An edited

extract from Robert Caldwell: A scholar-missionary in

colonial South India by Y. Vincent Kumaradoss (ISPCK,

2007). www.ispck.org.in

An edited

extract from Robert Caldwell: A scholar-missionary in

colonial South India by Y. Vincent Kumaradoss (ISPCK,

2007). www.ispck.org.in

Church Times, 26 October 2007

Robert Caldwell was revered by his

people - but a victim of party spirit, Vincent

Kumaradoss says in a new biography.

Caldwell was soon beset with a series of

problems that began to hamper his work. His tenure as

Bishop was the most trying period of his time in

Tirunelveli. It was tragic that so outstanding a career as

Caldwell's should have been blighted at the end by his

rupture with the Society for the Propagation of the

Gospel's (SPG's) Madras Diocesan Committee (MDC).

Feeling his age, he was not physically the

same person he had been, and he complained of his health

often. The theme of weariness began to recur constantly in

his correspondence. He was now, despite this, a man in a

hurry. Even though he had not been keeping good health, and

a hostile campaign was launched against him and his wife,

Eliza, he was driven by his sense of duty. The routine

continued, in spite of illness, and in spite of setbacks

and disappointments. The missionary task of evangelism

proceeded as Caldwell stood his ground.

It is difficult to avoid the impression

that the conflict arose to a considerable extent because

the MDC seemed deliberately to assert itself in order to

provoke and frustrate the new Assistant Bishop. A careful

reading of the records makes it almost impossible to argue

that Caldwell was not the entirely innocent victim of

almost unrelieved malice on the part of the MDC throughout

his episcopate.

Gratefully remembered: a bronze statue of

Bishop Caldwell erected in 1968 on the Marina beach,

Chennai. There it is one of eight statues of distinguished

Tamil scholars commissioned by the organisation Dravida

Munnetra Kazhagam. Caldwell is described as "the pioneer

Dravadian linguist" His own occasional references to

"party" indicate the main source of this, and that his

opponents brought to the issues between him and them the

often virulent internal disputes of the Church of England

in England at that time. This was something that the SPG's

foundation documents, back at the beginning of the 18th

century, had required its members to eschew, and at its

best successfully. But the Society and its members were not

always at their best, the later decades of the 19th century

being a case in point. 'The bier was met by a crowd with

"all the marks of loyalty and love" '

The reason for the antipathy shown to him

by the MDC in his last years, by comparison with earlier

times, is difficult to assess. Much of it must be due to

the calibre and experience of the men who by chance then

composed the committee, and the influence of their

secretary. Clearly, there was between them a lack of

understanding of the situation of SPG missionaries and the

native Church far away in the field.

To add to these shortcomings, there may

have been some jealousy over Caldwell's high reputation and

influence in England, and the financial support he

attracted direct from there, much of it going into Eliza's

schools.

Tension on ideological grounds had been exacerbated after

Caldwell was appointed Assistant Bishop, as the MDC was

coming to be dominated by people sympathetic to the Oxford

Movement. When they learned that Caldwell was, as they saw

it, an Evangelical, they began to look down on him.

He decided on a course to put the MDC in

its place. His immediate task was to restore his prestige

and inspire respect for the sacred office of bishop. Faced

with a chain of unpleasant events, the struggle was to

consume much of his time.

Gothic in India: the newly refurbished bungalow for the

pastor and its attached chapel at Idaiyangudi today - an

enhancement of the single room, 17 by 11 feet, that

Caldwell occupied on his arrival in 1841

Caldwell felt strongly the need to discontinue the MDC's

connection with the mission. While making his appeal in

England at this time, and expressing his hope of returning

to Tirunelveli with a fresh mandate in a fresh atmosphere,

he seized the opportunity to add a personal, almost

pleading note on his declining health:

"Though my health is only partially

restored, I should be delighted to return again to a field

of labour I love so well, if I could do so with advantage.

It would give me the greatest possible pleasure to devote

the last days of my life to the work of reorganising the

Tinnevelly Church and Mission on the lines I have

indicated, with the Society's approval; but I hope I may,

without impropriety, be permitted to say that, at my

advanced period of my life, with my nervous and sensitive

constitution, I should not feel myself justified in

returning to India to be placed in the same trying position

as before, and to encounter again those troubles and

worries which brought on the illness from which I have

suffered for the last two or three years."

In response to his suggestion, a resolution

was passed by the standing committee on 14 February 1884,

which ran as follows: "Agreed that the Bishop of Madras and

the Madras Diocesan Committee be requested to favour the

Standing Committee with an expression of their opinion upon

Bishop Caldwell's statement: it being prima facie the

opinion of the Standing Committee that there are no

insurmountable objections to the separate administration of

the Diocese of Tinnevelly." The committee in Madras,

however, took a different view.

