|

Queimada - Gillo Pontecorvo's

Burn!

- as long as there are empires, there will be wars

-

[DVD available at Amazon.com]

Review by Joan Mellen

Courtesy: Cinema Magazine - Issue:32, Winter

1972-73

"..The film

portrays, quite brilliantly, the nature of a

guerrilla uprising. Walker seems all too aware of

the danger of a popular uprising, when he cautions

the white rulers that "the guerrilla has nothing to

lose." And that in killing a hero of the people,

the hero "becomes a martyr, and the martyr becomes

a myth." " Amazon Review

"... The young boy

who guards the captured Dolores stays with him and

provides Pontecorvo with a means of allowing Jose

Dolores to give his ideas expression through

dialogue. Jose Dolores does not assail his captor;

he tries to inspire and convert him. He tells the

young man that he does not wish to be released

because this would only indicate that it was

convenient for his enemy. What serves his enemies

is harmful to him. "Freedom is not something a

man can give you," he tells the boy. Dolores is

cheered by the soldier's questions because,

ironically, in men like the soldier who helps to

put him to death, but who is disturbed and

perplexed by Dolores, he sees in germination the

future revolutionaries of Quemada. To enter the

path of consciousness is to follow it to

rebellion.....Pontecorvo zooms to Walker as he

listens to Dolores' final message which breaks his

silence: "Ingles, remember what you said.

Civilization belongs to whites. But what

civilization? Until when?" The stabbing of Walker

on his way to the ship by an angry rebel comes

simultaneously with a repetition of the Algerian

cry for freedom. It is followed, accompanied by

percussion, by a pan of inscrutable, angry black

faces on the dock. The frame freezes, fixing their

expressions indelibly in our minds.."

Comment by

tamilnation.org

"..But imagine

it happens: Killinochchi is flattened,

Mr P is dead, LTTE

dissolved. Will the Tamil dream of a Tamil Eelam die?

Of course not. It will be revived, and new cycles

of violence will occur..."

Conflict Resolution in Tamil Eelam - Sri Lanka:

the Norwegian Initiative- Professor Johan

Galtung, February 2007

"Kuttimuni will be sentenced to death today,

but tomorrow there will be thousands of

Kuttimunis." Statement by Tamil Leader,

Selvarajah Yogachandran (Kuttimuni) at his trial

in the Colombo High Court, August

1982

Gillo Pontecorvo's Burn! must

surely be one of the most underrated films of recent

years. This can be explained in part by its involved

and intricate plot which, on first viewing, is

difficult to follow.

Sir William Walker (Marlon Brando)

soldier of fortune, adventurer and an envoy of the

British Crown is sent during the 1840's to an island

named Quemada. The island was originally burned to

cinder in the scorched earth conquest by the

Portuguese who claimed it as a colony- hence the name

"Quemada" which means "burnt."

Walker's mission is to foment a

revolution against Portugal among the oppressed

peasantry with a view to replacing Portuguese control

with that of Great Britain. He arms a peasant named

Jose Dolores whom he first tests for daring and

bitterness. With a small band of followers, Dolores,

guided by Walker, robs the Bank of Portugal of its

gold and goes on to lead the struggle against the

Portuguese. After victory, Dolores discovers that the

new ruler of the island will be not himself, but a

local bourgeois named Teddy Sanchez.

|

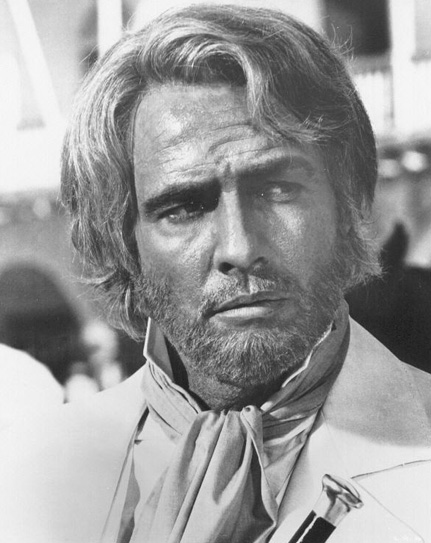

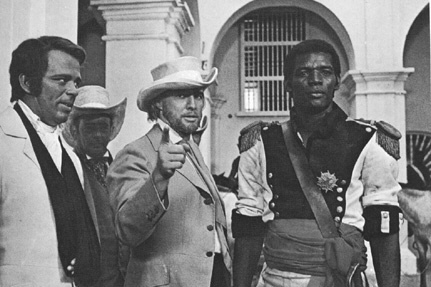

Marlon Brando as Sir William

Walker

|

Walker, having provoked peasant

revolt to remove Portugal, has organized the settler

bourgeoisie, warning them that the peasants will go

beyond independence, demanding economic and political

control to effect social equality. The settlers are

used by Britain to protect British investment and her

access to Quemada's resources.

"Independence" is translated into

replacement of Portugal by a small settler ruling

class militarily supported by Britain. For the

peasants, one master replaces another. Their misery

and powerlessness continue. It is a prefiguring of

today's neo-colonial pattern.

