On

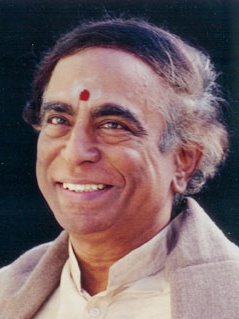

17th September, 2000, Lalgudi turned 70 - an event worthy of celebration.

Very few are blessed with a fruitful life in which one gives much more to

the world than one takes from it. Fewer still are those who are associated

with a noble art and an illustrious career, like Lalgudi. He can look back

upon decades of triumph, glory and achievements, with pride and

satisfaction. My association with him covers more than half of his 70 years

and when I too look back with him, I recollect a remarkable event that

occurred about 23 years ago.

On

17th September, 2000, Lalgudi turned 70 - an event worthy of celebration.

Very few are blessed with a fruitful life in which one gives much more to

the world than one takes from it. Fewer still are those who are associated

with a noble art and an illustrious career, like Lalgudi. He can look back

upon decades of triumph, glory and achievements, with pride and

satisfaction. My association with him covers more than half of his 70 years

and when I too look back with him, I recollect a remarkable event that

occurred about 23 years ago.

A large audience sat spell bound under the soothing shower

of melody from Lalgudi's violin in his solo concert at Anushakti Nagar in

Bombay. One rasika was so overwhelmed by the moving quality of the music

that he approached the dais with calm and steady steps, tossed a gold chain

on to the lap of the artist and, as calmly as he came, walked away, before

anyone could grasp what had happened. There was no semblance of an impulsive

or theatrical behaviour in what he did. On the contrary, it looked like a

deliberate and spontaneous tribute to Lalgudi's music.

In fact, it was one of those performances of Lalgudi which

transport the discerning music lover to a blissful state where anything

mundane seems trivial. It is not an attribute ordinarily acquirable by mere

training, duration of practice, a rich collection of songs or mastery over

the instrument or voice. It has much to do with the attitude towards music,

awareness of its origin and understanding of its character and purpose. Like

all arts in India, Carnatic Music has a spiritual origin, with its roots in

"Bhakti". It has been nurtured and assiduously developed by saintly

composers like Purandaradas, Ramadas, Thyagaraja, Dikshitar, Syama

Sastry, Jayadeva, Kshetragna and others. Lalgudi's understanding and

appreciation of this truth is deeper and far more intense than those of most

of contemporaries. In this particular aspect he belongs to the class of

Papanasam Sivan and Mysore Vasudevachar.

Also, this understanding is truthfully reflected in his

performances, in every note emanating from his violin, in every raagam,

kriti or even in swaraprastharam. This is his distinction, his virtue that

distinguishes him from most of the other musicians, who set store by the

mere mastery of the science and grammar of music and consequently revel in

the exhibition of virtuosity, bereft of spirit.

The spiritual approach to Carnatic Music was inculcated in

Lalgudi from his childhood, by his father and "Guru" Shri V. R. Gopala Iyer.

Shri Gopala Iyer was a pious person, simple, humble and free from the

worldly wiles and guiles. His mind was filled only with music and divine

thoughts, always alert and active. Those who learnt music at his feet tell

us how much he emphasised and enforced discipline and a sense of dedication

while teaching. Music, for him, was not just like science, geography or

arithmetic, to be learnt with academic interest or for scoring marks. Music

was "Saadhanaa" in his view and he would insist on every student always

remaining conscious of its spiritual link. This concept forms the bedrock of

"Lalgudi School" even now.

Shri Jayaraman made his entry into the world of Carnatic

Music Concerts, when he was just 12. He set out with his bow and violin,

armed with the knowledge, skill and understanding imparted to him by his

father. There was no patron like "Viswamitra" for Lord Rama, to escort him

into the world which was then dominated by a galaxy of musicians like

Ariyakudi, Mahjarajapuram, Semmangudi, GNB, Alathur Brothers, Chowdiah,

Rajamanickam Pillai, Palghat Mani Iyer, Palani Subramania Pillai, to name a

few.

Like Lord Rama, he lost no time in giving proof of his

profound talent, undaunted by the formidable reputation of the stalwarts

whom he accompanied on the concert platform. Apart from his sincerity and

adaptability, what singled him out as a peerless accompanist was the ready

responses he gave to the best efforts of the main artist in Aalapanaa,

Neraval or Swaraprasthaaram, with matching sparkle and imagination.

Every musician realised that having Lalgudi as the

accompanist would surely elevate the quality of his concert to heights

otherwise not easily possible to reach. Though, for reasons not difficult to

guess, none of them would come out with an open acknowledgement, in those

days. No "laya" based exercise, however intricate or complex it might be,

was beyond his grasp. Alathur Brothers, whose exceptional prowess in the

"laya" aspect was well known, would prepare a Pallavi, replete with compelx

rhythmic calculations, in uncommon "Thaalams", practice and rehearse

thoroughly and delight the knowledgeable audience by presenting it in the

concert with characteristic gusto. With any other violinist accompanying

them, they would just pass over to the next item. But with Lalgudi by their

side, they would make a subtle challenge to him to play that Pallavi, with

the anuloma or prathiloma they had so deftly performed. An astounded

audience and exultant Alathur Brothers, would watch Lalgudi playing that

Pallavi back, impromptu, with precision and equal gusto. This was a feast

performed regularly, only by Lalgudi and none else.