In its detailed minute of 30 May 1884, the

MDC concluded that Caldwell's proposal was inexpedient and

impractical at that time. That only 12 years later, in

1896, it was possible for Tirunelveli to become, by

contemporary standards, a properly constituted Anglican

diocese is a measure of the reactionary, negative, and

misguided character of the opposition Caldwell faced, and a

measure, too, of the soundness of his own vision and

aspirations.

THE MDC was desperate to stall anything that would diminish

its domination. A long list of "animadversions" against

Caldwell was addressed to the SPG in London. The whole

exercise was clearly designed to present Caldwell as the

disrupter of peace in Tirunelveli, and to discredit him in

the eyes of the SPG in England, where, in fact, he was

respected and had considerable influence.

The MDC pursued its game with undiminished

vigour, intent now on crippling the progress of Caldwell

College. Pleading financial constraints, they drastically

cut the grant to the college.

In order finally to snuff out the college's

existence, three reasons were advanced. First and foremost

was that the SPG could not afford to maintain the college

due to its own financial crisis. Second, the results of

examinations were unsatisfactory. Third, the number of

students who attended the college was small.

Whatever might have been the truth behind these claims, it

was clear that the MDC was unwilling to see the institution

survive. The MDC closed the college section in 1894 and

reduced it to the level of a high school.

THE MDC had already characterised Eliza as

having an undue influence over the decisions of the ailing

Caldwell. Given its hostility towards Eliza, the MDC now

turned its attention to her pet project, the Girls Normal

School at Tuticorin, where a "large, beautiful and

substantial building", erected over two full years,

"through the indefatigable exertions" of Bishop Caldwell

and Eliza, had been opened by the Metropolitan of

India.

The School came under the scrutiny of the

committee when, in order to reduce its long-term financial

commitments, the MDC refused to take any responsibility for

new schools that had not been sanctioned by it. The MDC

questioned the legitimacy of this "Female Training

College", as the sanction of the committee had not been

sought.

According to the MDC, this was done in

contravention of the rules of the SPG, and it wrote to

Caldwell asking for an explanation. Caldwell argued that

they had not ignored the rules of the SPG, as the school in

question was not a new institution at all - it was, in

fact, merely the "Tinnevelly portion" of the "S.P.G. Female

Normal School" established in Trichy by his daughter

Isabella Wyatt, and now transferred to Tuticorin.

This step was taken because of the

practical difficulty involved in sending the girls to

Trichy. The MDC, bent upon frustrating Caldwell and Eliza's

efforts, passed a resolution that it was unable to

recognise the institution or undertake its future

expenditure.

The resolution came as a rude shock to

Eliza. Surprised and upset, she retorted that "it was quite

gratuitous on their part to pass such an unfeeling and

uncalled for Resolution." For Eliza, it was an insult

heaped on her for "life-long voluntary labours of forty

three years in the cause of female education", and a

deliberate measure intended to subvert the "crowning

effort" of her educational career.

The secretary of the MDC simply reiterated

the committee's stand that it was not possible to accept

responsibility for the school at Tuticorin. He argued that

a large sum of money from home was entrusted to the MDC

chiefly for the extension of "Christ's Church", and was

"only partially indeed to be spent in old Missions and in

the training and helping forward in life of the children

and grandchildren of Christians".

Eliza issued an appeal for money to

establish more girls' schools, and a female training

college for teachers, at Tuticorin. The appeal contained a

history of her 44 years of work in Tirunelveli in the cause

of female education.

Despite her attempts to get grants to keep

the institution going, the school had to give up the

training section in 1893. In 1894, however, after her

husband's death, while the training institution was shifted

to Nazareth, the school was upgraded as a high school.

AFTER 1888, Caldwell's "powers were slowly

ebbing out". Yearning for a cooler climate, he frequented

Kodaikanal, which was congenial to his health. He began to

spend much of his time there, and managed the affairs of

his office, shuttling between Kodaikanal and Tuticorin. He

began to suffer from physical exhaustion.

In July 1890, he requested the Bishop of

Madras to relieve him of miscellaneous work connected with

his district, so that he could continue purely with the

episcopal part of his work, such as confirmations and

ordinations.

Seeking a retirement allowance, Caldwell

wrote: "In taking this step, however, I feel under the

necessity of stating that I can only do so on the condition

that the Society will continue to [pay] me my present

stipend for the remaining years of my life. In my old age I

naturally require comfort and attention which as a younger

man I could dispense with."