Dolores is outraged by this cynical

denial to him of the fruits of struggle and he

assumes the throne of the former Portuguese Viceroy

by force. But he discovers that although he possesses

momentary power, he lacks the means to feed his

people or to sell the sugar. There is no knowledge of

world trade or alternative markets. Teachers and

technicians do not exist. In short, his people are

without the very accoutrements of that civilization

which oppressed them in the first place.

Unable to see a way out and with

sugar rotting and piling up on the docks, Dolores

steps down reluctantly, allowing Sanchez to take

control. But the settler commander General Prada is

quicker than Sanchez in realizing that Quemada can be

kept open to foreign investment and bourgeois rule

rendered secure only if the rebels are suppressed and

permanently disarmed.

Ten years pass. Walker, lacking apparent purpose in

life, is now dissolute and living on the margins of

English society. Jose Dolores again leads his

starving people in a new rebellion aimed directly at

the landed settler rulers. This threatens the entire

structure of British economic control with

implications reaching further than Quemada. Such a

revolt, if successful, would spread through the

Caribbean and beyond.

The British turn again to Walker, hoping to exploit

both his knowledge of the peasant movement and his

old relationship with Dolores. He is asked to return

to Quemada and put down the rebellion. Walker

accepts.

He attempts to contact Dolores,

thinking to trade upon their old association, but it

is this very past which has opened the eyes of

Dolores to Walker, whom he spurns.

Now openly the professional

mercenary, Walker pursues Dolores ruthlessly, burning

half the island while uprooting and killing people,

animals and vegetation in his path. He develops a

theory that the guerrillas can be defeated only if

the peasants among whom they take shelter and who

supply them are burnt and driven out of all their

villages. The vegetation and trees must be denuded

since they too hide the rebels. The logic of

defeating a popular movement is inexorably genocidal,

entailing total devastation.

Dolores is finally captured and

hanged, refusing Walker's "offer" to escape. Dolores

has learned that freedom must be seized in struggle.

And he knows the offer to free him is designed to

demonstrate his subordination. He also realizes that

Walker, having smashed the rebellion, wants to avoid

creating a martyr and a legend. Dolores, in cool

defiance, prefers death as his fulfilment.

Walker is personally undermined by

this stark contrast between Dolores' satisfaction in

moral conviction and his own emptiness, which he only

now fully registers. The taste of victory is

bitter.

His business finished, Walker is stabbed to death on

the dock by a porter a moment before embarking.

Quemada's people are awakened, emboldened, and

irreconcilable. The camera pans to many worn faces,

their rebellion unchecked and the example of Dolores

burned into their consciousness.

The political aspirations of Burn!

are ambitious. Unlike The Battle of Algiers,

Pontecorvo's earlier film, which takes the easier

target of colonialism and the desire for

independence, without examination of social

formations or the political consciousness of the

F.L.N., Burn! recognizes that direct colonial rule is

but one form of control.

Without goals that go beyond mere

physical absence of the colonizer's army, economic

and social exploitation will be maintained for alien

interests by intermediaries, independent in name

alone. Neo colonialism is shown a

far more invidious and clever enemy.

The powerful evocation of the

dynamics of America's practice in Vietnam, with its

graphic depiction of "Vietnamization," must surely be

a major reason for the critical skittishness towards

Burns! in this country.

Pontecorvo has Walker make his next

stop Indochina on first leaving Quemada, a piece of

historical impressionism, since France and not

England occupied Indochina in the 1840's. It is a

bitter irony when his friend Jose Dolores, not yet

awakened to betrayal, innocently offers Walker a

toast "to Indochina."

United Artists, as Pauline Kael put it, "dumped" the film

without advance publicity and screenings. They made

Pontecorvo change the occupier from Spain to

Portugal, presumably because the Spanish market for

all United Artists films was in jeopardy.

They made the English title of the

film the absurdly imperative "Burn!" rather than the

appropriate translation, "Burnt," which states the

inexorable fact, thus implying the film's endorsement

of the tragedy it depicts.

Involved too is the crass

sensationalism of invoking "burn, baby, burn" of

ghetto insurrections. This, aimed at the black

market, inverts the film's meaning, for Portugal and

Britain burned Quemada, not the victimized populace,

who would never call for the "burning" of their own

homes.

Burn! may have been buried because

United Artists doubted the film would do well, but

the distributor willed its unhappy fate. They were

disturbed by the incendiary nature of a subject with

which they did not care to be closely identified.

If Portugal and England were safer

destroyers for United Artists, the film's relentless

association of racism (the condescending attitude of

Walker toward Jose Dolores throughout) with

imperialism brought the theme even closer to home.

The Battle of Algiers, despite

its acclaim, had already suffered a distribution and

publicity blackout in the United States, and Burn!

goes deeper and farther.

Here, far more than in Algiers,

Pontecorvo explores Fanon's theme that through long

delayed and liberating violence the oppressed are

returned to self-respect and adulthood. After

attacking their first detachment of Portuguese

soldiers, Dolores and his people burst into an orgy

of dance and song that lasts far into the celebrating

night. After generations of passivity before abuse,

they emerge as autonomous people. It is entirely

possible that there are circumstances in which a

company like United Artists might even be prepared to

lose money!

