International Relations

in THE AGE OF EMPIRE

Shanghaied -

Shanghai Cooperation

Organization & the US

Suzanne Nossel in

the New Republic

[Suzanne Nossel writes for the blog

http://democracyarsenal.org/

]

30 April 2007

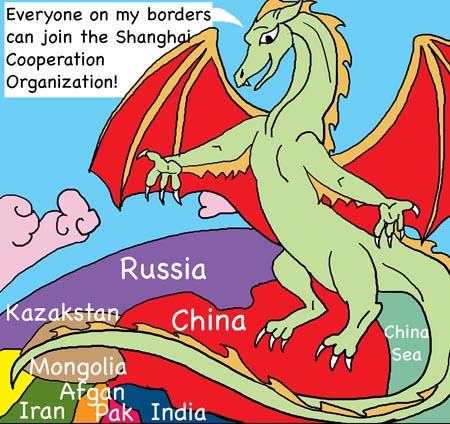

"...the

Shanghai Cooperation

Organization (SCO) - has emerged as a potential rival to Western groups.

Formed in June 2001 as a regional coalition between Russia, China,

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, the group endeavors to

become "a mature and confident regional force" focused on counter-terrorism,

trade, and other economic policies. Its influence may ultimately extend far

beyond its current member states... While the United States has chosen to

stand aloof from bodies like the ICC and HRC, at the SCO the tables are

turned: In 2006 the SCO denied America's request for observer status,

though India, Pakistan, Mongolia, and Iran all got the nod the previous

year. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal have lined up to participate next.

Such alliances are telling..By fostering collaboration on the exploitation

of the region's rich energy resources, the SCO could be in a position to

ensure China's privileged access to oil and gas. Cambridge academic David

Wall judged that its members' control over oil and gas reserves could make

the SCO into an "OPEC with bombs."" "...the

Shanghai Cooperation

Organization (SCO) - has emerged as a potential rival to Western groups.

Formed in June 2001 as a regional coalition between Russia, China,

Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, the group endeavors to

become "a mature and confident regional force" focused on counter-terrorism,

trade, and other economic policies. Its influence may ultimately extend far

beyond its current member states... While the United States has chosen to

stand aloof from bodies like the ICC and HRC, at the SCO the tables are

turned: In 2006 the SCO denied America's request for observer status,

though India, Pakistan, Mongolia, and Iran all got the nod the previous

year. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal have lined up to participate next.

Such alliances are telling..By fostering collaboration on the exploitation

of the region's rich energy resources, the SCO could be in a position to

ensure China's privileged access to oil and gas. Cambridge academic David

Wall judged that its members' control over oil and gas reserves could make

the SCO into an "OPEC with bombs.""

Comment by tamilnation.org

"Look back over the past, with its

changing empires that rose and fell, and you can foresee the

future, too." -

Marcus Aurelius,

1800 years ago - [see also

1.

The unipolar moment of US

supremacy has passed - Timothy Garton Ash, 24 January 2007 and

2.

Vladimir Putin, President of Russian Federation

on the Unipolar World, 10 February 2007]

A mong the lessons emerging from the Iraq war is a

growing consensus among American policy thinkers that Washington

needs to reinvigorate multilateral organizations, treaties, and

relationships. Recent studies by the Princeton Project on National

Security and others have concluded that the United States should

work with other groups to reform the United Nations, give NATO new

purpose, update the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, build new

regional coalitions in the Middle East and Asia, and forge a new

alliance of the world's democracies.

But restoring America's place atop the international order may not

be so simple. While American analysts are spelling these plans out

on paper, the international system has been evolving in ways that

could complicate America's ability to reengage multilaterally.

Not only has the go-it-alone ethos of the Bush years strained

relations with our allies, but rival nations have begun to wield

increased influence over organizations like the World Bank. Now,

too, a different breed of multilateral partnership - the

Shanghai

Cooperation Organization (SCO) - has emerged as a potential

rival to Western groups. Formed in June 2001 as a regional

coalition between Russia, China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan,

Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, the group endeavors to become "a

mature and confident regional force" focused on

counter-terrorism, trade, and other economic policies. Its

influence may ultimately extend far beyond its current member

states.

