|

International

Relations

in THE AGE OF EMPIRE

Rebuilding America's Defenses

Strategy, Forces and

Resources for a New Century

A Report of The Project for the New American

Century

September 2000

Authors and Project

Participants

|

"...American land power is

the essential link in the chain that

translates U.S. military supremacy into

American geopolitical preeminence...

Elements of U.S. Army Europe should be

redeployed to Southeast Europe, while a

permanent unit should be based in the

Persian Gulf region...In Southeast Asia,

American forces are too sparse to address

rising security requirements adequately...

No U.S. strategy can constrain a Chinese

challenge to American regional leadership

if our security guarantees to Southeast

Asia are intermittent and U.S. military

presence a periodic affair. For this

reason, an increased naval presence in

Southeast Asia, while necessary, will not

be sufficient; as in the Balkans, relying

solely on allied forces or the rotation of

U.S. forces in stability operations not

only increases the stress on those forces

but undercuts the political goals of such

missions. For operational as well as

political reasons, stationing rapidly

mobile U.S. ground and air forces in the

region will be required...

...Since today's peace

is the unique product of American

preeminence, a failure to preserve that

preeminence allows others an opportunity to

shape the world in ways antithetical to

American interests and

principles...Global leadership is not

something exercised at our leisure, when

the mood strikes us or when our core

national security interests are directly

threatened; then it is already too late.

Rather, it is a choice whether or not to

maintain American military preeminence, to

secure American geopolitical leadership,

and to preserve the American

peace."

Contents

Full Report in PDF

Introduction

Key Findings

I. Why Another Defense Review?

II. Four Essential Missions

III. Repositioning Today's Force

IV. Rebuilding Today's Armed Forces

V. Creating Tomorrow's Dominant Force

VI. Defense Spending

Project Participants

|

Introduction

The Project for the New American

Century was established in the spring of 1997. From

its inception, the Project has been concerned with

the decline in the strength of America's defenses,

and in the problems this would create for the

exercise of American leadership around the globe

and, ultimately, for the preservation of peace.

Our concerns were reinforced by the

two congressionally-mandated defense studies that

appeared soon thereafter: the Pentagon's

Quadrennial Defense Review (May 1997) and the

report of the National Defense Panel (December

1997). Both studies assumed that U.S. defense

budgets would remain flat or continue to shrink. As

a result, the defense plans and recommendations

outlined in the two reports were fashioned with

such budget constraints in mind. Broadly speaking,

the QDR stressed current military requirements at

the expense of future defense needs, while the

NDP's report emphasized future needs by

underestimating today's defense

responsibilities.

Although the QDR and the report of

the NDP proposed different policies, they shared

one underlying feature: the gap between resources

and strategy should be resolved not by increasing

resources but by shortchanging strategy. America's

armed forces, it seemed, could either prepare for

the future by retreating from its role as the

essential defender of today's global security

order, or it could take care of current business

but be unprepared for tomorrow's threats and

tomorrow's battlefields. Either alternative seemed

to us shortsighted. The United States is the

world's only superpower, combining preeminent

military power, global technological leadership,

and the world's largest economy.

Moreover, America stands at the

head of a system of alliances which includes the

world's other leading democratic powers. At present

the United States faces no global rival.

America's grand strategy should aim

to preserve and extend this advantageous position

as far into the future as possible. There are,

however, potentially powerful states dissatisfied

with the current situation and eager to change it,

if they can, in directions that endanger the

relatively peaceful, prosperous and free condition

the world enjoys today. Up to now, they have been

deterred from doing so by the capability and global

presence of American military power.

| At present

the United States faces no global rival.

America's grand strategy should aim to

preserve and extend this advantageous

position as far into the future as possible.

|

But, as that power declines,

relatively and absolutely, the happy conditions

that follow from it will be inevitably undermined.

Preserving the desirable strategic situation in

which the United States now finds itself requires a

globally preeminent military capability both today

and in the future. But years of cuts in defense

spending have eroded the American military's combat

readiness, and put in jeopardy the Pentagon's plans

for maintaining military superiority in the years

ahead. Increasingly, the U.S. military has found

itself undermanned, inadequately equipped and

trained, straining to handle contingency

operations, and ill-prepared to adapt itself to the

revolution in military affairs. Without a

well-conceived defense policy and an appropriate

increase in defense spending -

the United States has been letting its ability to

take full advantage of the remarkable strategic

opportunity at hand slip away.

With this in mind, we began a

project in the spring of 1998 to examine the

country's defense plans and resource requirements.

