|

TAMIL NATION

LIBRARY: Caste & Tamil Nation

[see also 1.

Sri Lanka Tamils - Ethnonyms: Tamils, Tamilarkal ("Tamil people")

- Professor Brian Pfaffenberger

2.Caste

& the Tamil Nation - Brahmins, Non Brahmins & Dalits

3.

Fourth World Colonialism, Indigenous Minorities and Tamil Separatism in

Sri Lanka, in Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars by Bryan

Pfaffenberger. 8 pgs.]

From the Preface

From the Preface

From the Introduction

From the Introduction

"...The caste system of South India,

epitomized (as are most things South Indian) by the social formation of the

Tamil-speaking lands is if anything even more rigid and redolent of the

hierarchical ethos than that of North India. And yet - here, of course, is

the uniquitous paradox with which South Indian presents us - the Tamil caste

system comprises features which are not only unknown in North India but are

also without any clear foundation in the Sastric lore. So divergent is the

southern system that one is tempted to say, with Raghavan (n.d.:117), that

the Sastras have "little application" to the Tamil caste system, which

should be analyzed in purely Dravidian terms...But to do so is to forget the

fundamental challenge with which Dravidian culture presents us, namely, to

see it as a regional variant of the Gangetic tradition of Hinduism. We are

obliged to observe, for instance, that the highest and lowest ranks of the

Tamil caste hierarchy - that of the Brahman and of the scavenging Paraiyar

Untouchables -are perfectly explicable in Sastric terms. ..

To argue that the Sastric ranking ideology has "little application" to

the Tamil caste system is to ignore the challenge that South India presents

to ethnology. Yet it is also true that, in the middle ranges of the Tamil

caste hierarchy, the ranking categories and overall form of the Gangetic

caste tradition are very poorly reproduced.

The most striking aspect of this anomaly - the one with

which this monograph is chiefly concerned - is the enigmatic status of

certain non-Brahman cultivating castes, which are traditionally of the Sudra

(or Servant) rank in Sastric terms and which are epitomized by the

cultivating Vellalars of the Tamil hinterland. Throughout South India, in

those areas in which Brahmans are not the chief landowners, Sudra

cultivating castes often possess what Srinivas has termed "decisive

dominance""

From

the Preface From

the Preface

The pages to follow recount an attempt to comprehend the

traditional caste system of the Tamil

lands of South Asia in terms of the religious beliefs and world view of

Tamil culture, which is without doubt one of the most distinctive of Hindu

civilization's variant regional traditions.

This study focuses, in particular, on the high dominant

cultivating castes of the Sudra (Servant) status in regional Hindu ranking

terms, and seeks to explain why it is that among Tamil folk and Dravidians

generally, such castes rank far higher than they would if caste statuses were

judged solely in terms traditional, textual criteria of rank.

|

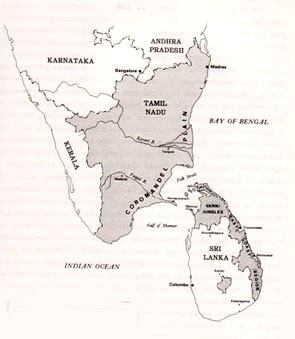

Tamil Speaking Lands of India &

Sri Lanka

- shaded areas

|

Rooted in a study of ritual among the Sudra agriculturalists of

Sri Lanka's Jaffna Peninsula this monograph seeks to reveal a quintessentially

Tamil recasting of the classical Hindu tradition of ranking and, what is more,

to uncover the distinctively Dravidian view of the universe in which the

puzzling caste statuses of the traditional Tamil caste system were constitued

with meaning and legitimacy.

Whatever negative value we may assign to the caste relations

that they legitimate, it is none the less true, as I hope to show, that the

religious foundations of Sudra domination constitute one of the most creative

and architectonic achievements of the world's traditional cultures. This study

is intended to contribute to our emerging awareness of the distinctive genius of

Tamil civilization.

That we have thus far failed to recognize the distinctive

regional character of Tamil culture has much to do, I believe, with ahistoricism

of much modern anthropology. Tamil culture arose in a complex historical process

by which the civilization of the Gangetic plains diffused to the South.

We are little encouraged to apprehend its nature by refusing to

consider how modern Tamil culture is in certain respects a product of that

process. Of course, much nonsense has written about the history of the Tamils,

not a little of it being colored by the anti-Brahman and Tamil separatist

movements of this century.

Much of what has been written about Tamil history is well

described in the terms

Radcliffe-Brown would have used for it: pseudo-historical speculation. But

Radcliffe-Brown admonished us to abandon history, not because there was anything

wrong with history as such (indeed, he believed that it was only through

historical analysis that one could explain the appearance of particular social

forms in particular places), but rather because the type of societies normally

studied by anthropologists lacks the records which would make history possible.

The history of Tamil culture is indeed possible, as Stein (1980) has shown, for

there are abundant historical sources-- such as the many - thousands of temple

inscriptions--that offer a foundation for historical interpretation.