What makes Burn! more interesting than The Battle of

Algiers is that it raises those questions which

Algiers, in its more pristine detachment, evades.

The problem of what happens when a

revolutionary organization takes power in an

over-exploited country is hinted at in Algiers when

Ben M'Hidi advises Ali La Pointe:

"It's difficult to start a

revolution, more difficult to sustain it, still

more difficult to win it," but it is after the

revolution that "the real difficulties begin."

Burn! takes on this challenging

theme. One of the film's most subtle insights is that

colonialism so succeeds in damaging its victims that

should they take power, they have in advance been

deprived of the means of exercising it.

"Who will run your industries, handle

your commerce, govern your island, cure the sick,

teach in your schools?" Walker asks Jose Dolores,

confident of his superior position. "That man or this

one?" he continues, pointing contemptuously to the

bodyguards of Dolores who stand helplessly before

him. "Civilization is not a simple matter. You can't

learn its secrets overnight."

Burn! is an intensely romantic movie, a seeming

contradiction given the relentlessness of its

politics. It opposes "Western Civilization" (an evil

because it has been racist and exploitative) to the

purity of its victims, who can see nothing of value

in a civilization which forever holds them down.

But the sugar cane cutters are the

true creators of the civilization which they reject

as "white." "We," declares Jose Dolores to Walker,

"are the ones who cut the cane." The labor which has

led to great wealth is subsequently denied its

producers. That it could not exist without them

slowly dawns upon Dolores as a transforming

discovery. From this flows confidence and single

mindedness.

Pontecorvo unfortunately makes a facile

identification between liberation for Quemada's slave

descendants and a rejection of "white

civilization."

Because the vast wealth exacted by

colonial countries from the labor of their victims

has given rise to a flourishing culture, it does not

follow that the arts, sciences and technology made

possible are themselves hateful. The fact that white

Europeans are associated with this civilization

accounts for the racism of the Europeans, who must

denigrate those from whom they plunder, but it does

not validate a racism in inverted form.

This is what Pontecorvo unwittingly

does when he allows Dolores to prophesy not merely

the end of an order which depends upon exploitation,

but also the culture which it has spawned. Since all

culture has similar origins, the sentiment casts the

advocate of emancipation in the role of

destroyer.

But the burden of the film is to

present Dolores and his people as the carriers of a

different society, one which would end exploitation

and create a corresponding culture. It is clear that

the accumulation of capital, which permits technical

development and a culture requiring leisure, draws

upon this labor. The social basis of Western

Civilization, certainly in its industrial and

technological phase, is traced in Burn! to its brutal

source.

The last words of Jose Dolores are

meant to taunt Walker with his obsolescence:

"Civilization belongs to whites. But what

civilization? Until when?"

The words fall short, although they

gain power as the last statement of a man giving his

life to his deepest convictions. Because the film

raises this idea without exploring it, the source of

the projected new civilization remains obscure - as

it must - for it is surely destined to take the best

of bourgeois culture as a point of departure rather

than retreat, if it is to be a culture transcending

the subjugation of one class by another.

Pontecorvo has said that "the third

world must produce its own civilization and one of

the weaknesses of the third world today is that its

culture is not a new product which has rid itself of

white culture, but is a derivation of this culture.'"

But an emergent people will take what is useful to

them and build from there. In any event, no culture

is a new product. Such a view is hardly historical,

let alone Marxist.

And, Pontecorvo, after all, in describing the

struggle of Jose Dolores, projects not a "new"

ideology but that of Marx, who was both European and

a product of European capitalism and civilization.

"Between one historical period and another," says Sir

William, readying himself for battle against Dolores

and the rebels, "ten years may be enough to reveal

the contradictions of a century."

Pontecorvo applies the words of Marx, as well he

might, since a new ideology is not required. Nor does

Pontecorvo care that Walker uses Marxist terminology

and categories before the Communist Manifesto was

written!

Why then does he, speaking through

his characters, offer in the film a blanket

condemnation of all the ideas, values and

philosophies to appear in Europe since the Greeks?

"If what we have in our country is civilization,"

says one of the rebels, "we don't want it." Yet in

the next breath his ideas are those of Marx and

Engels: "If a man works for another, even if he's

called a worker, he will remain a slave."

These contradictions permeate the

film and engender not only a certain feeling of

anachronism, but a lack of intellectual clarity,

especially disturbing in a film which aims to enlarge

our understanding of the nature of neo-colonialism

and its relation to culture. There are other

undeveloped aspects of the film.

In the service of Britain, Sir

William Walker is ready to kill Jose Dolores when he

threatens British privileges and interests. But

Walker feels deep affection for the rebel leader who

has played Galatea to his Pygmalion. Indeed his

fondness for Dolores is almost as obsessive as his

later quest to capture him, and, at the end, Walker

is shattered by Dolores' contempt. This is one of the

most potentially illuminating and subtle themes in

the film.