We started from the premise that U.S. military

capabilities should be sufficient to support an

American grand strategy committed to building upon

this unprecedented opportunity. We did not accept

pre-ordained constraints that followed from

assumptions about what the country might or might

not be willing to expend on its defenses.

In broad terms, we saw the project

as building upon the defense strategy outlined by

the Cheney Defense Department in the waning days of

the Bush Administration. The Defense Policy

Guidance (DPG) drafted in the early months of 1992

provided a blueprint for maintaining U.S.

preeminence, precluding the rise of a great power

rival, and shaping the international security order

in line with American principles and interests.

Leaked before it had been formally approved, the

document was criticized as an effort by "cold

warriors" to keep defense spending high and cuts in

forces small despite the collapse of the Soviet

Union; not surprisingly, it was subsequently buried

by the new administration.

Although the experience of the past

eight years has modified our understanding of

particular military requirements for carrying out

such a strategy, the basic tenets of the DPG, in

our judgment, remain sound. And what Secretary

Cheney said at the time in response to the DPG's

critics remains true today: "We can either sustain

the [armed] forces we require and remain in a

position to help shape things for the better, or we

can throw that advantage away. [But] that would

only hasten the day when we face greater threats,

at higher costs and further risk to American

lives."

The project proceeded by holding a

series of seminars. We asked outstanding defense

specialists to write papers to explore a variety of

topics: the future missions and requirements of the

individual military services, the role of the

reserves, nuclear strategic doctrine and missile

defenses, the defense budget and prospects for

military modernization, the state (training and

readiness) of today's forces, the revolution in

military affairs, and defense-planning for theater

wars, small wars and constabulary operations. The

papers were circulated to a group of participants,

chosen for their experience and judgment in defense

affairs. (The list of participants may be found at

the end of this report.) Each paper then became the

basis for discussion and debate.

Our goal was to use the papers to

assist deliberation, to generate and test ideas,

and to assist us in developing our final report.

While each paper took as its starting point a

shared strategic point of view, we made no attempt

to dictate the views or direction of the individual

papers. We wanted as full and as diverse a

discussion as possible. Our report borrows heavily

from those deliberations. But we did not ask

seminar participants to "sign-off" on the final

report. We wanted frank discussions and we sought

to avoid the pitfalls of trying to produce a

consensual but bland product. We wanted to try to

define and describe a defense strategy that is

honest, thoughtful, bold, internally consistent and

clear. And we wanted to spark a serious and

informed discussion, the essential first step for

reaching sound conclusions and for gaining public

support.

New circumstances make us think

that the report might have a more receptive

audience now than in recent years. For the first

time since the late 1960s the federal government is

running a surplus. For most of the 1990s, Congress

and the White House gave balancing the federal

budget a higher priority than funding national

security. In fact, to a significant degree, the

budget was balanced by a combination of increased

tax revenues and cuts in defense spending. The

surplus expected in federal revenues over the next

decade, however, removes any need to hold defense

spending to some preconceived low level.

Moreover, the American public and

its elected representatives have become

increasingly aware of the declining state of the

U.S. military. News stories, Pentagon reports,

congressional testimony and anecdotal accounts from

members of the armed services paint a disturbing

picture of an American military that is troubled by

poor enlistment and retention rates, shoddy

housing, a shortage of spare parts and weapons, and

diminishing combat readiness. Finally, this report

comes after a decade's worth of experience in

dealing with the post-Cold War world. Previous

efforts to fashion a defense strategy that would

make sense for today's security environment were

forced to work from many untested assumptions about

the nature of a world without a superpower rival.

We have a much better idea today of what our

responsibilities are, what the threats to us might

be in this new security environment, and what it

will take to secure the relative peace and

stability. We believe our report reflects and

benefits from that decade's worth of

experience.

Our report is published in a

presidential election year. The new administration

will need to produce a second Quadrennial Defense

Review shortly after it takes office. We hope that

the Project's report will be useful as a road map

for the nation's immediate and future defense

plans. We believe we have set forth a defense

program that is justified by the evidence, rests on

an honest examination of the problems and

possibilities, and does not flinch from facing the

true cost of security. We hope it will inspire

careful consideration and serious discussion. The

post-Cold War world will not remain a relatively

peaceful place if we continue to neglect foreign

and defense matters. But serious attention, careful

thought, and the willingness to devote adequate

resources to maintaining America's military

strength can make the world safer and American

strategic interests more secure now and in the

future.

