|

One Hundred

Tamils of the 20th Century

V.O. Chidambaram Pillai

(VOC)

வ. உ.

சிதம்பரம்

பிள்ளை

(வ.

உ.சி)

Kappalottiya Tamilan: கப்பலோட்டிய

தமிழன்

1872 - 1936

[see also Kappal Oddiya Thamilan:

The Overseas Exploits of the Thamils & the

Tragedy of Sri Lanka]

"V.O.C. showed

the way for organized effort and sacrifice. He

finished his major political work by 1908, but

died in late 1936, the passion for freedom still

raging in his mind till the last moment. He was

known as "Chekkiluththa Chemmal" - a great man

who pulled the oil press in jail for the sake of

his people. He was an erudite scholar in Tamil, a

prolific writer, a fiery speaker a trade union

leader of unique calibre and a dauntless freedom

fighter. His life is a story of resistance,

strife, struggle, suffering and sacrifice for the

cause to which he was committed.."

[Please also see discussion

re 'what do the initials V.O.C. stand

for?]

V.O.Chidambarampillai (VOC) was born on 5

September 1872 in Ottapidaram, Tirunelveli district

of Tamil Nadu (the same District which a hundred

years earlier given birth to Veerapandiya Kattabomman).

Chidambarampillai was the eldest son of

Ulaganathan Pillai and Paramayi Ammai. His early

education was in Tuticorin. He passed a pleadership

examination in 1894 and this enabled him to

practise law at the local sub-magistrate's court.

He then went on to practise at the nearby port town

of Tuticorin.

The partition of Bengal in 1905, the rise of

militancy evidenced by Swadeshi (boycott of

foreign goods) movement, saw Chidambarampillai

taking a direct interest in the political struggle.

These were the years before the arrival of Gandhi

on the Indian political landscape.

Chidambarapillai supported Bal Gangadhar Tilak and the

militant wing of the Indian National Congress. He

participated in the 1907 Surat Congress together

with Subramania Bharati. He was

one of the earliest to start the 'Dharmasangha

Nesavuchalai' for hand-loom industry and the

'Swadeshi Stores' for the sale of India made things

to the people. He played a lead role in many

institutions, like the "National Godown," "Madras

Agro-Industrial Society Ltd.," and "The Desabimana

Sangam".

Commerce between Tuticorin and Colombo was the

monopoly of the British India Steam Navigation

Company (BISN) and its Tuticorin agents, A.

& F. Harvey.

Inspired by the Swadeshi movement, V.O.C.

mobilised the support of local merchants, and

launched the first indigenous Indian shipping

enterprise, the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company,

thus earning for himself the name - "Kappalottiya

Tamilan கப்பலோட்டிய

தமிழன்".

The Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company was

registered on the 12th of November 1906. He

purchased two steamships, S.S. Gallia and S.S.

Lawoe for the company and commenced regular

services between Tuticorin and Colombo against the

opposition of the British traders and the Imperial

Government.

His efforts to widen the base of the Swadeshi

movement, by mobilising the workers of the Coral

Mills (also managed by A. & F. Harvey) brought

him into increasing conflict with the British Raj.

On 12 March1908, he was arrested on charges of

sedition and for two days, Tirunelveli and Tuticorin witnessed unprecedented

violence, quelled only by the stationing of a

punitive police force. But newspapers had taken

note of VOC. Aurobindo Ghosh, acclaimed him in

Bande Mataram (March 27, 1908) -

"

Well Done,

Chidambaram! A true feeling of comradeship is

the salt of political life; it binds men together

and is the cement of all associated action. When

a political leader is prepared to suffer for the

sake of his followers, when a man, famous and

adored by the public, is ready to remain in jail

rather than leave his friends and fellow-workers

behind, it is a. sign that political life in

India is becoming a reality. Srijut Chidambaram

Pillai has shown throughout the Tuticorin affair

a loftiness of character, a practical energy

united with high moral idealism which show that

he is a true Nationalist. His refusal to

accept release on bail if his fellow-workers were

left behind, is one more count in the

reckoning. Nationalism is or ought to be not

merely a political creed but a religious

aspiration and a moral attitude. Its business is

to build up Indian character by educating it to

heroic self-sacrifice and magnificent ambitions,

to restore the tone of nobility which it has lost

and bring back the ideals of the ancient Aryan

gentleman. The qualities of courage, frankness,

love and justice are the stuff of which a

Nationalist should be made. All honour to

Chidambaram Pillai for having shown us the first

complete example of an Aryan reborn, and all

honour to Madras which has produced such a

man."