Walker's fascination with the

vitality and innocence of Dolores is in counterpoint

to his frenzy when he is rejected, even as the

colonizers want the love and approval of those they

oppress at the same time as they would destroy them

for exposing the perpetrators to themselves.

This allows psychological

verisimilitude to Walker when he returns to Quemada

as a ruthless warlord who will burn every blade of

grass to prevent Dolores' rebellious ideas from

spreading to other colonies and islands where Royal

Sugar maintains interests.

A major weakness, however, is that

this ambiguity of response is evident in Brando's

performance, but inadequately developed in the film.

The problem is that the face of Brando easily conveys

irony and nuance. He is at his best when a situation

is ambiguous.

But the film seems to deny ambiguity

when we are expected to believe that Walker, without

self-examination, will renounce all humanity in the

service of an absent master- for pay so meagre it is

not enough even to be called "gain."

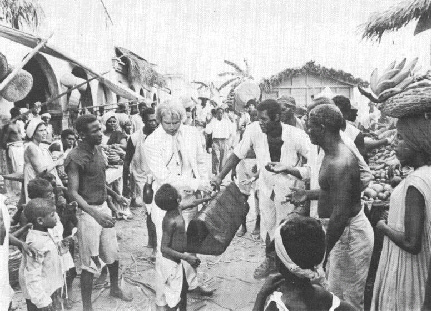

Sir William Walker (Marlon

Brando) meets the porter Jose Dolores (Evaristo

Marquez) |

Psychological motivation required

more careful delineation. As it stands, in the middle

of the film Brando, is unable to carry the

degeneration of Walker when he has become a brawling

drunkard. The action and melodrama, no matter how

many fires are set, is too weak to conceal the hiatus

between one aspect of the characterization, the

external, and the other, the inner life of

Walker.

The bridge of a psychological

relationship between Walker and Dolores, oppressor

and oppressed, is not constructed. Pontecorvo is

himself too facile in accounting for Walker's

transformation:

"Walker changed because he discovered

that there was nothing behind the side he helped...

Men like Walker, full of vitality and action, then

change the direction of this vitality. They go to

sea, buy a boat, drink, beat people up. They don't

believe in anything.'"

This is meant to explain why Walker returns to work

for Royal Sugar to rid the island of its rebels, i.e.

to a man empty of values one side is not perceptibly

different from another. But this reduces Walker to a

cardboard figure, and Brando is uncomfortable with

the conception, imparting to his Walker that very

psychological nuance which the film itself does not

consistently fulfill.

Hence we miss in Burn!, until the

very end, that moment of self-confrontation and

discovery in which Walker registers his emptiness and

becomes ready to do anything.

We have instead his departure to

"Indochina" in one sequence and the sight of a

slovenly Brando in the next. There is almost a

suggestion here that Pontecorvo fears that moments of

psychological insight in a film involve indulgence, a

resort to what vulgar Marxists might call "bourgeois

individualism."

More the pity, because the spectacle

of personal damage drawn upon and inflicted by

imperialism upon its own adherents could only have

made more rich the portrait of deterioration in so

bold and talented man as Walker. Given the enormous

resource Pontecorvo had in Brando, he neglected an

important opportunity to create a character at once

more powerful and tragic for being able to see more

deeply into himself.

As in Algiers, Pontecorvo used primarily

non-professional actors in Burn! Besides Brando, the

only professional was Rento Salvatori who plays the

social democratic leader Teddy Sanchez, an easy tool

who is eliminated when he perceived: "if there had

not been a Royal Sugar, there might not have been a

Jose Dolores."

General Prada was played with wit and

aplomb by a lawyer, the President of Caritas in

Colombia. Mr. Shelton, the representative of Royal

Sugar who accompanies Walker during the last half of

the film, was performed by the administrator for

British Petroleum in Colombia. He played

himself-convincingly and with ease. Only in Evaristo

Marquez (Jose Dolores) was Pontecorvo unlucky.

"...the native population scrounges for a

living on the waterfront. It is here that

Walker meets Jose Dolores, a porter who has

learned that the only way to survive in a white

man's world is to ingratiate yourself with

foreigners." |

In Algiers, Brahim Haggiag, an

illiterate peasant who knew nothing of movies, was

metamorphosed into Ali La Pointe in every gesture and

expression. Marquez was also an illiterate peasant

who had never seen a movie when Pontecorvo met him.

He was chosen without a screen test because his face

so well suited Pontecorvo's conception of the

character. But here the attempt failed. Pontecorvo

found that Marquez could not turn or move on cue. A

script girl had to tap his leg to remind him of his

next movement.

His part had to be played over and

over in the evenings by Pontecorvo and Salvatori.

Brando, out of the frame, would mime the facile

gesture for Marquez who was on camera, while

Pontecorvo shot over Brando's shoulder. Although

Pontecorvo argues that after ten days Marquez

improved dramatically, the film is marred by the

unevenness of his movements and the unsureness with

which he speaks.

At one point during the shooting, when Dolores was

being coached in a completely mechanical way, Brando

quipped, "If you are successful with this scene, I

know someone who will turn over in his

grave-Stanislavsky."