Key Findings

This report proceeds from the

belief that America should seek to preserve and

extend its position of global leadership by

maintaining the preeminence of U.S. military

forces. Today, the United States has an

unprecedented strategic opportunity. It faces no

immediate great-power challenge; it is blessed with

wealthy, powerful and democratic allies in every

part of the world; it is in the midst of the

longest economic expansion in its history; and its

political and economic principles are almost

universally embraced. At no time in history has the

international security order been as conducive to

American interests and ideals. The challenge for

the coming century is to preserve and enhance this

"American peace."

Yet unless the United States

maintains sufficient military strength, this

opportunity will be lost. And in fact, over the

past decade, the failure to establish a security

strategy responsive to new realities and to provide

adequate resources for the full range of missions

needed to exercise U.S. global leadership has

placed the American peace at growing risk. This

report attempts to define those requirements. In

particular, we need to:

ESTABLISH FOUR CORE MISSIONS for

U.S. military forces:

• defend the American

homeland;

• fight and decisively win multiple,

simultaneous major theater wars;

• perform the "constabulary" duties

associated with shaping the security environment

in critical regions;

• transform U.S. forces to exploit the

"revolution in military affairs;"

To carry out these core missions, we need to

provide sufficient force and budgetary

allocations. In particular, the United States

must:

MAINTAIN NUCLEAR STRATEGIC

SUPERIORITY, basing the U.S. nuclear deterrent

upon a global, nuclear net assessment that weighs

the full range of current and emerging threats,

not merely the U.S.-Russia balance.

RESTORE THE PERSONNEL STRENGTH of

today's force to roughly the levels anticipated

in the "Base Force" outlined by the Bush

Administration, an increase in active-duty

strength from 1.4 million to 1.6 million.

REPOSITION U.S. FORCES to respond

to 21st century strategic realities by shifting

permanently-based forces to Southeast Europe and

Southeast Asia, and by changing naval deployment

patterns to reflect growing U.S. strategic

concerns in East Asia.

MODERNIZE CURRENT U.S. FORCES

SELECTIVELY, proceeding with the F-22 program

while increasing purchases of lift, electronic

support and other aircraft; expanding submarine

and surface combatant fleets; purchasing Comanche

helicopters and medium-weight ground vehicles for

the Army, and the V-22 Osprey "tilt-rotor"

aircraft for the Marine Corps.

CANCEL "ROADBLOCK" PROGRAMS such

as the Joint Strike Fighter, CVX aircraft

carrier, and Crusader howitzer system that would

absorb exorbitant amounts of Pentagon funding

while providing limited improvements to current

capabilities. Savings from these canceled

programs should be used to spur the process of

military transformation.

DEVELOP AND DEPLOY GLOBAL MISSILE

DEFENSES to defend the American homeland and

American allies, and to provide a secure basis

for U.S. power projection around the world.

CONTROL THE NEW "INTERNATIONAL

COMMONS" OF SPACE AND "CYBERSPACE," and pave the

way for the creation of a new military service -

U.S. Space Forces - with the mission of space

control.

EXPLOIT THE "REVOLUTION IN

MILITARY AFFAIRS" to insure the long-term

superiority of U.S. conventional forces.

Establish a two-stage transformation process

which

• maximizes the value of

current weapons systems through the application

of advanced technologies, and,

• produces more profound improvements in

military capabilities, encourages competition

between single services and joint-service

experimentation efforts.

INCREASE DEFENSE SPENDING

gradually to a minimum level of 3.5 to 3.8

percent of gross domestic product, adding $15

billion to $20 billion to total defense spending

annually.

Fulfilling these requirements is

essential if America is to retain its militarily

dominant status for the coming decades. Conversely,

the failure to meet any of these needs must result

in some form of strategic retreat. At current

levels of defense spending, the only option is to

try ineffectually to "manage" increasingly large

risks: paying for today's needs by shortchanging

tomorrow's; withdrawing from constabulary missions

to retain strength for large-scale wars; "choosing"

between presence in Europe or presence in Asia; and

so on. These are bad choices. They are also false

economies. The "savings" from withdrawing from the

Balkans, for example, will not free up anywhere

near the magnitude of funds needed for military

modernization or transformation. But these are

false economies in other, more profound ways as

well. The true cost of not meeting our defense

requirements will be a lessened capacity for

American global leadership and, ultimately, the

loss of a global security order that is uniquely

friendly to American principles and prosperity.