My interpretation of caste in Tamil culture is founded squarely

on the premise that our understanding of the meaning of caste statuses in the

Tamil tradition --an understanding that has thus far eluded scholarship --

emerged only when Tamil culture is understood both anthropologically and

historically. On grounds both of training and temperament, _ feel much more

comfortable with the anthropological approach than I do with the historical, and

on that account I have simply appropriated the fine historical interpretations

which have been offered by Stein (1980) and Ludden (1978). Even so, these

understandings have been subjected to an essentially anthropological

methodology, one recently employed by Geertz (1980) and well outlined by Dumont:

What is known of the past, on the plane of genera and more

or less, preliminary information, is useful to the anthropologist . . .

[but] the present has an advantage over the past.. . . The intensive study

of the present by the anthropologist, because it is complete by definition .

. . is incomparable for bringing to light relations, configurations, or

structures in the social datum, in contrast to historical data, always

fragmentary. Once such a configuration is isolated in the present . . . one

may hope to find something of it in the past, and to use it to put in an

intelligible order what often appears in the hands of classical indology . .

, as a purely accidental collection (1980:xxv).

The first two chapters below attempt to isolate the

configuration with which I am concerned, namely the high status and privileges

of Sudras in Tamil culture, both in light of the ethnology of South India

(chapter one) and my own studies in Sri Lanka's Jaffna Peninsula (chapter two).

There follows an interpretation of the historical process by which Tamil culture

arose, one that I believe sheds light on certain quintessentially South Indian

institutions--such as the distinction between right- and left-hand castes--that

have not been satisfactorily explained in historical terms alone. In so doing I

have modified very slightly the interpretations of the South Indian social

formation offered by Stein and Ludden, but only very slightly, and, it is to be

hoped, with profit.

The research on which this monograph is based was conducted in

Sri Lanka during 1973 and 1974-75 with the kind assistance of the Institute for

International Studies, University of California, Berkeley; that university's

Department of Anthropology; and a Foreign Area Fellowship of the Social Science

Research Council and the American Council of ' Learned Societies. A fellowship

from the National Endowment for the Humanities permitted me to situate my Sri

Lanka evidence in the wider context of the literature on Tamil India, and

provided a year of release time from my teaching duties.

From the

Introduction...

"The pages to follow recount an attempt to comprehend one of the most

enigmatic aspects of the South Indian tradition, its caste system.

The caste system of South India, epitomized (as are most things South

Indian) by the social formation of the Tamil-speaking lands is if anything

even more rigid and redolent of the hierarchical ethos than that of North

India. And yet - here, of course, is the uniquitous paradox with which South

Indian presents us - the Tamil caste system comprises features which are not

only unknown in North India but are also without any clear foundation in the

Sastric lore. So divergent is the southern system that one is tempted to

say, with Raghavan (n.d.:117), that the Sastras have "little application" to

the Tamil caste system, which should be analyzed in purely Dravidian terms.

But to do so is to forget the fundamental challenge with which Dravidian

culture presents us, namely, to see it as a regional variant of the Gangetic

tradition of Hinduism. We are obliged to observe, for instance, that the

highest and lowest ranks of the Tamil caste hierarchy - that of the Brahman

and of the scavenging Paraiyar Untouchables -are perfectly explicable in

Sastric terms.

The traditional South Indian Brahman - learned, of high Gangetic

ancestry, and orthodox in his observance of the manifold rules of personal

and caste purity - well illustrates the combination of lifestyle attributes

that Hindus, throughout time, have rewarded by conferring on Brahmans the

highest standing among men.

The South Indian Brahman indeed exemplifies purity, which is a state of

sanctity brought about by distancing the self (and the caste) from the

tainting, debilitating processes of life and death. And the lowly Paraiyar

-unlettered, of no dignified lineage, and saturated with the pollution that

comes of handling the carcasses of cattle -equally well exemplifies tne

opprobrious features that, in the ancient texts as well as among Hindus

today, condemn a caste to a despised status.

To argue that the Sastric ranking ideology has "little application" to

the Tamil caste system is to ignore the challenge that South India presents

to ethnology. Yet it is also true that, in the middle ranges of the Tamil

caste hierarchy, the ranking categories and overall form of the Gangetic

caste tradition are very poorly reproduced.

The most striking aspect of this anomaly - the one with which this

monograph is chiefly concerned - is the enigmatic status of certain

non-Brahman cultivating castes, which are traditionally of the Sudra (or

Servant) rank in Sastric terms and which are epitomized by the cultivating

Vellalars of the Tamil hinterland. Throughout South India, in those areas in

which Brahmans are not the chief landowners, Sudra cultivating castes often

possess what Srinivas has termed "decisive dominance" (1959).

Numerically predominant in an area and endowed with the lion's share of

the land, the dominant caste believes itself to be entitled to rule the

villages in which it resides, and does not snrink from the use of force to

maintain what it sees as its legitimate privileges (Mandelbaum 1970:II,

358ff).

Judged in purely Sastric terms, the non-Brahman dominant caste of South

India - a caste which possesses only the lowly Sudra rank in the Sastric

tradition of caste categories (varnas)- should not merit a very high caste

rank. Yet, proclaiming themselves to be very pure and respectable indeed,

Vellalars, for instance, are judged to stand in public esteem just below the

Brahmans.

