|

One Hundred

Tamils of the 20th Century

Sivaji Ganesan - Nadigar

Thilakam

1 October 1928 - 21 July 2001

Sivaji Statute in Marina,

Chennai unveiled on 21 July 2006

Parasakthi - Sivaji Ganesan's

First Film, 1952

A Lesson in Gratitude from

the Movie Maestro Sivaji Ganesan

by

Sachi Sri Kantha, 20 December

2005...

It is always enchanting and

heart-warming to read and listen to real life

events, which are educational at any time to

individuals of all age ranges.

In this spirit, towards the end of

the year, I provide the following two anecdotes

from the life of Tamil movie legend, Sivaji Ganesan

(1928-2001). In these two anecdotes, Sivaji Ganesan

had taught to many, what is gratitude and why it

deserves recognition and popularisation.

The first anecdote was from a

memoir book about the Tamil movie world which I

read recently, It was authored by distinguished

Tamil movie script writer Aroordhas, who had known

personally and professionally Sivaji Ganesan for

decades.

The second anecdote was oral

history I heard in Colombo three decades ago from

one of my music mentors,violinist Vannai

G.Shanmuganantham.

Both anecdotes have a few

inter-linking threads. The oral story I heard

around 1975 neatly gelled with the written story

which I read recently.

Sivaji Ganesan and his tutor

K.D.Santhanam [written story]

Sivaji with

Aroordhas |

Renowned script writer and director

Aroordhas (born 1931) has a five decade track

record in Tamil movie history. His stage name

Aroordhas is a clipped version of his full village

cum personal name of Tiruvaroor Aarokiyadhas. His

memoir book, Naan Muham Paartha Cinema Kannadigal

[The Cinema Mirrors I have Looked At; Kalaignan

Publishers, Chennai, 2002, 224 pages] carries a

delightful collection of anecdotes on the

personalities who moved the movie world of South

India. I was rather touched by a reminiscence

provided by Aroordhas on Sivaji Ganesan in section

18 of the book (pages 109-113). I provide my

English translation of this entire section

below.

�The Madurai

Mangala Bala Gaana Sabha was a drama troupe managed

by Ethaartham Ponnusami Pillai of Thiruvathavoor,

Madurai. This troupe stationed themselves in

Tiruchi and conducted dramas at the Thevar

Hall.

From Sangili Aanda Puram, a boy

aged 6 or 7 had joined this drama troupe with his

friend, a neighbor�s son. In this

drama troupe, there was a Tamil tutor (Vaathiaar)

who taught drama and Tamil to the young charges. He

was short in stature and was extremely strict. With

or without sense, this tutor punished his young

charges by cane beating, even for smallest errors.

Because of this, the young boys had their bowel

leaks, when they saw or even dreamt about this

extreme disciplinarian cum tutor. In their dreams,

he appeared like a charging lion.

But that Tamil tutor had a great

gift. He could compose beautiful, rhyming Tamil

songs based on poetic grammar. One day, at the

stage, that boy from Sangili Aanda Puram was acting

in the role of a young widow. And by carelessness

on that day, he was wearing a blouse. This had been

noticed by that disciplinatrian tutor.

In that era, wearing blouse by

widows was rather inappropriate according to

societal norms. At the end of the scene, that Tamil

tutor harshly gave a cane beating to that young

boy; �Can�t you

be so careless and unrealistic in your

profession?� was the complaint

against that young boy.

Guess who was that young charge,

who received such a beating? Maestro Sivaji

Ganesan. Who was that cane-loving tutor? My most

respectful and admired elder and great poet,

K.D.Santhanam (S).

43 years ago, during the shooting

of the movie �Pasa

Malar�, I met elder K.D.S. at the

old Neptune Studio and paid my respects. In that

movie, when Sivaji Ganesan (the hero) becomes rich,

he is met by a character named

�Rajaratnam�.

KD.Santhanam played that character.

That young charge V.C.Ganesan never

forgot about, in his illustrious career, from whom

he received the cane-beating and from whose beating

he learnt the alphabets of acting and Tamil

diction. It was he, after establishing his fame in

the movie world, who recommended his harsh

disciplinarian tutor for that particular character

in his great movie.