Apart from the Madras press, even the Amrita

Bazaar Patrika from Kolkata (Calcutta) carried

reports of his prosecution every day. Funds were

raised for his defence not only in India but also

by the Tamils in South Africa. Bharathy gave

evidence in the case which had been instituted

against him. V.O.C. was confined in the Central

Prison, Coimabtore from 9 July 1908 to 1 December

1910.

The Court imposed a sentence of two life

imprisonments (in effect 40 years). The sentence

was perhaps a reflection of the fear that the

British had for VOC and the need to contain the

rebellion and secure that others would not follow

in Chidambarampillai's footsteps.

In 1911, Tirunelveli District Collector Ashe was

assasinated by Vanchinathan, a youth trained by

V.V.S.Aiyar who had at that time had

sought refuge in French Pondicherry. The British

response was brutal and a witch hunt followed. And

the Swadeshi movement petered out with many of its

activists languishing in jail.

VOC in prison, was left to fend for himself. His

wife, Meenakshi Ammal, followed him from the

Tirunelveli sub jail to the Coimbatore and Kannur

central jails, where he spent his term and almost

single-handedly organised his appeals.

Sivaji Ganesan as VOC in

prison

in the film Kappalottiya

Thamizhan

Chidambarampillai was not treated as a

'political prisoner'. The sentence that was imposed

on him was not 'simple imprisonment'. He was

treated as a convict sentenced to life imprisonment

and required to do hard labour. He was "yoked

to the oil press like an animal and made to work it

in the cruel hot sun..." writes, historian and

Tamil scholar, R. A. Padmanabhan. Sivaji

Ganesan's portrayal of VOC in the film Kappalottiya Thamizhan

reflected that agony and that pain.

"Among the 300 films which was Sivaji's

favourite? Pat came the answer from Sivaji,

'Kappalottiya Thamizhan''. Enacting a doctor, an

engineer and others are not very difficult. But

to portray a person, a revered freedom fighter,

whom people had met, seen and moved with, is a

different proposition. So when the late Panthulu

asked me to enact the role, I first hesitated.

Then I decided to meet the challenge. I got all

the material on V. O. Chidambaram Pillai and

studied it. 'On seeing the film, I cried, not

because my performance was moving but because it

hit me with new impact - the sacrifice VOC and

others had made for the country. When VOC's son

Subramaniam said that he saw his father come

alive on the screen, I considered it the highest

award.'' Sivaji Ganesan on his Role in

Kappalottiya Tamilan

Subramania Bharati was moved to write his

வ.உ.சி.க்கு

வாழ்த்து.

வேளாளன்

சிறைபுகுந்தான்

தமிழகத்தார்

மன்னனென

மீண்டான்

என்றே

கேளாத

கதைவிரைவிற்

கேட்பாய்

நீ

வருந்தலைஎன்

கேண்மைக்கோவே!

தாளாண்மை

சிறினுகொலோ

யாம்புரிவேம்

நீஇறைக்குத்

தவங்கள்

ஆற்றி,

வேளாண்மை

நின்

துணைவர்

பெறுகெனவே

வாழ்த்துதிநீ

வாழ்தி!

வாழ்தி!

The Prison Cell that V.O.C.

occupied in Central Prison Coimbatore

"yoked to the oil press like an

animal.."