That Vellalars are so acknowledged, is actually quite mysterious, for

Vellalar castes, at the same time that they proclaim their great purity, in

fact tend to lead a fairly impure lifestyle. Vellalars, for instance, do not

eat beef, but they very often eat other kinds of meat; drink alcohol; carry

on close relations with impure, Untouchable laborers; supervise blood

sacrifices; drink the blood of sacrificial victims; remarry widows; and, in

general, throw themselves lustily into the tainting affairs of day-to-day

life.

These practices are very much out of keeping with the other-worldly,

ascetic-like customs of the pure castes, and according to the classical

doctrine, the Vellalars' rank should be low indeed. Yet Vellalars,

throughout tile Tamil lands, are ranked very high..Furthermore, they are

ranked higher in public esteem than certain non-Brahman castes that emulate

the Brahmanical ideal of purity, a situation that, for Dumont (1981:88),

indicates that the classical ranking ideal is "in abeyance."

The contradiction between Vellalar claims to purity and the realities of

their worldly lifestyle emerges clearly, according to

Beck, in the symbolism of plowing. Brahmans, since the most ancient

times, have disdained the plow, believing that "plowing land is a polluting

activity since overturning the soil threatens the life within it." Brahmans

hire non-Brahman laborers to do their plowing for them. Yet Vellalars esteem

the act and advertise their association with it, as if to flaunt Brahmanical

ideals and drive home tauntingly the idea that they possess a high rank that

they do not deserve (Beck 1970:782-83, n. 12).

When measured against the ranking paradigm of the Dharmasastras, the

status of Vellalars appears to be both irreligious and artificially

inflated. The Dharmasastras outline the Hindu notions of an interdependent,

caste-based social order, in which the greatest merit (both social and

religious) attaches to those who adhere to their ascribed status. These

notions, collectively known as the varnasrama dharma ("duties of the four

caste categories and four stages of life [asrama]"), reflect the most

essential theme of Indian social thought: as in Plato's Republic, there is

outlined, for each man, "a place in society and a function to fulfill, with

its own rights and duties" (Basham 1954: 138).

Dumont terms the spirit of the varnasrama dharma "holistic": "the

stress," he asserts, "is placed on society as a whole, as collective Man;

the ideal derives from the organization of society with respect to its

[religious] ends (and not with respect to individual happiness); it is above

all a matter of order, of hierarchy; each particular man in his place must

contribute to the global order, and justice consists in ensuring that the

proportions between social functions are adapted to the whole" (1981:9).

That Vellalars claim a rank higher than the one they deserve seems to

flaunt the very essence of the Sastric social ideal, as it was expressed in

the Laws of Manu: "it is better to do one's own duty [svadharma, the

ascribed occupation and duty of a caste] badly than another's well" (cited

in Basham 1954:13).

The duty of Sudras, according to the Dharmasastras, is to serve the

higher caste-categories (varnas) with humility. The three higher varnas,

Brahman (priests and scholars), Ksatriyas (warriors and rulers), and Vaisyas

(commoners), were collectively known as the twice-born (dvija), due to their

ritual rebirth in the orthodox Vedic initiation rites.

As the purest and, from a religious standpoint, the most powerful of men,

Brahmans were deemed to have dominion over all others. In practice, however,

the religious duties of Brahmans - studying and teaching the Vedas - were

considered sufficiently challenging to warrant for them not wordly dominion,

but rather a life of "plain living and high thinking" (Kane 1974:110).

The practice of worldly dominion (war and government) was therefore

left-at least in classical theory-to Ksatriyas, with the understanding that

even the most powerful Ksatriya king was still subordinate in status to

Brahmans. To Vaisyas was left the day-to-day business of life. Below them

all, and despised for their impurity (asauca),were the lowly Sudras.

In the Sastras (Lingat 1973; Kane 1974) Sudras were likened to burial

grounds, which are among the most impure of places. They were forbidden to

study the Veda, to consecrate sacred fires, to carry on certain life-cycle

ceremonies (samskara, including the crucial initiation rite), to give gifts

to Brahmans save under great restrictions, to claim a short pollution period

after a kinsman's death, to give food to Brahmans, to come close to

Brahmans, to perform ascetic acts, or to claim prestige.

They were enjoined to esteem their poverty, for the wealth of Sudras was

held to be a vexation to Brahmans. So far from seeking riches, they were

admonished to serve the higher varnas with humility. The status of Sudras in

the Sastras, in sum, was depicted as a very lowly one, although, to be sure,

there was an even lower status, that of the candalas or Untouchables.

Nonetheless, it is quite clear that the classical tradition mandates a life

of poverty and service for Sudras, and it is equally clear that the

scriptural mandate is regularly contravened in practice by the Sudra

dominant castes of the South.

So distant is the varna scheme from actual social reality that many

scholars discount its relevance or utility for the analysis of caste

anywhere in the South Asian culture area. Yet to do so is to ignore the fact

that Hindus themselves view the Sastras as the fons et origo of their social

design.

Whether or not the Sastric scheme applies exactly to the actual form of

caste ranking, Hindus all over South Asia - including the Dravidian South -

use the language and the ideology of those scriptures to conceptualize their

social relations. Furthermore, it is quite clear that the North Indian caste

system, at least, conforms in principle to the overarching design of the

texts. Positions of respectability, of domination, of wealth, and of

landholding are held almost universally in North India by persons who claim,

and are thought by others, to possess the twice-born status (see, for

instance, Gould 1964:35). It is believed in North Indian villages that the

twice-born, who are scrupulous in their maintenance of domestic purity and

orthodox customs, possess the right to dominate others because of their

religious merit (acquired in a former life) and because of their purity

(Wadley 1976).