During the shooting days, Sivaji

would be seated outdoors near the shooting floor

with crossed legs and be in conversation with me,

while having a cigarette in his lips. Then, elder

K.D.Santhanam would occasionally pass us from the

make-up room towards the shooting floor. At the

instant when Sivaji sees his old tutor, he would

dutifully stand up in respect, and hide the

cigarette behind his back. Though noticing that

homage silently, the old tutor K.D.S. pretend

ignoring us and with bowed head pass us

quietly.

It would touch my heart, when

watching that simple, elegant and meaningful

respect Sivaji paid for his old tutor. What a

class! What a grateful

prot�g�! I

mention this anecdote because the younger

generation should be informed of this humility and

gratitude shown by maestro Sivaji.

Once, after K.D.S. had passed us

and went beyond the listening distance, Sivaji sat

back and told me: �Aarooran! On

this Santhanam tutor (Santhana Vaathi) who passed

us. The amount of beating I got from him

isn�t a few. During dance training

(when a step is missed for a beat), during dialogue

training (when a word is missed), he beat us

severely! Oh Mother �

He�d chase and chase us and beat

us! Even when he went to the toilet, he carried his

cane. Now he is passing us like a young girl with

head turned towards the floor. Even when I thought

about him in those days, I�d

shiver.�

I asked him jokingly:

�Then, why did you recommend him

for this role?�

[Sivaji said] �You

don�t know. Because of those

beatings I received from his hand,

I�m now sitting comfortably like

this as Sivaji Ganesan. When I joined the drama

troupe, I was a zero. From him only, I learnt how

to speak dialogue and how to act. Do you know, what

a classy Tamil poet he is? What a poetic touch he

carried in his hands? The songs he wrote for the

Ambikapathi [1957] movie I acted: Ah! What sweet

Tamil, and what lilting rhythm! I tolerated all

those beatings because of his blessed Tamil

knowledge. Otherwise, I�d have

quit the troupe and ran back to my home during any

one of those nights.�

Later, when elder K.D.S. was alone

at the shooting floor, I approached him and

politely mused;

�Elder Sir,

I�ve heard that you gave severe

beating to Sivaji Annan in his young

days.�

[K.D.S.] �Oh! He

has told you about that. Oh! That was in those

days. Now I�m becoming senile. I

cannot remember your script now. Not only that,

when Thambi Ganesan stand in front of me,

shouldn�t I look at his face and

deliver my dialogue? When I look at him now,

I�m getting nervous! Because of

that, can you prepare me for my dialogue by

repeating your script not once but four times? It

may be a bother. Kindly

oblige.�

How Time did change? The same great

tutor who taught dialogue to Sivaji Ganesan in his

young days, with disciplinary cane at his hand, now

he feels nervous to stand in front of his

illustrious

prot�g�, and ask

me to prepare him well for a scene in which he

faces his

prot�g�.�

When I read these pages from

Aroordhas�s book, I was touched by

three inter-twined elements;

(1) a thankful

prot�g�s devotion

to an extremely strict, but sincere, mentor,

(2) repayment of intellectual debt

by an esteemed

prot�g�, and

(3) the mentor�s

heart-felt pride on the grade made by his

prot�g�.

What Sivaji Ganesan said of the

touching poetic feel of his mentor K.D.Santhanam

was no exaggeration. The 16 lines of that one sweet

melody in the Ambikapathi [a historical love yarn

set in the 12th century Chola Kingdom, along the

lines of the more popular Romeo-Juliet story]

movie, beginning with the lines

�Kannile Iruppathenna Kanni Ila

Maane� and sung by P.Bhanumathi as

well as T.M.Soundararajan were from the fertile

mind of K.D.Santhanam.

Sivaji Ganesan and his boyhood

pal E.Subbiah

Pillai [oral story]

Around the time [in 1961 or 1962]

when his signature movie Pasa Malar was released,

Sivaji Ganesan visited Colombo. I heard the

following story from my mentor Vannai

G.Shanmuganantham, around 1975, who was an

eye-witness.

E.Subbiah

Pillai |

At a cultural function held at the

Saraswathie Hall, Bambalapitiya, Sivaji Ganesan was

the guest of honor. With his roving eye, he had a

glance at the orchestra performing at the side of

the stage. During intermission, he rushed to the

orchestra team and stood in front of the

clarinetist E.Subbiah Pillai, who was calm and

composed. With stretched hands, Sivaji greeted him,

�Neenga Subbiah Annan

ille� [Aren�t you

Subbiah elder?]. The clarinetist softly responded

in the affirmative. Then, Sivaji immediately hugged

his long-lost boyhood pal, and was overcome with

emotion. The words fumbled from his mouth.