In prison VOC continued a

clandestine correspondence, maintaining a stream of

petitions going into legal niceties. When he

stepped out of prison in late December 1912, after

a high court appeal had reduced his prison

sentence, the huge crowds present on his arrest

were conspicuously absent. His feelings may have

been similar to those of Aurobindo in 1909 -

feelings which Aurobindo expressed in in

the famous Uttarpara speech, soon after his own

release from prison:

"It is I, this time who have spent one year in

seclusion, and now that I come out I find all

changed. One who always sat by my side (Tilak)

and was associated in my work is a prisoner in

Burma; another is in the north rotting in

detention... I looked around for those to whom I

had been accustomed to look for counsel and

inspiration. I did not find them. There was more

than that. When I went to jail the whole country

was alive with the cry of Bande Mataram... when I

came out of jail I listened for that cry, but

there was instead a silence. a hush had fallen on

the country and men seemed bewildered... No man

seemed to know which way to move, and from all

sides came the question, 'What shall we do next?

What is there that we can do?' I too did not know

which way to move, I too did not know what was

next to be done."

VOC was not permitted to remain in his native

Tirunelveli district and he moved to Chennai with

his wife and two young sons. Having been convicted

for sedition, he had lost his pleadership status

and he was unable to earn his livelihood by

practising the law. The Swadeshi Steam Navigation

Company had collapsed. It was liquidated in 1911.

He and his family had lost all their wealth and

property in his legal defence.

After his release in 1912 he completed his

autobiography which he had started writing in

prison. It was in Tamil in a verse form. He wrote a

commentary on Thirukural and edited the Tamil work

of grammar, Tolkappiam. He authored a few novels

in Tamil. His translation of some of James Allen's books earned

him an indisputable reputation of being an erudite

Tamil scholar. His Tamil works like "Meyyaram" and

"Meyyarivu" reflect a creative mind, restless for

uninhibited expression. V.O.C. attended the

Calcutta Congress in 1920.V.O.C. showed the way for

organized effort and sacrifice. Today when anybody

utters the name of VOC, immediately comes to mind

is his achievement as the first Indian to launch a

ship service.

"The moment anybody

utters the name of VOC, immediately comes to mind

is his achievement as the first Indian to launch

a ship service between Tuticorin and Colombo

through Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company in the

interest of the Nation's economy, and that too,

against the British Rule. His main aim was to

serve the country for attaining Independence from

the British and he had all the leadership

qualities in him that require achieving things in

macro level. He gained the patronage from leading

merchants and industrialists in Tirunelveli for

establishing a Swadeshi Merchant Shipping

Organization, which was unveiled on 16th October

1906. From then on, the company developed from

strength to strength and laid its name strongly

in the minds of everyone in Indian and foreign

countries as well." Chennai School of

Ship Management

"The nation will always remember V. O.

Chidambaram Pillai, whose 130th birth anniversary

was on 5 September 2001, principally for the

pioneering role he played in building India's

swadeshi shipping industry." VOC - the Doyen of Swadeshi

Shipping - S.Dorairaj, 2001

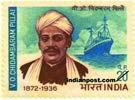

On the 5th September, 1972, on the occasion of

VOC's birth centenary the

Indian Posts & Telegraphs department issued a

special postage stamp. The citation read

"...His courage and determination to run

the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company against the

stern opposition of the British traders and the

Imperial Governmentwon the proud acclaim of one

and all..." "...His courage and determination to run

the Swadeshi Steam Navigation Company against the

stern opposition of the British traders and the

Imperial Governmentwon the proud acclaim of one

and all..."

VOC finished his major political work by 1908,

but died in late 1936, the passion for freedom

still raging in his mind till the last moment.

He was known as

"Chekkiluththa Chemmal" - a great man who pulled

the oil press in jail for the sake of his people.

He was an erudite scholar in Tamil, a prolific

writer, a fiery speaker a trade union leader of

unique calibre and a dauntless freedom fighter. His

life is a story of resistance, strife, struggle,

suffering and sacrifice for the cause to which he

was committed. In accordance with his wishes, VOC

was taken to the Congress Office at Tuticorin,

where he died on the 18th November, 1936.

.A.

R. Venkatachalapathy in the Hindu 26 January

2003 .A.

R. Venkatachalapathy in the Hindu 26 January

2003

on the Exchange of Letters between V.O.