The standing committee took strong

exception, and pronounced its displeasure over his seeking

to fix his retirement allowance as a "condition", and

disallowed his pension claim. The Bishop of Madras

solicited Tucker, the secretary of the SPG in London, for

release of pension as per Caldwell's wish. The SPG finally

released the pension on his terms in January 1891.

During his last visit to Tuticorin in

January 1891, he wrote a letter to Bishop Gell, resigning

his office from 31 January 1891. The very next day, along

with his family, he embarked on his last journey to

Kodaikanal.

THE STRAIN of a continuously busy life, the

hot climate of Tirunelveli, and the prolonged and

persistent attempt to derail his initiatives during the

later period of his bishopric had exacted a toll upon

Caldwell's frail body. In feeble health and beyond

recuperation, he spent the next seven months at Roslyn, his

bungalow in Kodaikanal, a hill station in the Nilgiris.

On Wednesday 19 August 1891, while

returning from his usual walk, he contracted a chill. The

following day, medical attention was sought. He was

confined to his room, where, undisturbed, he pulled through

for the next three days.

On Monday, he took a short stroll with

Eliza, but in the evening he was seized with fever. He

slowly slipped into a coma on the Thursday night. Though he

revived on seeing his son, Dr Addington Caldwell, who came

to see him from Australia, his condition was fast

deteriorating. He slowly slipped into a coma on the

Thursday night.

Next morning, at 9 a.m. on 28 August 1891,

Eliza and his children watched as Caldwell entered into

eternal rest at the age of 77.

The coffin carrying his body, dressed in

his episcopal robes, was conveyed down from the hills, a

journey of some 200 miles, by way of Palayamkottai, to

Idaiyangudi, to be with the people among whom he had

laboured for half a century. At Palayamkottai, a solemn and

impressive service was held on the Sunday, honoured by the

presence of "a large crowd of natives" and several

missionaries and Indian clergy.

The final journey from Palayamkottai

culminated on Tuesday morning, 1 September 1891, at 7 a.m

at Idaiyangudi, where the bier was met by a large crowd

with "all the marks of loyalty and love". After the funeral

service, the mortal remains of Robert Caldwell found an

appropriate resting-place below the altar of Holy Trinity,

the church that had been built by his own exertions, and

consecrated by him.

Heart-rending sobs and praise filled the

air as crowds of Christians, Hindus, and Muslims thronged

to have a last glimpse of the revered face, and to pay

their last homage to the priest and bishop who had for so

long been their "father and friend".

As his body came to rest in the mother

church of Tirunelveli, in many ways one of Bishop Robert

Caldwell's cherished desires had perhaps been fulfilled.

During his last visit to England in 1883, his parting words

at a special service held in the SPG's chapel, just before

his return to India, had been: "For Tinnevelly I have

lived, and for Tinnevelly I am prepared to die."

The Caldwell saga remained to be assessed

and justly honoured.

|

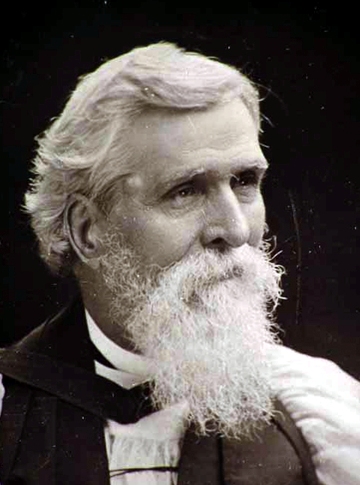

Bishop Robert Caldwell (1814

-1891) was an orientalist who pioneered the study

of the Dravidian languages with his influential

work Comparative Grammar of Dravidian Languages

(1856; revised edition 1875). Robert Caldwell was

born on May 7,1814 to Scottish parents. Initially

self-taught and deeply religious, young Caldwell

graduated from the university of Glasgow and was

fascinated by the comparative study of languages.

At 24, Caldwell arrived in Madras on January 8,

1838 as a missionary of the London Missionary

Society and later joined the Society for the

Propagation of the Gospel Mission (SPG). Caldwell

realised that he had to be proficient in Tamil to

preach to the masses and he began a systematic

study of the language.

Bishop Robert Caldwell (1814

-1891) was an orientalist who pioneered the study

of the Dravidian languages with his influential

work Comparative Grammar of Dravidian Languages

(1856; revised edition 1875). Robert Caldwell was

born on May 7,1814 to Scottish parents. Initially

self-taught and deeply religious, young Caldwell

graduated from the university of Glasgow and was

fascinated by the comparative study of languages.

At 24, Caldwell arrived in Madras on January 8,

1838 as a missionary of the London Missionary

Society and later joined the Society for the

Propagation of the Gospel Mission (SPG). Caldwell

realised that he had to be proficient in Tamil to

preach to the masses and he began a systematic

study of the language.