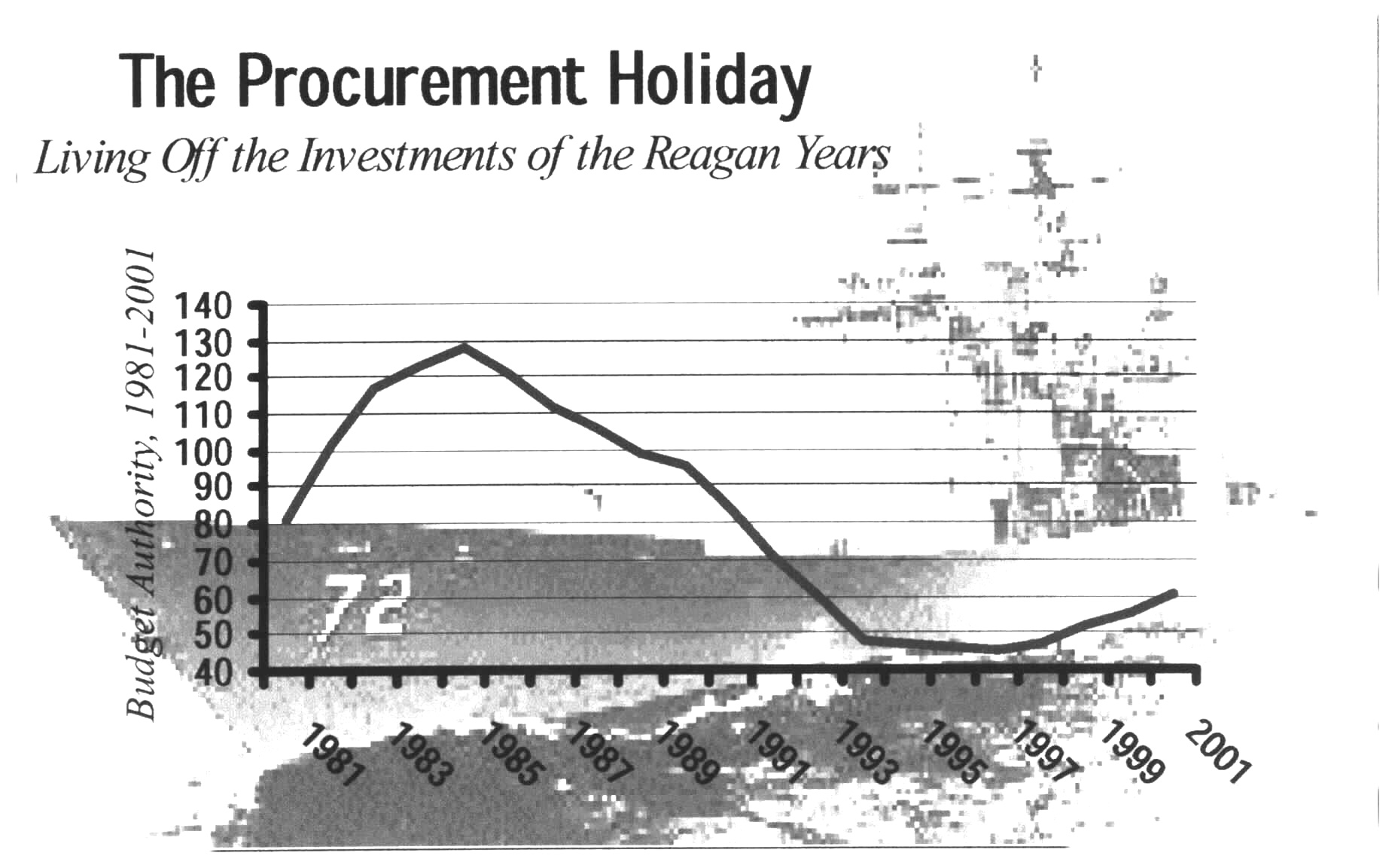

Defense Spending

Use of the post- Cold War "peace

dividend" to balance the federal budget has created

a "defense deficit" totaling tens of billions of

dollars annually.

What, then, is the price of

continued American geopolitical leadership and

military preeminence?

A finely detailed answer is beyond

the scope of this study. Too many of the force

posture and service structure recommendations above

involve factors that current defense planning has

not accounted for. Suffice it to say that an

expanded American security perimeter, new

technologies and weapons systems including robust

missile defenses, new kinds of organizations and

operating concepts, new bases and the like will not

come cheap. Nonetheless, this section will attempt

to establish broad guidelines for a level of

defense spending sufficient to maintain America

military preeminence.

In recent years, a variety of

analyses of the mismatch between the Clinton

Administration's proposed defense budgets and

defense program have appeared. The estimates all

agree that the Clinton program is underfunded; the

differences lie in gauging the amount of the

shortage and range from about $26 billion annually

to $100 billion annually, with the higher numbers

representing the more rigorous analyses.