His emergence, as a soloist exclusively, marks the second

phase of his career, in which he found unlimited freedom to give expression

to his illimitable imagination. His solo concerts regaled large audience not

only in this country but in UK, US, Canada, Middle East, Malaysia and

Singapore as well, notwithstanding the fact that he never resorted to

populist techniques or puerile innovations like clothing Carnatic Music in

the garb of Hindusthani Music. Not once has he indulged in the common place

over emphasis on rhythm to build up a noisy climax, for gratifying the

gallery. Playing to the gallery has always been anathema to him. He has

never digressed into a vulgar display of virtuosity, though he is second to

none in his mastery of rhythm or mastery of the instrument.

His forte is in using his mature aesthetic sensitivity to

build an edifice of any raagam he chooses, like a sculptor chiselling a

statue of exceptional beauty - bring out its splendour in all its facets,

render the kriti with appropriate sangathi's to highlight the "bhaavam" or

mood inherent in it and to make swaraprasthaaram a veritable feast by

weaving patterns of amazing symmetry that merge with the selected phrase of

the kriti with unobtrusive effort but conspicuous effect. Mere virtuosity

and command over "laya" are purposefully subordinated to the principal

objective of integrating sruthi, layam, rasa and bhaavam into one

homogeneous and delectable treat that showers on the audience a blissful joy

different from the sensuous and earthly kind - His imagination, his bow, his

fingers and his violin, in unison produce that kind and quality of music

which the genius Saint Thyagaraja envisaged. when he sang "Svaadu phalaprada

Sapta swara raga Nichayasahitha Naadaloludai Brahmananda mandave"

What he cherishes in his mind for the art of music is a

feeling akin to "Bhakti", that keeps urging him to give creative expression

to the surging waves of imagination within. It did not permit him to rest

content with being a performing violinist and ushered him into the third

phase of his career in which his creative genius was activated and directed

towards composing Varnams, Tillanas and songs for dance drama and opera.

Tillanas in Tilang and Desh appeared in the early

seventies. Renowned dancers like, Kanaka, Kamala, Alarmel Valli, Chitra

Visweswaran and others choreographed dances for his compositions. Varnams in

Nalinakaanti, Asaveri and Bowli followed, all of them with a perceptible

qualitative difference from the varnams and tillanas by other composers,

thereby representing an advance in concept, structure and tempo. Behag and

Kaapi Tillanas in Tisra Nadai, Revathi, Yamuna Kalyani and Pahad Tillanas in

misrachaapu and Tillanas in unusual raagams like Vasanti, Karna Ranjani, in

Hindusthani raagams like Madhuvanti, Raageshri and Baageshri constitute an

amazingly rich variety of magnificent pieces that could dawn in the mind

only of a gifted musician who has truly imbibed "Raagasudhaa rasa Paanam",

over a period of half a century.

The innovative aspect in all these Tillanas in the creation

of an outline in the Pallavi and Charanam to provide scope for filling in

with innumerable variety of swara phrases. Tillanaas in Sindhubhairavi,

Maand, Hamsaanandi are brilliant examples of this feature. The commonly held

belief that "tradition" and "innovation" or "creativity" do not go together

has been disproved by Lalgudi by demonstrating that adherence to tradition

is not opposed to or an impediment to achieve creative excellence, and that

there is no paradox in remaining faithful to tradition and being creative as

well.

Excelling all these accomplishments, what can be rightly considered as of

monumental stature is the musical score by Lalgudi for the dance drama "Jaya

Jaya Devi". The lyrics and tunes are so much in harmony as to bring out the

rasaa and bhaavam with telling clarity, lending an unbelievable degree of

realism to the scenes. The elegant words and phrases in the lyrics and the

descriptive and narrative passages offer abundant scope for abhinayam and

the setting in different Thaalams and Nadai, for Nrityam. The depth of his

involvement with the theme, the context, and the moods vivified in the drama

is evident in the choice of the raagam, the form of composition and the pace

of rendering; the whole creation is a choreographer's delight. By all

standards this achievement of Lalgudi is extraordinary, unequalled and

invaluable. It is a work, a masterpiece that brings to mind Naukacharitram

of Thyagaraja; Raamanaataka Kirtanas of Arunachala Kavi and Nandanaar

Charithram by Gopalakrishna Bharathi.

Lalgudi stands alone at a height well above the rest in the

quality of his music, the quality of his creations and the quality of his

contribution to the wealth and growth of Carnatic Music.

In the greatness conferred on him by the astonishing

versatility he has displayed, he stands alone not only in the

contemporaneous scene but also in the wide span of the entire 20th century.

His contribution will certainly be recorded in golden letters when the

history of evolution of Carnatic Music is written. May God bless him with

good health, active mind, an intellect of undiminishing sharpness and long

life.