�Anne! Suhama

irukeengala? Eppavo, Ceylonukku oodi poonatha

sonnanga. Athukappuram, oru sethiyum

kiddaikale.� [Brother, are you

keeping fine? Those days, I heard that you have run

to Ceylon. After that, I didn�t

hear any news about you.]

Then only it became known to the

fellow members of that orchestra team that Sivaji

Ganesan [a junior] and Subbiah Pillai [a senior]

were boyhood pals in a boys drama troupe, and one

day [partly because of the disciplinary tactics of

their tutors and partly because of the lure

provided by a sea-crossing trip to Ceylon], Subbiah

Pillai had moved to Ceylon without announcing his

decision to his then clique. Thus, the pals became

separated.

In the intervening 25 years or so,

while Sivaji Ganesan became a famous movie star in

Chennai, Subbiah Pillai established himself as a

clarinetist in the Radio Ceylon artiste. Subbiah

Pillai, as a senior to Sivaji Ganesan, might have

taught a few

�steps� in the

art world then, to the talented rookie. Sivaji

never forgot the face of his senior.

I personally knew Subbiah Pillai

�Master� in the

late 1960s and early 1970s. In fact, for my flute

debut performance [Arangetram] held on December 3,

1971, at the Bambalapitiya Sammangodu Vinayagar

Temple, my mentor T.P.Jesudas honored him by

requesting him to �keep the Talam

[rhythm keeper]� in front of

me.

Then, after I entered the

university, due to demands on time, I lost much

contact with those older generation of musicians.

One day [before I heard this Sivaji Ganesan

anecdote from violinist Shanmuganantham Master] I

received the news with shock that Subbiah Pillai

�Master� had died

in Jaffna hospital, following a medical misa

dve200re a00er an operation. Even now, I get a lump

in my throat when I think about the calm and

composed Subbiah Pillai Master � a

senior to Sivaji Ganesean of old drama troupe days

- who was the only clarinetist I knew in Colombo in

those days.