The Sudra dominant caste of the South clearly does not possess the

Sastric entitlement to dominate other castes. Nonetheless, Vellalars, for

instance, believe themselves to possess the right to claim the honor,

respect, and services of a wide variety of non-Brahman subordinate castes.

Among them are professional castes-potters, watchmen, carpenters, and many

more - whose statuses, if lower than that of Vellalars, are nonetheless

fairly respectable. (Certain professional castes whose duties involve the

routine handling of impurities, such as tonsure or the washing of menstrual

cloths, rank much lower, at or below the line which separates the touchable

from the untouchable castes.)

As much as thirty percent of the population belongs, not to these

respectable professional castes, but rather to very low ranking and

impoverished castes called Untouchables (or, with polite circumlocution,

"Original Dravidians" [ati tiravita] ; alternatively, "children of God"

[harijans]).

So low and despised are these castes, which are epitomized by the Pallar

and the Paraiyar of the Tamil lands, that people of respectable caste rank

believe their touch to be defiling. For centuries, lowly Untouchables (the

retainers of Vellalar masters) have performed the backbreaking

labor-weeding, transplanting, harvesting-that has helped to bring luxuriant

harvests to the rice paddies and gardens owned by the high caste folk (Beck

1972, 1976; Banks 1957, 1960).

On the whole, castes of the Ksatriya and the Vaisya varnas - the ones who

would be legitimately entitled, in the Sastric sense, to claim the privilege

of domination-have been absent or nearly so in the South (Mandelbaum 1970:I,

23; Dumont 1981:73).

The Tamil social formation has often been characterized in Sastric

terms as comprising only Brahmans, Sudras, and Untouchables (Beteille

1969:3), but even this formulation obscures far more than it clarifies. It

takes no account, for instance, of the persistent and enigmatic distinction

of castes into "right" and "left" categories, a distinction that in fact

represents one of the most important and pervasive social features of the

South Indian system (Beck 1970). It is quite evident that, in

contradistinction to North India, the actual caste system of South Indian

villages can be interpreted even by the most sympathetic analyst to conform

only vaguely to the Sastric ranking paradigm.

The high rank of Sudra dominant castes perhaps best characterizes the gap

between the Sastric ideal and southern practice. Claiming as they do a rank

and a set of privileges that lacks scriptural foundation, Vellalars and

other South Indian Sudra cultivating castes would appear to be engaged in

what can only be described as a wily subversion of tradition, relying on

their wealth, the coercive force that they possess, and their

stranglehold on the land to guarantee their seemingly inflated status claims.

Precisely this case has been made, for instance, by Mandelbaum with

regard to the Sudra dominant caste of a village in Andhra Pradesh:

The dominant landowners there are Raj Gonds, a jati [caste] of tribal

origin. When Dube studied the village in the early 1950's, the Raj Gonds

were still performing cow sacrifice and eating beef, traits that would

have consigned them to the lowest depths of defilement among other

Hindus. But in this village Hindus of all but two jatis took water from

them [a gesture conceding the water-giving caste's superiority] and the

lower jatis also took food from them.. . . The example of the Raj Gonds

indicates that under especially strong conditions of power, even the

most heinous of polluting acts can be overlooked by otherwise orthodox

Hindus (Mandelbaum 1970:I, 208).

On the surface, this interpretation of the evidence has much to recommend

it, not in the least because it resonates so well with the common-sense

notion Western scholars have of power and its role in human affairs. The

Sudra, as we have depicted him, has seized for himself and his caste fellows

a privileged rank in village social life; his aim, we assume, is mastery and

domination over those his endeavors expose to be weak. His claim to purity,

no less than his claim to his laborers' impurity, is (as some would say of

all such claims by the powerful) an artifice: "more or less cunning," as

Geertz has put it, "more or less illusional, and designed to facilitate

the prosier ends of rule" (1980:122). To depict the strategy of Sudra

domination in these terms is to suggest that it is founded not on shared

belief and consensus, but rather on delusion and coercion.

It is therefore not surprising that Mandelbaum has interpreted the

political role of the dominant caste as one of "regulation," emphasizing not

the ideology of rule so much as its coercive foundations.

A truly dominant caste, lie notes correctly, is willing and able "to

field a band of determined men who will discourage dissidents by force. .

.[and] dispossess other villagers of their livelihood" (1970:I, 358-59).

From this interpretation emerges a view of how Sudra domination has been

reproduced over the centuries, despite its lack of legitimacy in traditional

ranking terms. Sudra domination has persisted, it would appear, because the

power of the dominant caste in its village has been so pervasive and so

adept that the dominated have been forced to accept it, even though it

cannot be justified by reference to the religious notions of rightful

domination that can be found in the Dharmasastras.

Against this interpretation it can be argued, as would Dumont (1981:153),

that even though the Sudra dominant castes of southern India do not claim

the Ksatriya rank they nonetheless seek to emulate the legitimate function

of Ksatriyas, for whom a certain dispensation is made with regard to the

niceties of purity restrictions.