It's natural for Americans to envisage themselves at the helm of

a spiffed-up set of international institutions. After all,

Washington designed the United Nations and the financial

institutions conceived at Bretton Woods after World War II. Despite

all its grousing, the United States remains the U.N.'s largest donor

and loudest voice.

But multilateral organizations have not stood still since Bush

took office in 2001. For all the criticism of the U.N. from

conservatives, the body has won new credibility in the eyes of the

rest of the world for taking a stand against its most powerful

patron by refusing to authorize the Iraq war. The

International Criminal

Court (ICC) and the U.N.'s newly constituted

Human Rights

Council (HRC) have also moved ahead, led by other countries and

without U.S. participation.

While the United States has chosen to stand

aloof from bodies like the ICC and HRC, at the SCO the tables

are turned: In 2006 the SCO denied America's request for

observer status, though India, Pakistan, Mongolia, and Iran all

got the nod the previous year. Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, and Nepal

have lined up to participate next.

Such alliances are telling. Chinese President Hu Jintao declared

that the SCO is focused on "separatism, extremism and terrorism,"

problems that are of concern everywhere from Africa to Europe to

Washington, and it has brought together military leaders to plan

counter-terrorism exercises.

But, in practice, the organization has behaved as a front for

authoritarian regimes. Uzbekistan violently suppressed a political

demonstration in May 2005, massacring hundreds of unarmed

protesters. But, although the SCO's charter commits members to

"promote human rights and fundamental freedoms," the SCO's secretary

general rejected calls from human rights advocates to condemn the

bloodshed, declaring that the organization does not involve itself

in the internal affairs of its member states.

Thereafter, as tensions rose with Washington over the issue, the

SCO called (albeit indirectly) for the withdrawal of U.S. forces

stationed in Uzbekistan. Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad has

also used SCO gatherings as a rallying point for anti-American

sentiment, urging that the organization's members and observers draw

closer to one another and ward off foreign influences.

The SCO is likely to make its presence felt in other arenas as well.

By fostering collaboration on the exploitation of the region's rich

energy resources, the SCO could be in a position to ensure China's

privileged access to oil and gas. Cambridge academic David Wall

judged that its members' control over oil and gas reserves could

make the SCO into an "OPEC with bombs."

While the alarmism seems premature, it is clear that the SCO is

expanding its reach. It has also convened a conference of top judges

from member countries to discuss cross-border legal cooperation and

has even held a meeting with the European Union to talk about

partnership opportunities.

As it evolves, the composition of the SCO has the potential to

complicate U.S. efforts at alliance building. Among American

proponents of an alliance of democracies, for example, India is

viewed as a critical player whose support could help build

legitimacy for such a body outside the West. But Russia has been

courting Delhi heavily through a series of trilateral meetings

including Beijing in an effort to shape a more multipolar world less

dominated by Washington. If Delhi were to become a full member of

the SCO, that might signal its intent to align more closely with its

neighbors rather than casting its diplomatic lot with other

democracies.

If enough countries join the SCO, China and Russia will enjoy

increased political leverage. Some of the U.N.'s critics in the

United States have argued that beefing up and creating alternative

forums will provide an outlet by which the United States can

sidestep politically motivated vetoes in the U.N. Security Council

and nevertheless obtain international approval for, for example,

humanitarian interventions in places like Kosovo or Darfur. But as

the SCO grows, the United States will not be the only world power

that can play at this game. Beijing or Moscow could turn to their

organization to skirt a U.S. veto and secure at least the semblance

of an international imprimatur to, for example, crack down on

separatist groups.

For the last 60 years, the world's prominent multilateral

institutions have, at least on paper, reflected norms such as

transparency, respect for human rights, and democratic

participation. With China, Russia, Iran and other non-Western

countries stepping up to create and shape such institutions,

however, different sets of norms may prevail.

None of this suggests that Washington should back away from a push

to reinvigorate multilateral institutions or reassert its place

within them. But it does mean that doing so will require careful

attention to how dynamics have shifted while the Bush administration

looked the other way.

|