|

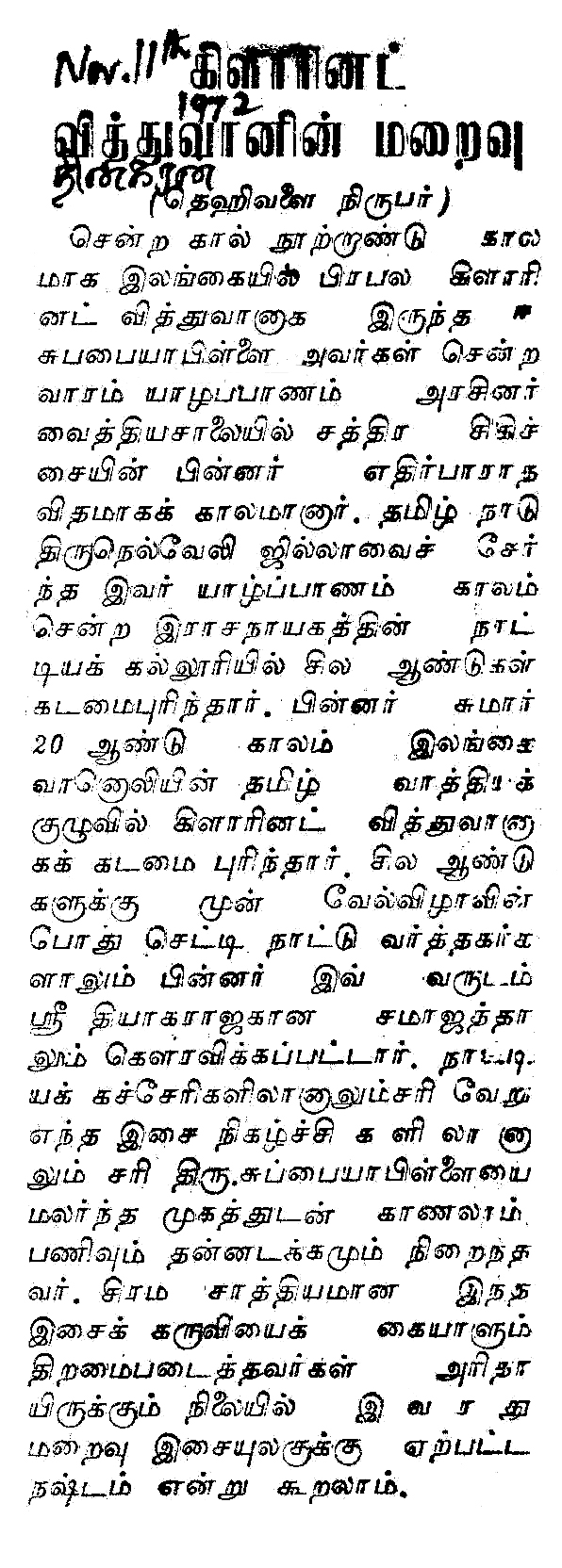

...from Sri Lanka Tamil Daily

'Thinakaran',

11 November 1972 - on Death of Subbiah

Pillai

|

|

Sivaji Ganesan: Autobiography of An

Actor. Compiled and edited by T.S.Narayana

Swamy (in Tamil), English translation by Sabita

Radhakrishna; Sivaji Prabhu Charities Trust,

Chennai, 2007, 250 pp. Book Review by Sachi Sri Kantha, 11 November

2008

Sivaji Ganesan: Autobiography of An

Actor. Compiled and edited by T.S.Narayana

Swamy (in Tamil), English translation by Sabita

Radhakrishna; Sivaji Prabhu Charities Trust,

Chennai, 2007, 250 pp. Book Review by Sachi Sri Kantha, 11 November

2008

Brando and

Ganesan

Marlon Brando (1924-2004) in

USA and Sivaji Ganesan (1928-2001) in South India

were talented contemporaries. Both set the

definitions for what acting is, both in stage and

in movies in their cultural milieu. Both were

school drop outs; while Brando left school during

his high school years, Sivaji Ganesan never even

completed his primary schooling. Both blossomed as

talent that has been unseen and unheard of; Brando

in the hands of Elia Kazan, and Sivaji in

delivering the scripts of Anna and Karunanidhi. In

late career, both had their critics; Brando was

lampooned for his �method

acting� and Sivaji was critiqued

for his

�overacting�. One

day in 1962, both Brando and Ganesan met for lunch

and exchanged pleasantries in Hollywood.

The motif of a new face seizing

an opportunity of a life time when the chosen star

rejects the role in stage or cinema is a recurrent

theme. In his autobiography, Marlon Brando noted

that his big break in stage in 1947, for a

Tennessee Williams play, A Streetcar Named

Desire, came when he was the third choice as

the lead male cast. Two established movie stars,

first John Garfield (1913-1952) and then Burt

Lancaster (1913-1994) had to turn down the role.

Then, the director and producer of the play felt

that he was �probably too

young�, but left the final

decision of selection to playwright Tennessee

Williams, who wanted Brando to

�have the role�.

A Streetcar Named Desire play opened in New

York on Dec.3, 1947 and a 23 year old Brando became

the talk of the town.

Akin to

Brando�s story, we have Sivaji

Ganesan, hailed as the Marlon Brando of Indian

stage and screen, who seized an opportunity of his

life time in 1946, at the age of 18, when he was

offered the role of Maratha king Sivaji, for a play

authored by C.N.Annadurai (Anna) �

a role that was rejected by M.G. Ramachandran

(MGR), at the last moment. Here are excerpts from

Ganesan�s reminiscences of his

lucky break:

�Anna wrote

the play Sivaji kanda Hindu Rajyam.

Originally, M.G. Ramachandran was chosen to play

the role of Sivaji and the costumes tailored for

him. For some reason MGR turned down the offer.

With hardly a week left for the play, D.V.

Narayanaswamy, the stage manager, was extremely

worried. He told Anna that MGR had refused to act

this role. Both had a brainstorming session to

find alternatives�Anna thought a

beard would look good on me. He put the question

to me very directly. �Ganesa,

are you willing to act as

Sivaji?� I perspired profusely

at this question�Anna asked me

to try it out. Moreover he had the confidence

that I could do it. He handed me a 90 page

dialogue manuscript and advised me to go through

it. He was going home and on his return would

audition me for the role. Anna gave me the

manuscript at eleven in the morning and he came

back around six in the evening�I

managed to memorise so much in merely seven

hours. �You are

Sivaji�, he announced, his voice

choking with emotion. If I could memorise a 90

page manuscript in a relatively short time, it

was only because of my passion for acting, you

could even call it

addiction�There were only four

days left for the play to be staged and all the

costumes tailored for MGR had to be downsized to

suit me. They had to pad cotton in some places to

correct the size difference as I was a mere boy

and was slightly built at that

time.�

Thus, at the age of 18, Ganesan

received his moniker

�Sivaji� in 1946,

and comfortably carried it to this tomb.