Unfortunately for Pontecorvo,

Stanislavsky's rest was not disturbed. It is not even

clear from his performance if Jose Dolores

understands what the film represents as his

ideas.

In the course of Burn! Dolores must

mature- from a man without consciousness of his

condition, completely unaware of the nature of his

enemy, to a seasoned leader who knows exactly "where

he's going," even if he's not always sure of "how to

get there." He is to emerge as a mass leader. But

with Dolores, and sometimes with Walker, motives and

feelings are too often presented in long shot. We do

not in fact see what we are told is before us.

Despite these weaknesses, Burn! is a beautiful film.

It shares many of the strengths of Algiers, but its

historical scope is far wider than the bare theme of

independence from an oppressor long condemned by

history as obsolete. A remarkable feature of Burn! is

its truly cinematic style.

Pontecorvo interweaves his two great

preoccupations, music (and sound in general) with the

imagery created by a constantly moving camera. The

result is not a tract against neo-colonialism, but a

ballet in which the dancers perform in accordance

with a scenario predestined by the exigencies of a

historical determinism.

During the course of Burn! the visual

style is altered with the changing fortunes of Jose

Dolores. Walker's arrival in the first sequence is on

a "painted ship upon a painted ocean." Birds chatter

peacefully overhead and the camera pans a lush, green

island. His second arrival, when his mission is to

exterminate Jose Dolores and the revolutionaries, is

in fog and mist, "under a cloud."

The terrain of the last scenes of the

film contrasts sharply with the first. All color has

been bleached out. The sky is not blue, but white.

The birds fly up to the sky to escape the smoke.

Vultures predominate as the screen is filled with

bodies and there are only blackened, charred trees.

Pontecorvo demands of his camera that it find visual

equivalents for the emotions of his people.

" 'Between one historical

period and another,' says Sir William, readying

himself for battle against Dolores and the

rebels, 'ten years may be enough to reveal the

contradictions of a century.' " |

But beyond cinematography, Pontecorvo

uses sound, and frequently music, to convey the

themes of his films. He admits to whistling projected

musical themes on the set during shooting to govern

his pacing, to determine how long to stay with a shot

or on a face and when to cut away. Burn! begins with

a gunshot heralding the titles which force their way

onto a screen fragmented with stills from the film,

one giving way to the next, in a violence accentuated

by red background and music. The effect is of a film

demanding that its message be seen and heard.

The central musical motif of the film, that

associated with Jose Dolores, begins when the captain

of Walker's ship points out to him an island in the

harbor where the bones of slaves who died en route to

Quemada are said to have been thrown. The music thus

is interested not in Jose Dolores as an individual

alone (he has yet to appear), but as a symbol of his

suffering people. In the same way Walker, who shows

Dolores' executioners how to tie the noose, ("See

Paco," says the man, "this is how they do it.")

personifies a vicious culture, a role that will

supersede his impulse of affection and sympathy for

Dolores.

Sound and image parallel each other as the thud of

the plank lowered for the passengers to disembark is

followed by a quick zoom back for a larger view of

the wharves of Quemada. Creoles await the ship in

eager anticipation, while the native population

scrounges for a living on the waterfront.

It is here that Walker meets Jose

Dolores, a porter who has learned that the only way

to survive in a white man's world is to ingratiate

himself with foreigners: "Your bags, Senor," are his

"smiling" first words. With a hand- held camera

Pontecorvo takes us on a tour of the market place of

Quemada, teeming with life, its bustle to be broken

shortly by the arrival of a gang of black slaves in

chains.

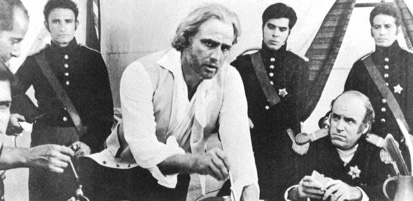

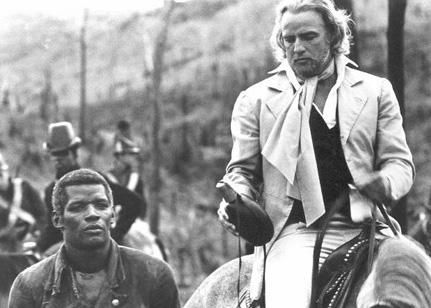

"Walker changed because there

was nothing behind the side he helped... Men

like Walker, full of vitality and action, then

change the direction of this vitality. They go

to sea, buy a boat, drink, beat people up. They

don't believe in anything." |

Pontecorvo uses the zoom even more

frequently here than he did in Algiers, and often for

the same reason, as a means of conveying a rapidly

changing state of consciousness in a character. There

is a zoom to Brando's eyes as he looks through the

bars of the windows at the funeral of the dead

revolutionary, Santiago, who, had he lived, might

have helped him in his plan to overthrow

Portugal.