Chidambaram Pillai and M.K.Gandhi

Between

the middle of 1915 and early 1916, Gandhi exchanged

a series of letters with a personality whose name

does not occur even once in the 100-volume

Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. The person in

question is V.O. Chidambaram Pillai (or VOC), who

between 1906-08 during the Swadeshi movement,

dominated the national movement in Tamil Nadu.

Gandhi was not yet the Mahatma then. Fresh from

decades-long political activity in South Africa,

Gandhi was still finding his feet, politically. He

had arrived in Chennai on April 17, 1915, along

with his wife, Kasturba. The couple stayed at 60,

Thambu Chetty Street (George Town), the residence

of G.A. Natesan, the nationalist publisher. He was

to stay in Chennai (Madras) for three weeks before

setting out for Ahmedabad on May 8....

.... A correspondence which began at this

juncture between VOC and Gandhi continued for about

six months, which is our present concern. We do not

know what happened to the enormous mail Gandhi

received. But VOC seems to have preserved all these

letters, and for good measure, had written his

draft replies on Gandhi's letters. So we have his

side too. The lines he had scribbled out in his

draft letters add to our knowledge - amply

rewarding for the task of decipherment.

The first letter, drafted probably a day after

Gandhi arrived, addressed Gandhi as "Dear Brother":

"I have had the fortune of seeing you and my

respected Mrs Gandhi when you came out of the

Railway compound the other evening", it said and

added, "I want to have a private interview with you

at any time convenient to you before you leave this

place". Gandhi replied promptly with a single line

on April 20, 1915: "If you kindly call at ... 6

A.M. next Friday, I could give you a few

minutes".

Switching over to a more formal "Dear Sir", VOC

replied the next day: Underlining the words "a few

minutes", he said, "As I am afraid that my

conversation with you will take more than the

allotted `a few minutes', I need not trouble you

with my presence". He excused himself "for having

intruded upon your precious time".

It was now Gandhi's turn to take mild offence:

"If you do not want to see me I would like to see

you myself. Will you kindly call on Friday or

Saturday at 6 A.M. and [sic?] give me a few

minutes?" He then went on to explain: "Of course

you can call any day between 3 p.m. and 4 p.m. when

I am open to be seen by anybody. But as you wanted

a private interview I suggested Friday morning as I

suggest some morning or the other for private

interviews". (April 21, 1915)

Here came the first poignant moment in the

exchange. VOC agreed to meet Gandhi early in the

morning but said, "I cannot reach your place before

6:30 a.m." Reason: "the tram car, the only vehicle

by which I can now afford to go to your place,

leaves Mylapore after 5:30 in the morning". A man

who had bought up two steamships a few years

earlier was now unable to take anything more than a

tram! Yet VOC went on to add, "I can spend not `a

few minutes' but, the whole of my lifetime with the

patriots of my country if they wish me to do so.

All my time is intended for the services of my

country and of its patriots. Only after these two,

God is attended to by me".

Gandhi and VOC did indeed meet. But whether VOC

took only a tram or whether they met only for "a

few minutes" we will never know. But the

correspondence did not end here. It followed the

issue Gandhi himself raised in his letter of April

21, 1915.

"I would like to know from you whether you

received some moneys from me which were collected

on your behalf some years ago in South Africa. I

was trying to trace some orders which I had

thought were sent, but I did not find them. I

therefore would like to know from you whether you

received the moneys that were handed to me."

VOC replied (April 22, 1915) that neither he nor

his wife had received any money. The reference to

his wife and the indication by Gandhi to money

collected "some years ago" suggest that it may have

had to do with the fund raised in South Africa for

VOC's defence.

(In two waves of migration from India, 1860-1866

and 1874-1911, Tamils had reached South Africa most

often as indentured labourers. Even in 1980, Tamils

constituted 37 per cent of the population, the

largest group among people of Indian origin. (A

collection of Bharati's poems, "Matha

Manivachagam", had been published in Durban in

1914. Gandhi's links with this segment of the

diaspora needs no recounting.) However, despite his

impecunious situation, he reassured Gandhi: "But,

if you will pardon me, I will say that you need not

trouble yourself ... for I am sure that it would

have gone to a better purpose".