�I am not very sure of the day of

the week, but I know I was born on October 1,

1928.� said he. That day was a

Monday, and on that day his father Chinnaiya

mandrayar was arrested for taking part in an

anti-British campaign in Villupuram. This

autobiography of Villupuram Chinnaiya Ganesa

Moorthy (Ganesa Moorthy was his original name)

first appeared in Tamil on Oct.1, 2002, on the

first posthumous birthday of Sivaji. It consists of

a question and answer format. The questions were

formulated by Dr. T.S. Narayana Swamy, and Sivaji

provides reminiscences of his notable life. The

English version appeared five years later on Oct.1,

2007.

For a comparison on the

influence of maternal love, here is

Brando�s reminiscences:

�The money that came with A

Streetcar Named Desire was less important to

me, however, than something else: every night after

the performance, there would be seven or eight

girls waiting in my dressing room. I looked them

over and choose one for the night. For a twenty

four year old who was eager to follow his penis

wherever it could go, it was wonderful. It was more

than that; to be able to get just about any woman I

wanted into bed was intoxicating.�

Brando was unlucky in that his mother turned out to

be an alcoholic and he suffered badly from lack of

maternal love and direction.

For Sivaji, his mother Rajamani

Ammal, though illiterate had a

mother�s common sense in directing

her prodigious son�s family life.

Ganesan reminise�s in gratitude:

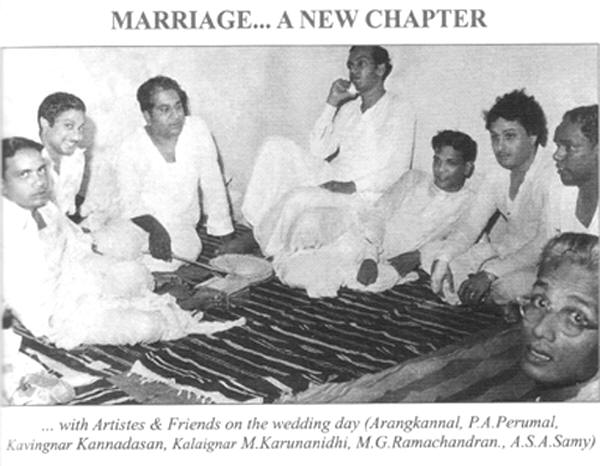

�The film Parasakti was

released in 1952 and I got married the same

year�My mother decided that it was

time for me to tie the knot and arranged to get me

married to my cousin�s daughter

Kamala�The simplicity of the

wedding made it a revolutionary ceremony. I was

married on May 1st 1952 at Swamimalai, a place

close to my cousin�s house. Sri

P.A. Perumal, annan MGR, Sri Karunanidhi, the poet

Kannadasan, Smt. T.A. Maduram, Sri. S.V.

Sahasranamam, along with directors Krishnan and

Panju attended my wedding�Nowadays

much emphasis is placed on celebrating weddings

extravagantly with glitz and glamour. My wedding

was devoid of that and my total expenditure was

only five hundred rupees! I confess that I did not

have the means to spend

more.�

For the uninitiated,

P.A.Perumal was the producer of

Sivaji�s first movie

Parasakti, who stood by his talent when

other influential personnel (like

AVM�s studio boss Meiyappa

Chettiar and director P. Neelakandan) in the

studios griped about him. Karunanidhi was the

script writer for the movie, veteran Sahasranamam

was a fellow actor in the movie and Krishnan-Panju

were the directors of Parasakti. The mention

of 500 rupees for his wedding seems to be a dig and

rebuke to the well-publicized wedding of his grand

daughter N. Sathyalakshumi to

Jeyalalitha�s then adopted son

V.N. Sudhakaran, that made news on Sept.7, 1995.

In a profession rife with

polygamy, paramours, dalliances and affairs, Sivaji

practiced monogamy and attributed his mental health

and vigor to his wife�s devotion

and love. His sincere compliments to his wife Kamal

were, �She is the captain of our

home and my boss. I will act only in accordance

with her wishes.� The book is

dedicated to Kamala, who died on Nov. 3, 2007.