The technique is also used with Jose

Dolores as he lifts a stone against a Portuguese

soldier mistreating a female slave. To emphasize the

moment in which Walker sees Jose Dolores as a

successor to the dead Santiago, Pontecorvo freezes

the frame. With Pontecorvo the freeze frame is used

as an equivalent to musical punctuation. Just as a

musical theme can begin and then cease, only to start

up again later, completing the motif, the freeze

frame can punctuate the visuals. At this moment in

the film the identity of Jose Dolores, and his

future, have been sealed by his act of attempted

rebellion.

Equally, Pontecorvo attempts to use editing as a

means of thematic expression. He cuts from the

bereaved wife of Santiago to a vulture against the

sky, as she carries the body of her decapitated

husband home. The vulture evokes the rapacity of

those who exploit the people of Quemada and who

murdered Santiago. Pontecorvo's editing style permits

him a good deal of foreshortening, especially useful

in a film with so complex a plot.

Walker teaches Jose Dolores and his

men how to use a weapon, concluding the lesson with

the words, "the rifle is ready." The rapid cut,

accompanied by percussion, is to a pan of the dead

bodies of the Portuguese soldiers who have been

killed as a result. Pontecorvo very frequently uses

percussion, as in Algiers, as a means of heightening

tension and emphasizing the crucial nature of an

action.

For his close-ups Pontecorvo generally relies upon

the eyes of his people. He chooses actors frequently

on the basis of the intensity and expressiveness of

this feature. The close-up of the eyes of Jose

Dolores as he is about to attack Walker, who has just

tested his metal by calling his mother a whore,

immediately conveys his fury. Close-ups emphasize the

tearful eyes of the children of Santiago helping

their mother to remove the body. They become the

tears of all those who have been made to suffer

meaninglessly.

" 'Who will run your

industries, handle your commerce, govern your

island, cure the sick, teach in the schools?'

Walker asks Jose Dolores, confident of his

superior position.. -'Civilization is not a

simple matter. You can't learn its secrets

overnight.' " |

Such moments are contrasted with

those in which Pontecorvo, using percussion,

emphasizes the vitality and life force in the

oppressed which emerges when they actively take part

in wresting their freedom. After the killing of the

Portuguese soldiers, Jose Dolores and the men and

women who have helped him break into a dance. In his

throat Jose Dolores echoes the shrill cry of the

Algerian women when they urged their men to avenge

the bombing of the Casbah.

Reminding us of the earlier film,

this scream from Dolores unites his struggle with

that in Algeria. It also provides Pontecorvo with

another opportunity to show that for people in

underdeveloped countries faced with colonialism and

later, neo-colonialism, the task is the same. The

process of self-liberation follows a similar pattern.

Jose Dolores dances with a baby in his arms, a

frequent symbol with Pontecorvo, expressing his sense

that the pain to be endured by Jose Dolores will be

unmediated by success; it will be for future

generations, who must continue his struggle, to

achieve the final victory.

The defeat of the Portuguese in the film occurs all

too quickly. It is rather inexplicable that a

military (and naval) power like Portugal could be

banished from Quemada with so little struggle or

attempt at reinforcement. On the night of a carnival,

the camera zooms in on the Portuguese governor about

to be assassinated, ostensibly by Teddy Sanchez, but

actually by Walker, whose role is epitomized as he

holds the unsteady arm of his co-conspirator.

Pushed out onto the balcony to face

the people, Teddy Sanchez utters a whispered

"freedom," displaying the timidity of his class faced

with mass insurrection. A waving flag of Portugal

appears mysteriously, providing the shot with rhythm

and color- and Sanchez with the opportunity to tear

it down. This action gives him his voice as well. As

he now yells for "freedom!" the drums begin,

expressing the restoration to life that liberation

grants the people of Quemada.

The sympathy of the director for Jose Dolores is

revealed most clearly in the music, resounding like a

Gregorian Chant and sung by a black chorus, which

accompanies Dolores and his army along the beach into

the city. Because the music is so flamboyant,

Pontecorvo begins with an extreme long shot of

Dolores and his people, some walking, some on tired

old horses, most in tatters, and all in absolute

silence.

Only when they are more nearly within

our visual range do we hear the first notes of the

organ which introduces the composition. The effect of

this music is extremely powerful, if romantic. It

succeeds, however, in rendering Jose Dolores a

beatific figure, possessed in his devotion of more

than human virtue.

To reinforce this transcendent

quality of his hero, Pontecorvo has a crowd of women

and children from the town run along the beach

greeting Dolores. The scene is done in silence with

music alone, recorded, interestingly, by Pontecorvo

in Morocco. It sets off the more grandiose music of

the earlier moment. Smiling women with tears

streaming down their cheeks reach out for Dolores, as

if they were touching a god. Shots of arms, hands,

parts of bodies, children, reinforce the motif of an

enormous collective force converging like a wave in

the struggle against exploitation.

Pontecorvo also relies upon reaction

shots to indicate the political point of view of the

film. Jose Dolores' face changes effectively (and

here Marquez seems quite adequate) when he learns

that Sanchez has been made President of the

Provisional Government.

But the best reaction shot in the

film occurs later, when a troop of British soldiers,

complete with Red Coats, disembarks from the ship

that has brought them to destroy the guerrillas. A

baby-faced young soldier, marching proudly along,

perhaps on his first assignment, smiles when he sees

all the beautiful, richly dressed women who have come

to offer welcome. His smile is slowly dissolved to an

expression of extreme fear as he sees the cold fury

in the eyes of the men of Quemada - also watching the

scene on the wharf.