After all, a ruler can hardly be expected to do his job if, like the

Brahman, he must live the Sastra-mandated life of plain living and nigh

thinking. He must be a man of action, and indeed the texts depict the king

expressly as immune to impurity (asauca) because he was pervaded with the

power of the gods (Gonda 1969:15). That power was conferred upon him in the

royal installation ritual (Inden 1978:28ff).

There is no small evidence that the Ksatriya dominant castes of North

India indeed deem themselves to possess a right to ignore purity

restrictions. The North Indian Rajput, for instance, "regards it as a kind

of warrior's dispensation that he is permitted to hunt, eat meat, drink

liquor, and eat opium" (Hitchcock 1958:220, cited in Mandelbaum 1970:I,

207). In Central India, Rajputs, notwithstanding their impurity, claim to

rank higher than members of other non-Brahman castes that emulate the purity

ideal, and the consensus of public opinion is in agreement (Mayer 1966:35).

It would appear, then, that there exists a traditional basis by which the

dominant "warrior" or "royal" castes of Indian villages may ignore purity

rules and yet claim high rank: they aim to "reproduce the royal function,"

and therefore are exempt from purity restrictions (Dumont 1981:291).

Nonetheless, there is clear and compelling evidence that this

interpretation, applied to the Sudra dominant castes of the south, flies

in the face of the social facts. Traditional Sudra powerholders,

epitomized by the dominant Vellalar castes of Tamilnadu, do not conceive

themselves to be eligible for the crown (Thurston 1909:VII, 363) and

have seldom claimed membership in the Ksatriya varna (Beteille 1969:97).

Nor do they fancy themselves to be "warriors."

It is true, to be sure, that warlike castes such as the Kallars and

Maravars of

South India maintain a martial tradition and deem themselves to be

Ksatriyas, but the Ksatriya model of domination has never found currency in

the heartland of the South, the rice-growing lowlands (Stein 1980: 70-71).

As will be seen, Kallars are peripheral to the agrarian social formation

with which we are concerned.

The dominant non-Brahman castes of the southern heartland, epitomized by

the Vellalars, have for two millenia regarded themselves (and have been

regarded) as people of peace. In one of the early Tamil texts,

Tolkappiyan's grammar, Vellalars were expressly differentiated from

warriors, and of them it was said that they had no other occupation save the

tilling of the soil (cited in Thurston 1909:VII, 369).

One and one-half millennia later, the Madras Census Report described

Vellalars in terms that well apply to the Vellalars of Jaffna today: "a

peace-loving, frugal, and industrious people" (cited in Thurston 1909:VII,

370).

We would seem to be left, then, with Mandelbaum's suggestion that

temporal power elevates the rank of the impure, and that the dominant

caste's claim to be "pure" is little more than artifice invented to

clothe its naked power in the fabric of traditional authority. This

authority-seeking strategy does not, however, wholly overthrow the

classical ranking scheme, for the dominant caste still recognizes and

honors the Brahman's absolute superiority.

For Dumont, the ranking situation in villages controlled by the dominant

caste shows that, while the classical tradition provides the ultimate ground

of ranking ideology, naked force makes itself felt in the middle range of

the caste hierarchy and "distorts" the classical scheme (1981:153). For this

reason, Dumont argues, we must acknowledge the presence on the Indian

scene of a "shamefaced," but nonetheless present, version of the

self-interested, arbitrary calculation and action associated with the

bourgeois individualism of the modern West (1981:353).

The role of South India's dominant castes in distorting the traditional

Sastric ranking framewok is witnessed, Dumont suggests, not only in the

artificially high rank of the dominant caste itself, but also in the

artificially low rank of certain dominated Untouchables.

To be sure, Paraiyars, the lowest of castes among Tamils, possess a rank

that would seem genuinely to reflect the absolute odium of impurity.

Yet throughout southern India, there are certain Untouchable castes,

nominally impure, whose status is not explicable in the Gangetic religious

framework. Sudras call these castes, epitomized by the Pallars, "impure"

(tuppuravu illai), pointing out, for instance, the castes' allegedly unclean

occupation, their shoelessness, their partial nudity, their non-vegetarian

diet, and their close identification with rituals involving blood sacrifice.

On close inspection, however, it is very difficult to tell just why it is

that these traits are impure-particularly when many of them are also carried

on by respectable Sudra landholders.

Consider, for example, the traditional status of the palmyra-climbing

Nadars of Tamilnadu. Of them it was said in the Ramnad Manual that they

were, in the nineteenth century, "inferior to Sudras and superior to

Parayas" (Hardgrave 1969:21, n. 17). The Bishop Caldwell noted their rather

anomalous status:

In some respects the position of the Shanars [Nadars] in the scale of

castes is peculiar. Their abstinence from spiritous liquors and from

beef, and the circumstance that their widows are not allowed to marry

again, connect them with the Sudra group of classes. On the other hand,

they are not allowed as all Sudras are, to enter the temples; and where

old native usages still prevail, . . . their women, like those of the

castes still lower, are obliged to go uncovered from the waist upwards

(cited in Hardgrave 1969:22).