Hard

Work

In the first edition (1963) of

their landmark book, Indian Film, Eric

Barnouw and his

prot�g�

S.Krishnaswamy, allocated three paragraphs to

Sivaji�s role and relevance to

Tamil movies. (Krishnaswamy was the son of K.

Subramanyam, one of the pioneers in Tamil films.)

However, in the second edition (1980) of the same

book, the three paragraphs had been condensed into

a single paragraph. For record, I provide the

first, adulatory paragraph that appeared in the

first edition below, to reflect the importance of

Sivaji the actor in the then Madras in late 1950s

and early 1960s, when his influence was at its

peak.

�In Madras

one of the most astonishing phenomena is film

star Sivaji Ganesan. Among southern film stars

only M.G. Ramachandran, the star associated with

the Dravidian movement, has in recent years come

close to him in status. For some years a leading

Madras theatre has shown only films starring

Sivaji Ganesan. This has not been difficult, for

he stars in innumerable films. For some years it

has seemed risky for any producer to produce a

Tamil film not starring Sivaji Ganesan.

[italics, as in the original.] He produces films

himself but also appears in the production of

others. He is always involved in many projects

simultaneously, dolign out a morning of shooting

time here, an afternoon there, while numerous

producers wait nervously for his next moment of

availability. It is common for films made under

these circumstances to be in production one, two

or three years, or even more. For some years in

the Madras film industry scores of film workers

� producers, directors, actors,

writers, technicians � have at

all times been dependent on the favorable

decisions of Sivaji Ganesan. His nod secures

financial backing. Because of his central

importance, script, cast and choice of director

are all subject to his approval. During his

precious appearances at the studio he works with

speed and precision, and can be so charming to

co-workers that he is adored by all. Then he is

off again, leaving anxiety as to when he will

return once more. In appearance he does not

especially conform to any hero pattern. He is, on

the contrary, squat and stockily built. But his

fine voice has a large range of expressiveness,

and he can play such a variety of roles that

almost any starring role is offered to him

� comic or tragic

� without regard to suitability.

Such is his standing, so precious his time, that

no director dares direct him, and his scenes are

often completely out of key with other portions

of a film. Seldom has a substantial talent been

used so recklessly � or so

profitably. He has amassed a fortune and carries

on well-organized and well-publicized

charities.�

Sivaji concurs with the profile

of him provided by Barnow and Krishnaswami. Before

his first invited trip to USA in 1962, he notes:

�I had signed up for the film

Bale Pandiya. I went into the studios on the

second of the month and left the sets on the

twelfth after completing the film. I probably hold

the world record of completing a film in eleven

days time. I had acted in three roles in the film

and annan M.R. Radha in two.� In

another page he had stated:

�During the period of my life when

I was extremely busy, the studios would assign

rooms exclusively for me during the different

shifts. I worked in three shifts (7am-1pm),

(2pm-9pm), (10pm-5am). I used to work twenty hours

a day, and on odd days return home for four hours

of rest. Many a time I would run through the

day�s schedule and move to the

next studio to begin the following

day�s work. I compensated for my

sleep deprivation by napping whilst traveling in

the car and during breaks.�

An Autobiography

in Three Shots

A technical dictionary defines

a shot as �what is recorded

between the time a camera starts and the time it

stops, ie., between the director�s

call for �Action�

and his call to

�Cut�. The three

common shots are, (1) A long shot or establishing

shot, showing the main object at a considerable

distance from the camera and thus presenting it in

relation to its general surroundings; (2) A medium

shot, showing the object in relation to its

immediate surroundings; (3) A close-up, showing

only the main object, or, more often, only a part

of it.

The gamut of this autobiography

consists of 155 questions and answers. Among these,

the first 49 questions provide the long shot,

covering Sivaji�s life from

childhood to the release of his first movie

Parasakti in 1952. In this, the hero

remembers with gratitude those who helped him in

kind and cash � drama troupe

leader Yathartham Ponnuswami Pillai, his senior

actors Kaka Radhakrishnan, M.R. Radha, N.S.