The shot of the arrival of the

British Army, marching through a crowd of waving

handkerchiefs and cheers, parallels very closely the

appearance of Mathieu and his paratroopers in

Algiers. Both scenes establish that imperialism will

use all the force and technology at its disposal to

crush a rebellion aimed at removing its economic

domination of impoverished lands.

Because it reminds us so much of

Algiers, the scene in Burn! serves again to reiterate

Pontecorvo's view that the struggle of all these

peoples is fundamentally the same. Their enemy always

behaves in comparable ways because the objective of

domination compels essentially similar stratagems and

values.

Jose Dolores survives in power but a short time. The

insuperable quality of the obstacles facing him is

shown by the tracking camera moving through the

chaotic palace rooms filled with debris, men sleeping

on the floor, a howling dog, and general

disorder.

Dolores returns to the encampment of

his people while the musical motif which has been

associated with him is played, this time with pathos.

The scene is a tableau vivant; the people reach out

to him as they did on the beach. He smiles, but in

his heart he knows that their freedom, for now, will

be short-lived. The motif is again played with

sadness when later, in a flashback, the rebel army is

shown throwing down its guns.

Pontecorvo attempts to use music alone to convey the

reason for Walker's return to Quemada. During a

dissolute ten years, Walker had left the British Navy

to inhabit slums. He no longer lives in keeping with

the values and style of his class. The scenes which

take place in England look as if they were filmed at

the Cinecitta Studios outside of Rome. They are

unrealistic to an extreme, puffed with atmosphere and

fog, like Dickens seen through the eyes of Rebecca of

Sunnybrook Farm.

The credibility of the entire

sequence is saved only by the mobility of Brando's

face when he is told by the emissaries of the Royal

Sugar Company, now de facto ruler in Quemada, that he

is needed. Walker scorns the offer until he is

informed that it has something to do with "sugar

cane." His face immediately changes as he remembers

his days with Dolores. Accompanying his wistful and

pained expression is the musical motif that we have

associated with Jose Dolores and which represents all

that is cherished in the film.

It is with this that Walker identifies and which

possesses him. And it is here, in failing to develop

the personal workings of his attachment, that the

film appears arbitrary. Suddenly, in the next

sequences Walker becomes a hardened mercenary who

does whatever is necessary to preserve the holdings

of a ruthless and self-serving sugar company, not

caring what he must do as long as he "does it

well."

We are presented a second time through the music with

Walker's ambiguity. And again music alone cannot

carry an entire psychology of character. On his

return Walker sends a message asking Dolores to meet

him for a discussion. Dolores' outraged emissary

conveys the request (It will later be answered with

the murder of three soldiers). But before this

occurs, Walker, satisfied with himself and relishing

the opportunity to meet his old friend once more,

steps outside of his tent. He asks his sentry why he

"isn't in the Sierra Madre with the others." (The

name immediately suggests the " Sierra Maestra" of Cuba and

encourages us to see in Jose Dolores a forerunner of

Fidel

Castro).

The musical motif of Dolores once

more envelops Walker as he walks out to look at the

sunset. It is one of his moments of greatest

happiness in the film. The music poignantly expresses

the yearning in Walker, but it undercuts our belief

in the mission Walker carries out so relentlessly,

despite his feeling for Dolores. The element of

self-awareness is missing and with it a means of

integrating Walker's ambivalence within a coherent

depiction of his psyche.

Pontecorvo uses no dialogue to condemn the soldiers,

who must burn all of Quemada to capture Jose Dolores

and his band of guerrillas. It is the music which

judges them as they evacuate the villages. Sometimes

sound and image overlap to increase the sense of

irony.

At one point, as people are being

herded from their homes, we hear the words of the

next scene: Teddy Sanchez tells a crowd of starving

refugees, "You will know that it is not we who are

responsible for this tragedy, but Jose

Dolores."

A moment later a riot develops over

the distribution of a cart-load of bread and, upon

orders from General Prada, the people are fired on by

the soldiers. A man of good intentions, the social

democrat Teddy Sanchez, who believed all could live

peacefully together under the rule of Royal Sugar as

long as "adequate wages" were paid, is superseded by

the more realistic General Prada who has known all

along that Royal Sugar and a contented population

were irreconcilables to be mediated only through the

barrel of a gun.

At one point during the evacuations,

Pontecorvo tilts to a little boy with his hands up.

The "nota ten uta" or sustained note, accompanying

the image was written by Pontecorvo. He included it

in the film, as he says, "superstitiously," since

Burn! was the first of his films in which he did not

collaborate on the music because only two months were

available for the editing.

Pontecorvo zooms in on the young

soldier who captures Jose Dolores to explain the

willingness of young men in Quemada to fight for

Walker. One of Walker's soldiers declares he hopes

Dolores remains uncaptured because as long as Jose

Dolores lives, he has work and good pay. "Isn't it

the same for you?" he asks Walker.