Trends in

Defense Spending

For the first time in 15 years, the

2001 defense budget may reflect a modest real

increase in U.S. defense spending. Both President

Clinton's defense budget request and the figures

contained in the congressional budget resolution

would halt the slide in defense budgets. Yet the

extended paying of the "peace dividend" - and the

creation of today's federal budget surplus, the

product of increased tax revenues and reduced

defense spending - has created a severe "defense

deficit," totaling tens of billions of dollars

annually.

The Congress has been complicit in

this defense decline. In the first years of the

administration, Congress acquiesced in the sharp

reductions made by the Clinton Administration from

the amount projected in the final Bush defense

plan.

Since the Republicans won control

of Congress in 1994, very slight additions have

been made to administration defense requests, yet

none has been able to turn around the pattern of

defense decline until this year.

Even these increases were achieved

by the use of accounting gimmicks that allow the

government to circumvent the limitations of the

1997 balanced budget agreement.

Through all the accounting

gimmicks, defense spending has been almost

perfectly flat - indeed, the totals have been less

than $1 billion apart - for the past four years.

The steepest declines in defense spending were

accomplished during the early years of the Clinton

Administration, when defense spending levels fell

from about $339 billion in 1992 to $277 billion in

1996. The cumulative effects of reduced defense

spending over a decade or more have been even more

severe. A recent study by the Center for Strategic

and International Studies, Avoiding the Defense

Train Wreck in the New Millennium, compared the

final Bush defense plan, covering 1994 through

1999, with the defense plan of the Clinton

Administration and found that a combination of

budget changes and internal Pentagon actions had

resulted in a net reduction in defense spending of

$162 billion from the Bush plan to the Clinton

plan. Congressional budget increases and

supplemental appropriations requests added back

about $52 billion, but that spending for the most

part covered the cost of contingency operations and

other readiness shortfalls - it did not buy back

much of the modernization that was deferred.

Compared to Bush-era budgets, the Clinton

Administration reduced procurement spending an

average of $40 billion annually. During the period

from 1993 to 2000, deferred procurements - the

infamous "procurement bow wave" - more than doubled

from previous levels to $426 billion, according to

the report.

The CSIS report is but the most

recent in a series of reports gauging the size of

the mismatch between current long-term defense

plans and budgets. The Congressional Budget

Office's latest estimate of the annual mismatch is

at least $90 billion. Even the 1997 Quadrennial

Defense Review itself allowed for a

$12-to-15-billion annual funding shortfall; now the

Joint Chiefs of Staff, according to news reports,

are insisting on a $30-billion-per-year increase in

defense spending. In 1997 the Center for Strategic

and Budgetary Assessments calculated the annual

shortfall at approximately $26 billion and has now

increased its total to $50 billion; analyst Michael

O'Hanlon of the Brookings Institution pegs that gap

at $27 billion, at a minimum. Perhaps more

important than the question of which of these

estimates best calculates the amount of the current

defense shortfall is the question of what costs are

not captured. All of these estimates measure the

gap between current defense plans and programs and

current budgets; they make no allowance for the new

missions and needs of the post-Cold War world. They

do not capture the costs of deploying effective

missile defenses. They do not account for the costs

of constabulary missions. They do not consider the

costs of transformation. Nor do they calculate the

costs of the other recommendations of this report,

such as strengthening, reconfiguring, and

repositioning today's force.

In fact, the best way to measure

defense spending over longer periods of time is as

a portion of national wealth and federal spending.

By these metrics, defense budgets have continued to

decline even as Americans have become more

prosperous in recent years. The defense budget now

totals less than 3 percent of the gross domestic

product - the lowest level of U.S. defense spending

since the Depression. Defense accounts for about 15

percent of federal spending - slightly more than

interest on the debt, and less than one third of

the amount spent on Social Security, Medicare and

other entitlement programs, which account for 54

percent of federal spending. As the annual federal

budget has moved from deficit to surplus and more

resources have become available, there has been no

serious or sustained effort to recapitalize U.S.

armed forces.

As troublesome as the trends of the

past decade have been, as inadequate as current

budgets are, the longer-term future is more

troubling still. If current spending levels are

maintained, by some projections, the amount of the

defense shortfall will be almost as large as the

defense budget itself by 2020 - 2.3 percent

compared to 2.4 percent of gross domestic product.

In particular, as modernization spending slips

farther and farther behind requirements, the

procurement bow wave will reach tsunami

proportions, says CSIS: "By continuing to kick the

can down the road, the military departments will,

in effect, create a situation in which they require

$4.4 trillion in procurement dollars" from 2006

through 2020 to maintain the current force.

