way.

Casting about for a triggerman, he happened on Talduwe Somarama, who was both a

monk and a practicing ophthalmologist. As a Buddhist, Somarama was exasperated

at the primeminister�s delay in fulfilling his campaign promises to Buddhism. As

an ophthalmologist, he was anxious to have his contract at the State Indigenous

Hospital renewed, and therefore needed Buddharakitha�s good offices, for the

widow Wijewardene had put the high priest on the hospital�s appointment board.

Plainly, Somarama was Buddharakitha�s man.

In a confession that he later disavowed, assassin Somarama straightforwardly

declared: �I have done this thing to a man who did me no wrong � for the sake of

my religion, my language and my race.� High Priest Buddharakitha truculently

declared that he had been railroaded. The judge unhesitatingly sentenced both

Somarama and Buddharakitha to hang.�

A short rejoinder in the Time magazine (July 13, 1962), noted:

�In

Colombo last week, a Buddhist monk and herbalist named Talduwe Somarama mounted

a prison scaffold and was hanged. Somarama�s crime: the 1959 assassination of

Ceylon�s primeminister Solomon W.R.D. Bandaranaike. In a confession he later

retracted, Somarama said he committed the deed because the prime minister

favored western medical techniques over Oriental herb medicine. Prison officials

reported that 24 hours before he was hanged, Somarama had himself baptized a

Christian so that he could ask God for the forgiveness of sin that cannot be

found in the Buddhist religion.�

In sum, the following aspects can be identified as Buddharakkitha Thero�s

penchant for theatrics. He,

(1) used disparaging epithets to prominent political figures of the day,

referring to the primeminister as Sevela (slimy) Banda. He also used the

term nondiya (cripple) to refer Reginald Gotabhaya Senanayake, the

minister and the then Member of parliament for Kelaniya constituency, in which

his temple was located.

(2) flaunted his paramour relationship with the woman politician and the then

Minister of Health, Vimala Wijewardene.

(3) flouted ostentious Buddhist clergy�s life style by traveling in car and even

visiting London for medical check up.

(4) had in his services, camp followers and acolytes, who called him as �Our

Emperor�.

Weeramantry�s book on Bandaranaike assassination, provide the following details

as well on the economics of the prime conspirator�s deeds:

(1) In the 1952 general election, for the Kelaniya constitutency where his

paramour Vimala Wijewardene contested on the SLFP ticket against the incumbent

J.R. Jayewardene (UNP), Buddharakkitha Thero had spent �50,000 to 60,000 rupees

on her election campaign� (page 33). J.R. Jayewardene won that election, by a

majority of over 6,235 votes.

(2) Then, in the 1956 general election, Buddharakkitha Thero had complained that

�though he had spent over 100,000 rupees on the SLFP election campaign, he

himself had derived no advantage from the victory of that party.� (page 33).

(3) Buddharakkitha Thero also felt that Solomon Bandaranaike was being misled by

two of his Cabinet colleagues (namely the Leftist Philip Gunawardena and the

then sitting MP for Kelaniya, R.G. Senanayake), and though he had spent about

100,000 rupees in floating a shipping company, he was not given contract �to

carry rice to Ceylon from Burma and Thailand� (page 34).

(4) Two days after the death of Bandaranaike, Buddharakkitha Thero was fuming at

R.G. Senanayake, the then Kelaniya MP, to a witness: �Look here, I find that

this nondiya is trying to implicate me (emphasis in the original) in the

murder of the primeminister. I shall break his legs and fling him into the

Kelani river.� (page 36).

For record, mention should be made about the personality of R.G. Senanayake

(1911-1970). A cousin of prime minister Dudley Senanayake, this R.G. Senanayake

was one of the anti-Tamil politicians of his day. In the 1956 general election,

he contested two constituencies (Kelaniya and Dambadeniya) and won in both. In

Kelaniya, as an Independent he defeated later President J.R. Jayewardene (UNP)

convincingly with a majority of over 22, 836 votes. He holds the Sri Lankan

record for representing two constituencies simultaneously. Later, before the

1970 general election, R.G. Senanayake formed his own racist Sinhala Mahajana

Pakshaya (SMP) and contested two constituencies (Dambadeniya and Trincomalee)

and lost in both. A recent account, published in Colombo Daily News

(Sept.25, 2009) present a positive spin on R.G. Senanayake�s career;

�RG was a

gentleman to the core; he was never hard on his opponents, even in hotly

contested issues and hotly debated matters. He never lost his composure. He

treated his opponents with the contempt they deserved, but always with a smile.