Krishnan, MGR, Anna, Karunanidhi, producer of his

first film P.A. Perumal and the directors of

Parasakti, Krishnan and Panju. Following 63

questions offer a medium shot, covering the period

from 1952 to 1970, when Sivaji�s

influence in the Tamil movie reached its peak. He

remembers affectionately his guru in politics, the

Congress leader K. Kamaraj, and a few in the movie

world � like producer/director

B.R.Banthulu and directors A. Bhimsingh and

A.P.Nagarajan. Final 43 questions spanning the

period from 1970 to 1993 were more or less close-up

shots, when Sivaji dabbled in politics and became a

flop. He also nursed a hurt feeling that his

contributions to the Indian movie world had been

slighted by national politics, indifference and

professional politician

�termites� (his

term), who used him for their wants.

In

Politics

Sivaji

Ganesan�s political career lacked

direction and commitment. From 1946 to 1957, he was

aligned with DMK leaders like Anna and Karunanidhi.

He says: �I have never been a

member of the DK or DMK. No doubt, I accepted the

ideologies of Anna and Priyar and tried to spread

their message. I accepted the principles for which

the party stood, but did not become a

member.� Then from 1957 until

1975, Sivaji�s mentor in politics

was Congress leader Kamaraj. After

Kamaraj�s demise, he shifted his

alliance to Indira Gandhi, until her death in 1984.

Indira Gandhi nominated Sivaji,

for the Rajya Sabha (Upper House) in 1982, after

this post became vacant following the death of

Hindi actress Nargis (1928-1981). A bout his

performance at the Rajya Sabha, Sivaji reminisces:

�If I spoke my mind just became I

was an MP, it would lead to squabble. I went to

Delhi to represent the woes of the film industry. I

attended the Rajya Sabha sittings, spoke about the

ideals of Kamaraj at opportune moments and

instigated others to follow them. What more can one

do?� After Indira

Gandhi�s assassination,

Sivaji�s ties with the Congress

Party soured, which he attribute to tale carriers

in the party who are professional politicians.

Strangely he never mention a Congress Party

big-wig�s name in Tamil Nadu (the

likes of R. Venkataraman, G. K. Moopanar, Kumari

Ananthan, V. Ramamurthi, Maragatham Chandrasekhar

and P. Chidambaram) in his recollection.

About Rajiv

Gandhi�s selection and tenure from

1984 to 1989, Sivaji�s thoughts

are as follows: �I also played a

part in making Rajiv Gandhi a politician and worked

to make him the prime minister. One should not

forget that, should one? Prior to the elections I

met Rajiv Gandhi at the Governor�s

residence. I told him rather pointedly that there

were many termites in the party and that he must

get rid of them, otherwise he could not become the

prime minister. Rajiv Gandhi�s

face reddened on such a delicate issue being

brought out in the open. Quick to seize advantage,

certain persons of our State thought that the

moment was just right to eliminate me. They passed

on some unsavoury information to Rajiv Gandhi about

me. They made me a scapegoat. I thought to myself

that I did not need this party and if I stayed,

they would humiliate me further.�

On Jan.28, 1988, Sivaji quit

his ties with Congress Party that sustained him for

over 30 years. Soon after that, he established his

own party named Tamizhaga Munnetra Munnani (TMM) on

Feb.10, 1988. He considers this decision as one of

his mistakes. �Many of the people

with me were professional politicians. They had to

remain in politics necessarily to make a living. I

was compelled to start a party for their sake,

although I did not require it.�

Egged on by those who pampered him, his TMM party

contested the January 1989 Tamil Nadu state

legislative assembly elections, in alliance with

one faction of AIADMK (that of

MGR�s wife Janaki Ramachandran).

Of the 49 TMM candidates who stood for election,

none were elected. Sivaji himself lost at

Tiruvayaru constituency to DMK candidate

Chandrasekaran Durai by a margin of 10,643 votes.

He notes, �The votes that I

secured came from people of another party. It is

true that I was defeated. This was a big

disappointment and a very difficult situation that

I faced. What could one do? When we take wrong

decisions, we have to face

disappointments.�

Later, Sivaji dissolved his

party and on invitation from his friend V.P. Singh

(later to be prime minister), he joined the Janata

Dal and functioned for a while only to quit later.

His advice to artistes with political inclinations

were: �Be a friend to politicians

but do not become a politician. Do not become a

member and get caught in the

web�Remain a singer,

don�t become the

song�this is my

message.�

Plus and

Minus

The plus points of the book

include, (a) a memorable assemblage of retrieved

old photos of stage plays and clips of movie

stills, (b) an appendix providing a listing of

Sivaji�s 10 plays, staged by his

troupe Sivaji Nadaga Mandram, 287 movie titles and

another 18 movie titles that featured him in a

guest/honorary role. A notable demerit of the book

is the absence of an index, a common omission in

Tamil books.