Notwithstanding their estimable customs, it could be claimed that the

Shanars' impurity stems from their occupation: tapping palmyra trees for

toddy, an alcohol-hearing drink. Liquor is specifically condemned in the

Dharmasastras as an impure, foul substance. And yet the toddy they tapped

was no doubt destined for Sudra consumption, a point that Caldwell failed to

appreciate. If it is polluting to tap toddy, then surely it is even more so

to drink the fermented beverage. Yet Sudras, particularly powerful,

landholding Sudras like the Vellalars of Tamilnadu, rank very

high-notwithstanding the fact that, in reality, their domestic customs in

cuisine and ritual are hardly distinguishable from "Untouchables" like the

Nadars.

It would appear, then, that the higher-ranking Untouchables are "impure"

only because powerful Sudras wish to call them impure, and so degrade them

to the Sudras' servitude. Toward this end, it has been argued, landholding

Sudras force these "Untouchables" to demarcate themselves in public as

equivalent to Paraiyars: like Paraiyars, for instance, Nadars were

traditionally forbidden to wear shoes and, in consequence, it is said of the

Nadars that they are impure. But, as Louis Dumont has noted, wearing

shoes-even leather ones, leather being very odious to a strict Hindu-can

hardly be said to degrade an Untouchable vis-a-vis Sudras:

In the . . . district of Tinnevelly, I saw the marks of blows on the

back of an Untouchable, blows which he had received for having crossed

the village of a martial caste (the Maravar) wearing sandals. The

inhabitants themselves wear leather sandals, blows have never removed

impurity, and it is clear that the village was not polluted, but that

villagers had simply wanted to uphold a symbol of subjection (Dumont

1981:82).

According to Dumont's interpretation, the features of dress that powerful

Sudras impose on castes like the Nadars are only apparently sensible in

terms of the Gangetic notions of pure and impure. At first sight, these

imposed features would seem to be "particularly clear examples of

hierarchy." Yet, Dumont asserts, "closer inspection shows that these

features derive more from power than from the hierarchical principle"

(Ibid.). They do not issue from custom, although they are phrased in terms

of it, but rather from the desire of the dominant caste to regulate and to

subordinate persons who, by being linked with Untouchables, can be exploited

for their labor.

What is so striking about the South Indian system, then, is that its

anomalous ranks display a very intriguing reverse symmetry. The Sudra

landholding caste presents itself as "pure" and wins a rank second only to

that of the Brahmans; the toddy-tapping Untouchables are presented as

"impure" and win a rank penultimate to the lowly Paraiyars (Figure 1).

|

Caste Rank Presented in Terms of Purity |

| | |

| |

| Life Style Exemplifies Purity |

Life Style Exemplifies

Impurity |

| | |

| |

| |

| |

| Brahman |

Sudra Dominant Caste |

Higher Ranking Untouchables |

Paraiyar |

Figure 1 - The Symmetry of Rank in the South Indian Social Formation |

While the status of the Brahman and Paraiyar would appear to be

explicable in terms of the Gangetic ranking ideology, the two anomalous

ranks quite clearly contradict it. [It could be argued that the Sastric

ranking paradigm still applies in that Vellalars and Pallars exhibit,

respectively, less purity than the Brahman and less impurity than the

Paraiyar, and that the two castes therefore deserve the medial positions

that they occupy in the hierarchy. But to do so ignores the truly anomalous

feature of the Tamil ranking paradigm, for Vellalars rank higher than

genuinely pure non-Brahmans, just as Pallars rank lower than genuinely

impure non-Paraiyars.]

The consensus of scholarship on this curious pattern is that The

Symmetry of Rank in the South Indian Social Formation the power held by the

landholding Sudra caste of an area permits them to grant themselves a very

high rank, one that they do not deserve, while at the same time degrading

the rank-one equally undeserved-of the toddy-tapping Untouchables. This

warping of the hierarchical principle does not, however, wholly overthrow

the Gangetic framework. At the extremes of the hierarchy, the Gangetic

principles hold; in the middle, they are controverted by a substratum of

power.

Whatever magnetic attraction this view of the evidence may hold

for us, it is well to remember that in embracing it we shirk the

challenge of understanding South Indian culture as a genuine variant of

the Gangetic mold. We have denied, a priori, any uniquely Southern

cultural understanding of the two anomalous ranks.

There is, to be sure, much apparent credit to the argument that no such

cultural understanding exists, for it is not represented in Dravidian

languages of caste relations. In Jaffna, for instance, Hindus use the

ranking paradigm of the Dharmasastras - especially the concepts of purity

(cuttam) and impurity (tittu or tuppuravu illai) -to describe the statuses

of Vellalars and of Pallars, notwithstanding the concepts' inaccuracy. Yet,

if we are to accept the argument that a cultural understanding can be

demonstrated to exist only when we have discovered linguistic terms that

label it, we must assume, in the face of all the evidence for a regional

cultural tradition, that South Indian thought has made no contribution to

the cultural understanding of caste in the Dravidian lands.

There is - thanks to major, recent advances in social anthropology -

another kind of language to which we can listen: the language of ritual.

Leach, for instance, has defined ritual as that aspect of customary

behavior which communicates something, and argues that ritual plays an

essential role in social relationships by reaffirming (often by

exaggerating) status differences (1968:524).