Arrogance and abhorrence were alien to him�He stands out as the one and only

person who stood up to JR [ayawardene] and cut him to size in the political

arena.�

From Tamil perspectives, I would infer that politicians R.G. Senanayake, J.R.

Jayewardene, Philip Gunawardena and Buddharakkitha Thero promoted anti-Tamil

racism for vote catching purposes. But hardly a significant difference could be

noted in the grades of racism exhibited by all.

Assassin Somarama Thero�s statement from the Dock

I provide below, excerpts from chapter 32 of Weeramantry�s book (pages 196-199).

I felt that his version on assassination deserves some highlight.

� �I was born in Talduwa,� he began, �and received my early education at the

Buddhist Mixed School, Dehiowita. At the Talduwa temple in the year 1929 I was

ordained a Buddhist monk. I then entered the Vidyalanka Pirivena (seminary),

where I continued my studies for five years. In 1935 I gained admission to the

Vidyodaya Pirivena. In the following year I received my higher ordination at the

Malwatte temple, but continued my studies at the Vidyodaya Pirivena till 1940.

From 1940-43 I was a resident monk at the Ihala Talduwa (Upper Talduwa) temple.

In 1943 I moved to another temple to study the treatment of eye diseases and was

a student there for a period of five years. For some months in 1948 I treated

free a number of eye patients at the Hendela Leper Asylum as a service to

suffering humanity. Thereafter I returned to the temple at Ihala Talduwa. There

I engaged myself so intensely in religious work that I was successful in

securing sufficient lay support to have a new temple by the name of Somaramaya

built near the Talduwa junction.

Like many other monks who were concerned with the country�s future, I now began

to interest myself in politics. In 1952 I participated in a number of election

meetings held in support of Mrs. Wimala Wijewardene, who was a contestant for

the Kelaniya seat in the House of Representatives. On some days I presided at as

many as seven or eight meetings which were held in different parts of the

constitutency. Mr. Bandaranaike himself spoke at many of those meetings.

In 1953 I interested myself in building a home for the aged and had the first

accused [Buddharakkhita Thero] elected patron of the society formed for the

purpose. I did so as he was a person actively interested in public service. Mr.

Bandaranaike himself was elected a lay patron of the society after he had sent

me a letter consenting to his election. I eventually had a leaflet distributed

giving the names of the office-bearers of the society and setting out its

objectives.

Towards the end of 1957, I was appointed a lecturer and eye specialist at the

College of Indigenous Medicine for the year 1958. The certificates given to me

by the principal of Vidyalankara Pirivena and by my tutor in ophthalmology

helped me to secure this appointment. A year after my appointment I was

requested by my patients and some other physicians to seek reappointment for the

following year. I agreed and was reappointed.

During the time I worked at the Ayurvedic College, I resided at Amara Vihare,

which was close to the College. In 1959 Rev. Boose Amarasiri, the chief

incumbent of that vihare, engaged himself in a fast as a protest against the

erection of a meat stall near the temple. I too with some other monks made

representations to the primeminister against the erection of that meat stall.

During the days of Rev. Amarasiri�s fast, I remember Rev. Buddharakkitha to have

visited Amara Vihare on two occasions in order to meet him.

Early in September 1959, some nurses at the Indigenous Hospital staged a fast by

way of protest against certain injustices they complained of. They fasted for a

whole day, but could not get their grievances redressed. I was in sympathy with

their demands and went along with some of their relatives to meet the

primeminister. With his help the nurses had their grievances redressed. I then

became that a move was afoot to dispense with their services. Once again some

other physicians and I made representations to the primeminister. The

representations related not only to the moves against the nurses, but to several

other problems and anomalies at the College of Indigenous Medicine as well as at

the hospital.�

Somarama was speaking without reference to notes. For a man on trial for his

life, he was, if not cool, certainly remarkably collected. At times he spoke

slowly and with deliberation. But when describing the happenings of September 25th

1959, and the injustices to which he said he had been subjected by the police,

he was visibly agitated. Still not once did he break down; not once did he

falter.

� �On the morning of September 25th 1959,� he continued, �I went to

meet the primeminister once again. I went to his residence in Rosmead Place and

occupied a seat at the end of the verandah. Shortly afterwards the primeminister

came out, spoke to a number of persons on the verandah and then came up to me

and inquired why I had come. I told him that I had come to remind him of certain

very important representations I had made relating to the affairs of the College

of Indigenous Medicine and the hospital attached to it. The primeminister wanted

me to set out the details in writing and hand them to the Hon. A.P. Jayasuriya

to look into the matter. I thanked him and took my leave. I turned away to

collect my handkerchief and my papers, which I had placed on the stool by the

chair I had occupied. I was now with my back to the verandah and facing the

garden. While collecting my papers, I heard two or three gunshots. Struck with

terror, I stood motionless for a moment. I saw two persons in robes and some

others rushing away towards the main gate. People were running wildly in all

directions. It is indeed difficult to describe the confusion that reigned. I

then turned around, but yet in great fright. I saw the primeminister hurry into

the house through the main door. He was bleeding. The next thing I noticed was a

pistol lying on the floor about three or four feet away from me. I picked it up

and rushed inside the house to hand it over to some responsible person, carrying

it in this fashion (He demonstrates).