After 2010 - seemingly a long way

off but well within traditional defense planning

horizons - the outlook for increased military

spending under current plans becomes even more

doubtful. In the coming decades, the network of

social entitlement programs, particularly Social

Security, will generate a further squeeze on other

federal spending programs. If defense budgets

remain at projected levels, America's global

military preeminence will be impossible to

maintain, as will the world order that is secured

by that preeminence.

Budgets and

the Strategy Of Retreat

Recent defense reviews, and the

1997 Quadrennial Defense Review and the

accompanying report of the National Defense Panel

especially, have framed the dilemma facing the

Pentagon and the nation as a whole as a question of

risk. At current and planned spending levels, the

United States can preserve current forces and

capabilities to execute current missions and

sacrifice modernization, innovation and

transformation, or it can reduce personnel strength

and force structure further to pay for new weapons

and forces. Despite the QDR's rhetoric about

shaping the current strategic environment,

responding to crises and preparing now for an

uncertain future,

If defense spending remains at

current levels, U.S. forces will soon be too old or

too small. the Clinton Administration's defense

plans continue to place a higher priority on

immediate needs than on preparing for a more

challenging technological or geo-political future;

as indicated in the force posture section above,

the QDR retains the two-war standard as the central

feature of defense planning and the sine qua non of

America's claim to be a global superpower. The

National Defense Panel, with its call for a

"transformation strategy," argued that the

"priority must go to the future." The twowar

standard, in the panel's assessment, "has become a

means of justifying current forces. This approach

focuses resources on a lowprobability scenario,

which consumes funds that could be used to reduce

risk to our longterm security."

Again, the CSIS study's

affordability assessments suggest the trade-offs

between manpower and force structure that must be

made under current budget constraints. For example,

CSIS estimates that the cost of modernizing the

current 1.37 millionman force would require

procurement spending of $164 billion per year.

While we might not agree with every aspect of the

methodology underlying this calculation, the larger

point is clear: if defense spending remains at

current levels, as current plans under the QDR

assume, the Pentagon would only be able to

modernize a little more than half the force. Under

this scenario, U.S. armed forces would become

increasingly obsolescent, expensive to operate and

outclassed on the battlefield. As the report

concludes, "U.S. military forces will lose their

credibility both at home and abroad regarding their

size, age, and technological capabilities for

carrying out the national military strategy."

Conversely, adopting the National

Defense Panel approach of accepting greater risk

today while preparing for the future would require

significant further cuts in the size of U.S. armed

forces. According to CSIS, a shift in resources

that would up the rate of modernized equipment to

76 percent - not a figure specified by the NDP but

one not inconsistent with that general approach -

would require reducing the total strength of U.S.

forces to just 1 million, again assuming 3 percent

of GDP were devoted to defense spending. Thus, at

current spending levels the Pentagon must choose

between force structure and modernization.

When it is recalled that a

projection of defense spending levels at 3 percent

of GDP represents the most optimistic assumption

about current Pentagon plans, the horns of this

dilemma appear sharper still: at these levels, U.S.

forces soon will be too old or too small. Following

the administration's "live for today" path will

ensure that, in some future high-intensity war,

U.S. forces will lack the cutting-edge technologies

that they have come to rely on. Following the NDP's

"prepare for tomorrow" path, U.S. forces will lack

the manpower needed to conduct their current

missions. From constabulary duties to the conduct

of major theater wars, the ability to defend

current U.S. security interests will be placed at

growing risk.

In a larger sense, these two

approaches differ merely about the nature and

timing of a strategy of American retreat. By

committing forces to the Balkans, maintaining U.S.

presence in the Persian Gulf, and by responding to

Chinese threats to Taiwan and sending peacekeepers

to East Timor, the Clinton Administration has,

haltingly, incrementally and often fecklessly,

taken some of the necessary steps for strengthening

the new American security perimeter. But by holding

defense spending and military strength to their

current levels, the administration has compromised

the nation's ability to fight large-scale wars

today and consumed the investments that ought to

have been made to preserve American military

preeminence tomorrow.

The reckoning for such a strategy

will come when U.S. forces are unable to meet the

demands placed upon them. This may happen when they

take on one mission too many - if, say, NATO's role

in the Balkans expands, or U.S troops enforce a

demilitarized zone on the Golan Heights - and a

major theater war breaks out. Or, it may happen

when two major theater wars occur nearly

simultaneously. Or it may happen when a new great

power - a rising China - seeks to challenge

American interests and allies in an important

region.

By contrast, a strategy that

sacrifices force structure and current readiness

for future transformation will leave American armed

forces unable to meet today's missions and

commitments.