I located a slip in

Sivaji�s famed memory. He had

noted that on his way to USA in 1962 as a guest of

cultural exchange program, he first landed in Rome.

�I was scheduled to join His

Holiness the Pope for a meal, but unfortunately the

Pope died a week before my arrival and I did not

get the chance to meet him.� The

fact is that Pope John XXIII died not in 1962, but

on June 3, 1963.

Though he had seen three

generations of performers from age 7 to 70, Sivaji

had been diplomatic on commenting about the

performances of fellow artistes �

actors, lyricists, music directors, playback

singers, script writers and directors. His comment

was: �I am an actor and it would

not be ethical to comment on another performer. I

will only say that he or she performed well but

will never comment on anyone�s

�bad

performance�.� It

appears that he never had his likes and dislikes.

To the question �What was your

salary for the film

Parasakti?� Sivaji had

replied: �The highest salary I got

those days was 250 rupees per month. This was my

remuneration for Parasakti. I received

25,000 rupees for each of the other projects. The

250 rupees salary was an honorarium and the 25,000

for my expertise as an entertainer. As Sri P.A.

Perumal was instrumental in giving me the first

opportunity, I agreed to a small remuneration from

him.� That was in 1952. One would

be curious to learn, how much he earned for his

100th movie, Navarathri (1964),

200th movie, Trisoolam (1979) and

for his final 287th movie Pooparikka

Varukirom (1999). Information of his earning

when he was at his peak are sadly missing.

On completing the 250 page

book, one gets a feel that much has been left out

in this autobiography. May be, the question and

answer format adopted has a role in such omissions.

Proper, penetrating questions may have been omitted

for reasons of causing inconvenience for those who

are living. Sivaji�s taste on

sporting interests (wild game hunting) had been

noted. But we are left clueless about his taste for

books and authors � how big was

his library? his taste for music and movies

(actors, directors and technicians) in other

languages. Not much information was forthcoming on

the business angle of his cinematic involvement in

Tamil Nadu. A few of Sivaji

Ganesan�s professional associates

(such as MGR, Karunanidhi, poet Kannadasan,

director C.V. Sridhar and script writer Aroordhas)

have left their impressions in Tamil. Among those I

have checked, quite a few details on Sivaji

presented by Sridhar and Aroordhas in their

memoirs, are missing in this autobiography.

To sum up, as an actor Sivaji

Ganesan was a class act, as a politician he was a

flop. As an autobiographer,

Sivaji�s performance

� like many of his movies

� provides glimpses of some class

in a flop, leaving much to be desired. Eric Barnow

and Krishnaswamy, in the 2nd edition (1980) of

their book, Indian Film, summed up on

Sivaji: �He could view his own

eminence objectively. Those who sought his favour,

he said, had mixed feelings toward him. They wooed

him but would also like to destroy him. Asked if

the dominance of the star was good for the

industry, he said without hesitation that it was

not.� Ganesa Moorthy the

gentleman, when he passed away on July 21, 2001,

took to his grave the hurt feelings and the

misdeeds of those who had benefited from him and

who attempted to destroy him. The $45.00 price I

paid for the book in net purchase from a New Delhi

vendor seems marginally off-base for a 250 page

book, and the price has not been inserted in the

book. But for fans of Sivaji, it is a good memento

to cherish.

Sources Consulted

Aroordhas: Cinema

� Nijamum Nizhalum.

Arunthathi Nilaiyam, Chennai, 2001.

Aroordhas: Naan Muham

Paartha Cinema Kannadigal. Kalaignan

Pathipakam, Chennai, 2002.

S. Barnet, M. Berman,

W.Burto: A Dictionary of Literacy, Dramatic

and Cinematic Terms. Little, Brown & Co,

Boston, 1974.

E. Barnow, S.Krishnaswamy:

Indian Film. Columbia University Press,

1963 (1st edition), Oxford University Press, 1980

(2nd edition).

M. Brando: Brando

� Songs My Mother Taught Me,

1995.

S. Chandramouli: Thirumpi

Parkiren � Director Sridhar.

Arunthathi Nilaiyam, Chennai, 2002.

|