Throughout southern India, people of many different castes have roles to

play in village ritual events, both in the context of household and of

temple rites. If these rituals communicate the meaning of traditional status

arrangements, then through an analysis of them we may learn something about

the Dravidian understanding of caste statuses.

That these rituals do indeed state a Dravidian ideology of caste

relations is the contention of this monograph.

Through an analysis of the rituals carried on by the Sudra cultivators of

Sri Lanka's Jaffna Peninsula, the center of Tamil culture in that island

country, I wish to show that there is a Dravidian cultural understanding of

Sudra domination and of the two anomalous statuses, one that invests them

with the deepest religious meaning and with the most profound legitimacy.

At once true to its Hindu sources and its Dravidian roots, this

essentially southern caste ranking tradition does not stand in conflict with

the Sastric tradition, but on the contrary extends and develops the

classical tradition within the framework of a distinctively Dravidian world

view. An analysis of this tradition helps us to understand, furthermore, not

only the curious forms of the southern caste system, but also other aspects

of southern social life (such as the distinction between "left" and "right"

castes) that have thus far resisted analysis. To grasp the religious

foundations of Sudra domination is to grasp, as well, the place of the

Dravidian cultural design within the overarching confines of the Hindu

cultural universe.

[Because I intend to unmask an essentially Dravidian ideology of caste

ranking-an ideology that represents a fundamental recasting in Dravidian

terms of the Sastric tradition-I have not attempted to assess the utility

for this project of the "ethnosociology" school of caste studies associated

with the recent work of McKim Aiarriott (1976). That school assumes the

Hindu ideology of caste relations to be codified in the Dharmas'astras, an

assumption that for crucial methodological reasons I am here unwilling to

make. Nonetheless, it will become clear in the pages to follow, at least to

those familiar with Marriott's theory, that this study bears implications

for the ethnosociology project (once it is made more sensitive to regional

variation), but it is not my aim here to assess them.]

The idea that there is a "Dravidian substratum" underlying the customs of

southern India, notwithstanding their northern veneer, has prompted a great

deal of fruitless speculation-so much so that, in fact, modern scholarship

tends to shy away from it. For many years, Indology seemed to assume that

anything and everything that could be defined as "civilized" was of Aryan

origin, while all "primitive" customs-such as, for example, shamanism, blood

sacrifice, or even (in some accounts), the puja ritual-were Dravidian.

An account of the ethnocentric, if not blatantly racist, assumptions

underlying these definitions would constitute a valuable contribution to the

sociology of knowledge. Gonda (1965), in a masterly essay, has shown very

convincingly that the customs of modern Hinduism such as puja, which are

thought to stem from Dravidian influence on the formerly pure Vedic religion

of the Aryans, can in fact be shown to be entirely consistent with the

orthodox, Gangetic tradition.

Yet not every aspect of the southern caste system is consistent with the

classical social thought of Gangetic India. If we are to assume that the

varna"srama dharma, with its social code calling for hierarchy and

interdependence on the basis of birth-ascribed groups, is the only possible

ideology of caste in Indian civilization, then we are left with only one

recourse when confronted with the South Indian evidence.

We must explain the discrepancies between Gangetic code and the

southern practice by reference to the Sudras' willful manipulation of their

tradition to suit their political and economic goals. For many, this

interpretation may seem quite satisfactory.

And yet it resonates, perhaps too well, with the Western (and

particularly the British and American) notion of Economic Man, who is

forever and everywhere poised in tension with his cultural traditions as he

attempts, as it is said, to "maximize" his wealth and power.

Remarkably enough, Dumont himself-an author who has more clearly than any

other called into serious question the relevance of the Economic Man model

to South Asian ethnology-has, when faced with the scarcely traditional rank

of the non-Brahman landholding caste, admitted the existence of a sort of

"maximizing," one carried on within cultural limits, on the Indian scene.

Whatever position one wishes to take on the universality of Economic Man,

it is my conviction that, as a fundamental principle of anthropological

methodology, we should not use a theoretical construct that we suspect to be

ethnocentric until we have at least explored the alternatives. At the

present time the option open to us, as Dumont himself has recently and very

clearly foreseen, is to study regional patterns and configurations of caste

in terms of regional ideological traditions (1981:xxxvi). And that is

precisely the area of this study.

The Rise of the Dravidian Social Formation ...

.... The rise of the Tamil social formation as we know it today may be

traced, according to Stein (1980), to the period subsequent to the Cankam

era, when Brahmans became important figures in rural affairs. By the eighth

or ninth century A.D., there had crystallized throughout the Coromandel

Plain an agrarian social order which was to endure without radical

alteration for one thousand years. This social formation, Stein has argued,

was the achievement of Brahmans, the carriers of the Gangetic tradition,

working together in the rural hinterland with their allies, indigenous

Dravidian cultivating groups (typified by the Vellalar).

The Brahman-peasant alliance was of mutual benefit to both parties.

Brahmans benefited from, the rich gifts and endowments peasants gave them

for temples and for their main tenance. Peasant cultivators benefited as

well, for reasons that are best understood when we consider the growth of

the agrarian order. Spreading out from the core centers of irrigated

agriculture, the agrarian social formation of early South India encountered

areas still inhabited by fierce tribal folk of the dry plains and hills. Not

only was it necessary to subdue these folk, but the conquered tribes had to

be assimilated into the agrarian order-ever voracious for labor-at the

lowest status levels, without threatening the status of the original peasant

cultivators (Stein 1980:73ff; Ludden 1978:5-8).