Since

today's peace is the unique product of American

preeminence, a failure to preserve that

preeminence allows others an opportunity to shape

the world in ways antithetical to American

interests and principles.

The price of American preeminence

is that, just as it was actively obtained, it must

be actively maintained. But as service chiefs and

other senior military leaders readily admit,

today's forces are barely adequate to maintain the

rotation of units to the myriad peacekeeping and

other constabulary duties they face while keeping

adequate forces for a single major theater war in

reserve.

An active-duty force reduced by

another 300,000 to 400,000 - almost another 30

percent cut from current levels and a total

reduction of more than half from Cold-War levels -

to free up funds for modernization and

transformation would be clearly inadequate to the

demands of today's missions and national military

strategy. If the United States withdrew forces from

the Balkans, for example, it is unlikely that the

rest of NATO would be able to long pick up the

slack; conversely, such a withdrawal would provoke

a political crisis within NATO that would certainly

result in the end of American leadership within

NATO; it might well spell the end of the alliance

itself.

Likewise,

terminating the no-flyzones over Iraq would call

America's position as guarantor of security in

the Persian Gulf into question; the reaction

would be the same in East Asia following a

withdrawal of U.S. forces or a lowering of

American military presence.

The consequences sketched by the

Quadrennial Defense Review regarding a retreat from

a two-war capability would inexorably come to pass:

allies and adversaries alike would begin to hedge

against American retreat and discount American

security guarantees. At current budget levels, a

modernization or transformation strategy is in

danger of becoming a "no-war" strategy. While the

American peace might not come to a catastrophic

end, it would quickly begin to unravel; the result

would be much the same in time.

The Price of

American Preeminence

As admitted above, calculating the

exact price of armed forces capable of maintaining

American military preeminence today and extending

it into the future requires more detailed analysis

than this broad study can provide. We have

advocated a force posture and service structure

that diverges significantly both from current plans

and alternatives advanced in other studies. We

believe it is necessary to increase slightly the

personnel strength of U.S. forces - many of the

missions associated with patrolling the expanding

American security perimeter are manpower-intensive,

and planning for major theater wars must include

the ability for politically decisive campaigns

including extended post-combat stability

operations. Also, this expanding perimeter argues

strongly for new overseas bases and forward

operating locations to facilitate American

political and military operations around the

world.

At the same time, we have argued

that established constabulary missions can be made

less burdensome on soldiers, sailors, airmen and

Marines and less burdensome on overall U.S. force

structure by a more sensible forward-basing

posture; long-term security commitments should not

be supported by the debilitating, short-term

rotation of units except as a last resort. In

Europe, the Persian Gulf and East Asia, enduring

U.S. security interests argue forcefully for an

enduring American military presence. Pentagon

policy-makers must adjust their plans to

accommodate these realities and to reduce the wear

and tear on service personnel. We have also argued

that the services can begin now to create new, more

flexible units and military organizations that may,

over time, prove to be smaller than current

organizations, even for peacekeeping and

constabulary operations.

Even as American military forces

patrol an expanding security perimeter, we believe

it essential to retain sufficient forces based in

the continental United States capable of rapid

reinforcement and, if needed, applying massive

combat power to stabilize a region in crisis or to

bring a war to a successful conclusion. There

should be a strong strategic synergy between U.S.

forces overseas and in a reinforcing posture: units

operating abroad are an indication of American

geopolitical interests and leadership, provide

significant military power to shape events and, in

wartime, create the conditions for victory when

reinforced. Conversely, maintaining the ability to

deliver an unquestioned "knockout punch" through

the rapid introduction of stateside units will

increase the shaping power of forces operating

overseas and the vitality of our alliances. In sum,

we see an enduring need for large-scale American

forces.

But while arguing for improvements

in today's armed services and force posture, we are

unwilling to sacrifice the ability to maintain

preeminence in the longer term. If the United

States is to maintain its preeminence - and the

military revolution now underway is already an

American-led revolution - the Pentagon must begin

in earnest to transform U.S. military forces.

The program we advocate - one that

would provide America with forces to meet the

strategic demands of the world's sole superpower -

requires budget levels to be increased to 3.5 to

3.8 percent of the GDP.

We have argued that this

transformation mission is yet another new mission,

as compelling as the need to maintain European

stability in the Balkans, prepare for large,

theater wars or any other of today's missions. This

is an effort that involves more than new weaponry

or technologies. It requires experimental units

free to invent new concepts of operation, new

doctrines, new tactics. It will require years, even

decades, to fully grasp and implement such changes,

and will surely involve mistakes and

inefficiencies. Yet the maintenance of the American

peace requires that American forces be preeminent

when they are called upon to face very different

adversaries in the future.