Gandhi would of course have none of it. "I don't

know the names of those who subscribed for you but

the money was given to me by a friend on their

behalf and I have been always under the impression

that it was sent to you".

Now comes the most poignant letter. VOC replied

saying that he had presumed from Gandhi's earlier

letter that the fund had been spent towards Passive

Resistance in South Africa and, therefore, he had

asked him not to bother to remit the money

especially if it was to be from his funds. But now

that Gandhi had made it clear that it was not

so:

"I will, in my present condition, be only glad

to receive that money ... I have already told you

in person that my family and I are supported for

the past two years or so by some South African

Indians ... Such being the case, there is no reason

why I should say that the money intended for me and

that is ready to be given to me is not wanted by

me. Under the present circumstances if I refuse

that amount I will be committing a wrong to myself

and my family".

Now that the issue was settled - that Gandhi

indeed owed money, and VOC was not averse to

receiving it - a series of letters were exchanged

from late May 1915 until January 1916. To VOC's

apparently long letters, Gandhi replied on cryptic

post cards.

On May 28, 1915 Gandhi assured VOC: "I shall now

send for the book subscribed in Natal. I don't know

the amount nor the names. But I hope to get them".

VOC seems to have been in desperate need of money.

"Don't you know at least approximately the total

amount given to you by your friend? If you know it,

can you not send me that amount or a major portion

of it now, so that it may be useful to me in my

present difficult circumstances? The remainder you

may send to me after you get the books", VOC

pleaded (May 31, 1915). He also asked for the names

of benefactors. In letter after letter he asked for

these details.

It is understandable, given VOC's penchant for

remembering benefactors by naming his children for

them: Vedavalli was named for T. Vedia Pillai who

supported him and Subramaniam for C.K. Subramania

Mudaliar, who helped him during his prosecution.

Even the Englishman E.H. Wallace, who first

committed his case to the session's court but was

instrumental in getting his sanad back, was

remembered in the name of his last son,

Wallacewaran!

But Gandhi would only say, "If you will kindly

wait a while, you will have both the money and the

particulars. If I knew the name of the friend, I

should certainly let you know", and asked VOC to

write to Mr. Patak at Johannesburg for more

details.

Probably to another reminder from VOC, asking if

he had heard from South Africa, Gandhi wrote a

rather curt "Not yet, yours M.K. Gandhi" without

even a formal word of address (July 23, 1915). But

within a month, most certainly to another reminder

from VOC, Gandhi wrote with his own hand, in Tamil,

saying he had not yet heard from South Africa.

(This particular post card is in tatters.)

Gandhi writing in Tamil seems to have completely

floored VOC. Dropping the question of money VOC

started off right away, "Your card written in Tamil

reached me on the due date. I am glad to see that

you have written the language without any mistake

whatever. If you are able to read and understand

Tamil prose and poetical works of ordinary style, I

will be glad to send you all my publications"

(September 28, 1915).

However, even in December 1915 and January 1916,

Gandhi was only writing one-line letters like "I am

still awaiting instructions from Natal" to VOC's

increasingly desperate and beseeching letters.

VOC's ordeal came to an end at last when, on

January 20, 1916, Gandhi wrote from Ahmedabad, "I

have now heard from Natal", and that Rs. 347-12-0

was to be remitted to him soon.

The correspondence ends here. VOC was no doubt

relieved and delighted. On February 4, 1916, he

wrote to a friend, in Tamil, "Rs. 347-12-0 has come

from Sriman Gandhi. I have given Rs. 100 to the

pressman for casting new types. With the remaining

money I have settled all my debts except one of

Rs.50. I will need further money only to buy

paper".

Of course, VOC had heaved a sigh of relief too

early. Never really recovering from the penury

caused by his prison life - he tried his hand at

selling provisions, worked as a clerk in Coimbatore

and for a few years after regaining his pleadership

sanad, practised in the Kovilpatti court which by

his own admission was only enough to meet his

"betel leaves and areca nut expenses". This however

did not come much in the way of his public life. As

a die-hard supporter of Tilak, he could never

countenance Gandhi's leadership. Yet, until his

death in 1936, he continued to be active in the

labour movement, the national movement and the non

Brahmin movement. That, however, is a different

story.