Brahmans provided these peasant cultivators with a ranking ideology that

defined the peasants as "next only to Brahmans in moral standing. They were

accorded the status of satvik, or men of a respectable way of life, and thus

distinguished from the lower orders of the population" (Stein 1980:84).

By the ninth century A.D. the social structure of this agrarian order in

the irrigated rice-growing regions had taken a clear and persistent form.

Its most important caste statuses, as Ludden has remarked, were the same

then as they were in 1900: Brahmans, Vellalars, Pallars, and Pariayars

(1978:5).

Rice and other lands were controlled, in the main, by groups of

Vellalars, who held hereditary rights (kani) to control agrarian production

on a particular plot of land (thus, kaniyatcikkaran, "land-controllers").

Since holdings were not allocated to individuals, but on the contrary only

to groups, membership in these Vellalar land-controlling groups was

tantamount to access to land.

Brahmans provided Vellalars with the ideology they needed to defend

their privileges and position by defining Vellalars as a morally excellent

and distinct caste.

In public ritual events at the temples, Vellalar donors were rewarded

with honors indicating their high status and legitimate rights. In return

for this service, Brahmans were accorded, by means of ritualized endowments,

legitimate claims to a portion of the Vellalarcontrolled harvest (Ludden

1978:5-5).

Pallar and Paraiyar laborers, who were being continuously recruited from

the periphery of the expanding order, were- if we may extrapolate from

contemporary evidence - similarly compensated by ritual allocations at the

threshing-floor distribution. They were thereby provided, to offset their

low status, with a secure niche in the local economy (Ibid., p. 8).

Accompanying the emergence of a definite Tamil social formation in the

irrigated rice lands was an enigmatic distinction between "right" (valankai)

and "left" (itankai) castes (Appadurai 1974; Beck 1970; Stein 1980).

Contemporary survivals of the division suggest that it represented a

thoroughgoing bifurcation of the social order into two rival segments, save

that Brahmans were deemed to stand above the split.

On the one hand were the "right" castes grouped around the dominant

Vellalar cultivators, who deemed themselves committed to reproduce the

social ideal of the classical Gangetic tradition. Among these castes the

predominant themes were agrarian ideals, a lusty involvement in life, lack

of concern with purity restrictions, and caste interdependence.

On the other hand were the "left" castes, led by the artisans, who

shirked the world of agrarian independence in favor of a town life

emphasizing the Brahmanical ideal of purity and saintliness.

However neat this pattern may appear, it was contradicted in the lower

status levels of the "right" division (Beck 1972). Pallars, closely tied to

Vellalars and representing the agrarian laborer par excellence, were-and

this is puzzling indeed-of the "left" subdivision (Stein 1980:477, Table

VIII-6).

Another persistent social cleavage was founded, as Ludden (1978) has

argued, on the ecological dichotomy of rice growing lowland versus dry

uplands. The characteristic social formation of the irrigated lowlands,

the hierarchical order of Brahmans, Vellalars, Pallars, and Paraiyars, was

not reproduced on the upland plains and hills. Agriculture there was

predominantly of the rainfall-dependent, slash-andaurn variety, which

requires little coordination of labor. The upland areas were controlled by

warlike castes such as the Kallar and Maravar, whose links with the

irrigated lowlands were few and antagonistic until the kings of the late

rnedieval period strove to subdue them.It was only in the irrigated lowlands

that anything approaching a well-integrated social order emerged.

In light of Wittfogel's analysis of Oriental despotism (1957), it is very

tempting to link the emergence of this "hydraulic society" to the

achievement of highly centralized state power. The kings of the period

indeed claimed for themselves exalted titles and enormous realms. Yet the

evidence strongly suggests a different picture. Throughout most of this

period the political organization of the Coromandel Plains resembled not so

much a centralized state as a chiefdom, with the territorial segments of the

agrarian order (the many natus) possessing almost complete autonomy. Far

from the royal center conditions doubtless bordered on statelessness (Stein

1977).

The agrarian order of the lowlands was integrated, Ludden (1978) has

argued, not by the political power of the state, but rather by means of a

comprehensive system of ritual entitlement. The constituent elements in this

ritualiy organized order were caste groups, whose status in the nexus of

social relations was defined and legitimated by moral and religious

valuations.

Brahmans, through temple rituals, invested Vellalars with the right to

control agrarian reproduction; by denying Pallars and Pariayars this ritual

entitlement, Brahmans condemned the laborers to landlesness, servitude, and

low status. So elaborate was this system of ritual entitlement that "every

inch of land, every act of public life, and every necessary interaction in

economic processes became infused with ritual meanings and moral valuations"

(Ludden 1978:6). And so effective was the ritual legitimation of rights and

statuses that no massive component of state power was necessary to buttress

the system of inequality or to organize public works. On the whole, the

system grew "in a cellular, segmented manner: similar, allied, but staunchly

independent units were merely added on as population and irrigated acreage

increase".(ibid., p.8)...."

|