Finally, we have argued that we

must restore the foundation of American security

and the basis for U.S. military operations abroad

by improving our homeland defenses. The current

American peace will be short-lived if the United

States becomes vulnerable to rogue powers with

small, inexpensive arsenals of ballistic missiles

and nuclear warheads or other weapons of mass

destruction. We cannot allow North Korea, Iran,

Iraq or similar states to undermine American

leadership, intimidate American allies or threaten

the American homeland itself. The blessings of the

American peace, purchased at fearful cost and a

century of effort, should not be so trivially

squandered.

Taken all in all, the force posture

and service structure we advocate differ enough

from current plans that estimating its costs

precisely based upon known budget plans is unsound.

Likewise, generating independent cost analyses is

beyond the scope of this report and would be based

upon great political and technological

uncertainties - any detailed assumptions about the

cost of new overseas bases or revolutionary

weaponry are bound to be highly speculative absent

rigorous net assessments and program analysis.

Nevertheless, we believe that, over time, the

program we advocate would require budgets roughly

equal to those necessary to fully fund the QDR

force - a minimum level of 3.5 to 3.8 percent of

gross domestic product. A sensible plan would add

$15 billion to $20 billion to total defense

spending annually through the Future Years Defense

Program; this would result in a defense "topline"

increase of $75 billion to $100 billion over that

period, a small percentage of the $700 billion on

budget surplus now projected for that same period.

We believe that the new president should commit his

administration to a plan to achieve that level of

spending within four years.

In its simplest terms, our intent

is to provide forces sufficient to meet today's

missions as effectively and efficiently as

possible, while readying U.S. armed forces for the

likely new missions of the future. Thus, the

defense program described above would preserve

current force structure while improving its

readiness, better posturing it for its current

missions, and making selected investments in

modernization. At the same time, we would shift the

weight of defense recapitalization efforts to

transforming U.S. forces for the decades to come.

At four cents on the dollar of America's national

wealth, this is an affordable program. It is also a

wise program.

Only such a force posture, service

structure and level of defense spending will

provide America and its leaders with a variety of

forces to meet the strategic demands of the world's

sole superpower. Keeping the American peace

requires the U.S. military to undertake a broad

array of missions today and rise to very different

challenges tomorrow, but there can be no retreat

from these missions without compromising American

leadership and the benevolent order it secures.

This is the choice we face. It is not a choice

between preeminence today and preeminence tomorrow.

Global leadership is not

something exercised at our leisure, when the mood

strikes us or when our core national security

interests are directly threatened; then it is

already too late. Rather, it is a choice whether

or not to maintain American military preeminence,

to secure American geopolitical leadership, and

to preserve the American peace.

Authors:

Project

Co-Chairmen: Donald Kagan, Gary Schmitt, ,

Principal Author: Thomas Donnelly

Project

Participants:

Roger Barnett,

U.S. Naval War College;

Alvin Bernstein, National Defense University;

Stephen Cambone, National Defense University;

Eliot Cohen, Nitze School of Advanced

International Studies, Johns Hopkins

University;

Devon Gaffney Cross, Donors' Forum for

International Affairs;

Thomas Donnelly, Project for the New American

Century;

David Epstein, Office of Secretary of Defense,

Net Assessment;

David Fautua, Lt. Col., U.S. Army;

Dan Goure, Center for Strategic and

International Studies;

Donald Kagan, Yale University;

Fred Kagan, U. S. Military Academy at West

Point;

Robert Kagan, Carnegie Endowment for

International Peace;

Robert Killebrew, Col., USA (Ret.);

William Kristol, The Weekly Standard;

Mark Lagon, Senate Foreign Relations Committee;

James Lasswell, GAMA Corporation;

I. Lewis Libby, Dechert Price & Rhoads;

Robert Martinage, Center for Strategic and

Budgetary Assessment;

Phil Meilinger.,U.S. Naval War College;

Mackubin Owens, U.S. Naval War College; Steve

Rosen, Harvard University;

Gary Schmitt, Project for the New American

Century;

Abram Shulsky, The RAND Corporation;

Michael Vickers, Center for Strategic and

Budgetary Assessment;

Barry Watts, Northrop Grumman Corporation;

Paul Wolfowitz, Nitze

School of Advanced International Studies, Johns

Hopkins University;

Dov Zakheim, System Planning

Corporation.

The above list

of individuals participated in at least one

project meeting or contributed a paper for

discussion. The report is a product solely of

the Project for the New American Century and

does not necessarily represent the views of the

project participants or their affiliated

institutions.

|