Kappalottiya Tamilan - The

Film

Kappalottiya Tamilan - The

Film

A movie review by Balaji

Balasubramaniam

Cast: Sivaji Ganesan, Gemini Ganesan,

Savitri, S.V.Subbaiya, Rangarao, Asokan, Balaji -

Direction: B.R.Bandulu

Actors rarely identify any one of their movies as

their favorite, instead detouring around the

delicate question by saying that all the movies

they acted in had their strengths. Considering the

sheer number of movies he has acted in, picking a

favorite had to be an even tougher task for

'Sivaji' Ganesan than for most actors. But he had

repeatedly declared Kappalottiya Thamizhan to be

his favorite, stating the difficulty of playing a

famous leader, the research that went into the

movie and its realism as his reasons.

The movie effectively portrays the hardships

undergone by V.O.Chidambaram Pillai, who was

responsible for launching the first Indian ship on

Indian waters.

V.O.Chidambaram Pillai (Sivaji) is a lawyer and

also the owner of a large salt factory. He is a

true patriot, leading the movement to burn all

foreign goods. Noticing that there was no Indian

ship plying in the Indian waters, he collects the

money needed to buy a ship and launches the ship.

He, along with Subramaniam Siva, is arrested for

leading a strike of workers at a mill run by the

English and suffers untold hardship in prison.

Sivaji brings Chidambaram Pillai before our eyes

with his portrayal of the freedom fighter. He is

majestic during the initial portions, as he strides

with confidence, collecting money for buying the

ship and sure of its success in propagating the

freedom movement. He delivers his dialogs

forcefully and with passion and the accompanying

expressions and gestures complement the effect (the

single shot when the collector imagines Sivaji as

Veera Pandiya Katta Bomman is quite exhilarating).

The makeup is flawless in his old age and his slow,

uncertain walk and sad face leave us with little

doubt that we are actually seeing an old man on

screen. It is an underplayed performance but

grandiose nevertheless.

The movie effectively shows us the hardships

undergone by the people in order to gain

independence and makes us admire the patriotic

fervor in the few characters it focusses on.

Chidambaram Pillai's selfless acts are ofcourse the

highlight and the way he sells his business or his

wife's jewels without a moment's thought speaks of

his greatness. There is passion in his voice as he

dreams of an Indian ship. His wealthy lifestyle

makes the hardships he undergoes in jail even more

tragic. The scenes in jail have been picturised

well with even one of the convicts making an

impression with his respect for V.O.C.

But the movie does not focus on him solely with

the effect of making the other characters

insignificant. Bharatiyar's eccentricity and

Subramaniam Siva's forcefulness are well brought

out during their segments. Ofcourse these

characters have their best scenes when seen with

VOC. Subramaniam Siva has his best lines during his

visit to the Collector's office with VOC while

Bharatiyar shines when asked about his association

with VOC in court. Individuals like Gemini

Ganesan's Madasami get substantial screen time and

Vanchinathan manages to impress us in the little

time he is on screen.

Maybe because VOC could not accomplish much

after he came out of jail or because there are no

records of that segment of his life, the portions

of the movie dealing with that part seem rather

rushed. His transformation to an aged man seems

abrupt with only newspaper reports about the death

of his fellow freedom fighters being used to

indicate the passing of time. The last scene is

suitably touching with Bharatiyar's Endru

Thaniyum....

S.V.Subbaiya is perfect as Bharatiyar and his

expressions, gestures and dialog delivery are

superb. Among all the actors who have portrayed the

poet in cinema, no one comes as close as

S.V.Subbaiya. Gemini Ganesan and Savitri have a few

cute lines as the lovebirds. S.V.Rangarao, who

usually plays a benevolent old man, appears as the

British collector here. Asokan too has a role as

the assistant collector. Songs like Velli

Paniyin... and Vande Maataram... are very

memorable.

|