As I rushed in, I exclaimed to the first person I encountered, �Someone has shot

with this and run away�. Hardly had I completed saying that, than he pounced on

me. I implored him to wait until I had related what had happened, but he paid no

heed. He struggled with me and I fell down. As I lay fallen, I was shot. I then

lost consciousness.

From the primeminister�s residence I was removed to the Harbour Police station

where I partially regained consciousness and realized that I was badly injured.

There I was detained for about 2 hours, during the course of which several

persons came up and spoke to me. I remember telling them that I did not know who

was responsible for the shooting. From there, I was removed to the General

Hospital��

The final comments made by Somarama Thero, as recorded by his counsel in the

book was:

�I did not shoot the primeminister. It is untrue that the 1st

and 2nd accused or either of them requested me to do so. If I said so

to the Magistrate, it is false. My statement to the Magistrate was not made of

my own free will. I am not guilty.� (page 202).

Conclusion

As assassinated Indian primeminister Indira Gandhi�s regime was fond of

proclaiming the �influence of foreign hands� during 1966-77 and 1980-84, my

interest in the assassination of Solomon Bandaranaike is piqued on the issue of

whether any �foreign hand� was involved or Buddharakkitha Thero and Somarama

Thero acted on their own, basically prompted by their theatrical and economical

interests. Considering the following facts that

(1) the CIA links to Dalai Lama

came into open in late 1990s

(2) Solomon Bandaranaike�s politics and actions of

1950s was decisively pro-Left, when such sentiments were allergic to American

interests in Asia

(3) the CIA involvement in the assassinations and

assassination attempts on political leaders who were pro-Left (such as Patrice

Lumumba, President Sukarno, Fidel Castro) during the period 1959 to 1962, have

been no secret now, it may be of interest to delve into still �confidential�

records maintained elsewhere whether Mapitigama Buddarakkitha Thero had any

direct or indirect contacts with international gumshoes.

That Buddarakkitha

Thero also died in prison (at a relatively young age of 46), when UNP (a

decisively pro-West) government was in power muddles this issue. Some deaths in

prison or under detention (like that of Jack Ruby in President Kennedy

assassination, or that of Slobodan Milosevic) always elicit suspicious

questions.

Cited References and other relevant sources on Bandaranaike

Anonymous: Banda avenged.

Time, May 19, 1961, p. 30.

Anonymous: To find forgiveness.

Time, July 13, 1962.

Anonymous: Dalai Lama group says it got money from CIA.

New York Times,

Oct.2, 1998.

Bartholomeusz, T: In defense of Dharma � Just-war ideology in Buddhist Sri

Lanka. Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 1999; 6(1): 1-16.

Clarance, W: Woolf and Bandaranaike: The ironies of federalism in Sri Lanka.

Political Quarterly, Oct. 2001; 72(4): 480-486.

De Silva K.M.: Sri Lanka � the Bandaranaikes in the island�s politics and public

life. Round Table, 1999; no. 350; 241-280.

De Silva, K.M. and Wriggins, H:

J.R. Jayewardene of Sri Lanka �a political

biography, vol.1 (1906-1956), University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1988.

Evers, H-D: Kinship and property rights in a Buddhist monastery in Central

Ceylon. American Anthropologist, Dec. 1967; 69(6): 703-710.

Fernando, W.A.S: Sitting on two chairs with one umbrella in hand.

Colombo

Daily News, Sept.25, 2009.

Juergensmeyer, M: What the Bhikku said � Reflections on the rise of militant

religious nationalism. Religion, 1990; 20: 53-75.

Gooneratne, Y:

Relative Merits �a personal memoir of the Bandaranaike Family

of Sri Lanka, C. Hurst & Co, London, 1986.

Kodikara, S.U: Major trends in Sri Lanka�s non-alignment policy after 1956.

Asian Survey, Dec. 1973; 13(12): 1121-1136.

Seneviratne, H.L: Buddhist monks and ethnic politics.

Anthropology Today,

April 2001; 17(2): 15-21.

Weeramantry, L.G:

Assassination of a Prime Minister � The Bandaranaike Murder

Case, Geneva, 1969.

|