The young boy who guards the captured

Dolores stays with him and provides Pontecorvo with a

means of allowing Jose Dolores to give his ideas

expression through dialogue. He does not assail his

captor; he tries to inspire and convert him. He tells

the young man that he does not wish to be released

because this would only indicate that it was

convenient for his enemy. What serves his enemies is

harmful to him. "Freedom is not something a man can

give you," he tells the boy. Dolores is cheered by

the soldier's questions because, ironically, in men

like the soldier who helps to put him to death, but

who is disturbed and perplexed by Dolores, he sees in

germination the future revolutionaries of Quemada. To

enter the path of consciousness is to follow it to

rebellion.

General Prada is persuaded by Walker that Dolores

induced to supplicate for freedom would serve their

purposes better than the creation of a martyr, his

spirit dangerously wandering the Antilles. Walker,

his ambivalence surfacing, does not want the blood of

Dolores on his hands. The scene in which Prada makes

his offer to Dolores is especially well done. It

occurs three-quarters off stage.

We wait with Walker for the news, but

all we hear are the muffled words "Africa" and

"money," accompanied by a loud laugh from Dolores

which chills us, as it must Walker. The episode is

not shown because the film, in its admiration for

Dolores, has rendered the plan absurd from the start.

Nor is the defeated Walker shown at the end of the

scene, although we hear his words, "I'm going to

bed."

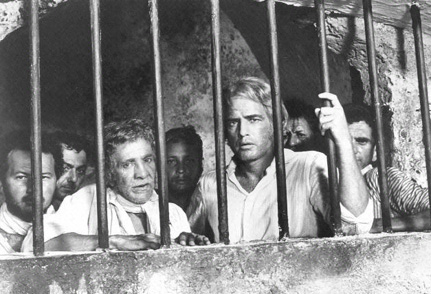

"Walker is personally

undermined by this stark contrast between

Dolores' satisfaction in moral conviction and

his own emptiness, which he only now fully

registers. The taste of victory is

bitter." |

The last interview between Walker and

Dolores is powerful. Walker desperately wishes to set

Dolores free. Dolores refuses to speak to him. The

camera focuses on the face of Brando who, having been

superseded in his superiority and moral strength by

Dolores as a mature revolutionary, cannot understand

why a man would give up his life if he has a chance

to escape. Dolores has purpose and meaning in his

life. Walker by this time has none and only now is

confronted, looking at the transformed Dolores, by

what Pontecorvo has called "his own emptiness."

Pontecorvo has described the shooting

of this scene with great poignancy:

" Walker is desperate when Dolores

refuses. He sees his own emptiness before his eyes.

And we stopped one day for this scene because

Brando was afraid. It may appear very strange, but

Brando, because of his sensibility, after years and

years of sets, after years and years of success, is

very often afraid of difficult scenes, extremely

afraid. And he is tense and nervous when he is in

such a situation. In this situation he was not able

to function. The dialogue was originally longer...

we cut out all the dialogue and I told someone to

buy Cantata 156 of Bach because I knew that it

gives the exact movement of this scene. And I cut

all the dialogue. Without saying anything to

Brando, I said, we will shoot now, we have waited

too long, we will try to shoot. I put the music on

at the moment when I wanted him to open his arms

and express his sense of emptiness. I put on the

music without telling him. I said only, "Don't say

the last part of the dialogue." He agreed. He was

happy to do this; he said it was stupid to use too

much dialogue. From this moment he was so moved by

the music that he did the scene in a marvellous

way. When he finished the scene, the whole crew

applauded. It was more effective there than on the

screen later. The sudden tension we obtained was

surprising. And Brando said this was the first time

he had seen two pages of dialogue replaced by

music."

Pontecorvo zooms to Walker as he

listens to Dolores' final message which breaks his

silence: "Ingles, remember what you said.

Civilization belongs to whites. But what

civilization? Until when?"

The stabbing of Walker on his way to

the ship by an angry rebel comes simultaneously with

a repetition of the Algerian cry for freedom. It is

followed, accompanied by percussion, by a pan of

inscrutable, angry black faces on the dock. The frame

freezes, fixing their expressions indelibly in our

minds.

The music of the end is a religious

choral piece. Played over the final moments of life

remaining to Walker who lies in the dust, it becomes

at once an apotheosis, very moving and romantic, as

it heralds in victory the fall of the tormentor. The

feeling left with the audience is simultaneously one

of horror and vindication, although the actual murder

of Walker occurs long after his moral demise.

Far more than Algiers, with its virtual equation of

the vast violence committed by the French with that

of the Algerians, Burn! was a courageous film for

Pontecorvo to make.

There are few films as passionate or

as uncompromising about the real workings and nature

of imperialism as a world order, nor a film which

identifies so feelingly with the victims of

neo-colonial rule.

Not since Eisenstein has a film so

explicitly and with such artistry sounded a paen to

the glory and moral necessity of revolution. Even

had United Artists not attempted to sabotage Burn!,

it would be a film deserving wider viewing and

critical attention.

Review- Copyright Cinema Magazine

|